![]() TOM ARNOTT

TOM ARNOTT

![]()

Canada Goes to War

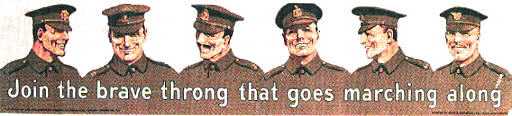

Within two days the Canadian forces were mobilizing. Sir Sam Hughes, the colourful Minister of Militia and Defence, appealed to the men of Canada, "I call for volunteers - volunteers, mark you. I have insisted that it be a purely volunteer contingent."

While the recruiting of volunteers was being improvised in the armouries and drill halls across the country, frantic efforts were begun to make a camp out of the scrub land of Valcartier, Quebec (just north of Quebec City) By early September, Canada's First Contingent comprising of 32,600 men was assembled at Valcartier. This was quite a feat, considering that in 1914 Canada's regular army numbered only 3,110. The men were organized into the 1st Canadian Division, with four Brigades and sixteen Battalions. The 2nd Canadian Infantry Battalion was one of these. Later, as the war progressed, the 2nd, 3rd and 4th Division would be added. On October 15, 1914, the 1st Division sailed into Plymouth, England, a mere 10 weeks after war was declared.

Meanwhile, the war across the English Channel had taken a very different turn. The German advance into France was stopped in mid September (1914) but the British and French attempts to push them back or outflank them failed. By mid-October, the opposing armies had dug continuous lines of trenches, that extended from the North Sea coast of Belgium, all the way to the Swiss border. And these lines of trenches-dug ever deeper, expanded by the addition of successive lines of entrenchments and increasingly protected by thick entanglements of barbed wire-remained the front lines (The Western Front) for much of the next four years. On October 12, 1914, the first battle was fought near Ypres, Belgium, (The First Battle of Ypres) in an area that became known as the Ypres Salient, because of the 'bulge' of the British front lines into the Germans'. This area of Flanders, Belgium, would become all to familiar to the Canadians over the next three years.

On February 15, 1915 the 1st Division landed in France (after spending 4 months in England) and by March the 3rd they were made responsible for a 6000 metre section of the front at Fleurbaix, France. By April, they were ordered northward to Ypres, Belgium. It was here on April 22nd, the Germans first used chlorine gas on the French Colonials' (Algerian) position which formed the Canadian 1st Division's left side (flank). The French Colonials fled, leaving a 7km gap in the Allies front line. The Canadians, who bore the brunt of the attack, along with British units (the allies were outnumbered by as much as 6 to 1), attempted to repel the 3 German Divisions that were advancing into the non-existent defences. In the ensuing battle, the Canadian 15th Battalion was gassed. The Germans pushed into the Canadians' left flank causing high casualties and a good number of Canadians were captured. After a tenaciously fought 3-day battle, the Canadians were finally able to stop the advance.

The Second Battle of Ypres was the 1st Division baptism of fire, very much one of the 'great' battles in the history of the Canadian Army. However, 1800 were killed and 4900 wounded (60% of their numbers). It was fought by very inexperienced, yet brave men, men who never shrank from duty or great personal danger, men who showed remarkable initiative when it was needed and perhaps more importantly, men who cared greatly for their battalion brothers. The British High Command felt that if the Canadians had not fought so bravely, the war may have eventually been lost. This set a heroic standard the Canadians would follow for the rest of the war. The Canadians had proven they could hold their own against a well respected enemy.

| Of an interested note it was at The Second Battle Of Ypres, that Major John McCrae of Guelph, Ontario, wrote the poem, "In Flanders Fields". McCrae was a doctor with Canadian Army Medical Corps, who tended to hundreds of wounded every day and was surrounded by the dead and the dying. The day before he wrote his famous poem, one of McCrae's close friends, Lieut. Alexis Helmer, was killed. In the absence of a chaplain, McCrae performed the funeral service. Helmer was buried in a small cemetery just outside of McCrae's aid station.. Wild poppies were already beginning to bloom between the crosses marking the graves. He wrote the poem in about fifteen minutes while sitting on the steps of an ambulance overlooking the graves. |

McCrae would later die, on January 28, 1917, of pneumonia and meningitis. He is buried in the Wimereux Communal Cemetery, just north of Boulogne, France, not far from the fields of Flanders.

The Canadian forces would participate in almost every major allied military operation on the Western Front from 1915 until 1918. Of particular note was The Battle of Vimy Ridge, April 9-12, 1917 and the Battle of Passchendaele, October 29-November 10,1917. The Battle of Vimy Ridge has assumed a special place in Canadian history. It was the first time that a large scale operation was carried out by all four divisions of the Canadian Corps. It was also the first truly successful offensive carried out by the Allies since the start of the war. (The French had twice tried to capture the ridge at a cost of 130,000 killed and wounded) But perhaps most significantly, it marked a turning point in Canadian history, for it brought a sense of national identity that never existed before. Some say that Canadian independence was bought at Vimy Ridge. It was costly, over 3600 killed and 7400 wounded.

| The Battle of Passchendaele stands as an unparalleled feat of arms in Canadian military history. The Canadians were successful where others had failed, in the face of overwhelming odds and a skillful, determined and confident enemy. It can be safely stated, that no battle in history was fought in worse conditions. Above average rain combined with poor drainage and unprecedented shelling resulted in a landscape in which landmarks were obliterated and the battlefield turned into a vast bog of soupy, sticky smelly mud. It clogged rifles. Food tasted of it. Guns sank in it, Soldiers slept, floundered and drowned in it. |

|

The Canadians went on to win 9 Victoria Crosses (the highest award for bravery given to soldiers of the British Empire) only one less than the entire number given out to Canadians in all of World War II.

By the time the Great War ended, the Canadian Army had built a reputation as one of the finest fighting units ever to be sent into battle, of always succeeding where others had failed. As General Sir Arthur Currie, the commander of the Canadian Corps from April 1917 until the end of the war said, "In no battle did the Corps ever fail to take its objective, nor did it lose an inch of ground, once that ground was consolidated; and in the 51 months that it had been in the field the Canadian Corps has never lost a single gun (i.e. no piece of artillery was captured) I think one cannot be accused of immodesty in claiming that the record is somewhat unique in the history of the world's campaigns". Truly remarkable, but with great cost - over 54,000 were killed, 126,000 were wounded and over 4,400 were never accounted for.

For a direct link to the author of this article, EMAIL TOM ARNOTT

![]()

Copyright © Tom Arnott, September,

1997.

Copyright © Tom Arnott, September,

1997.

Go to the next article in the series

Return to Tom Arnott's Start Page

Return to the Hellfire Corner Contents Section