PHILIP EAGLES

![]()

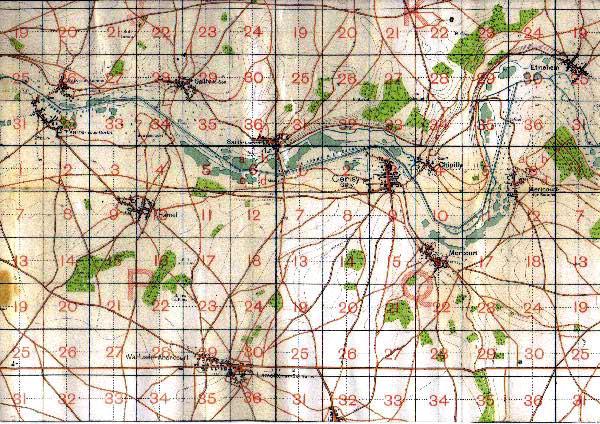

In the early hours of the morning of the 8th of August 1918 a blanket of fog around the river Somme concealed a massive military force which was about to be unleashed. As aircraft flew overhead tens of thousands of troops were on the march and four hundred tanks rumbled forward to the start line with engines throttled low to minimise noise. Two thousand British, Australian, Canadian and French cannon were deployed in a line stretching south-west from Hamel and north to and beyond the Somme.

To the north of the river were two divisions of the British Third Corps to the south four Australian Divisions, two Canadian and on the far right two French Corps. There task was to drive the German army back from Amiens and to inflict a defeat which would further undermine Germany's flagging will to continue the war.

In the line of artillery not far from Hamel were the twelve 18 pounders of the 38th and 39th batteries of the 10th Field Artillery Brigade of the Australian Imperial Force.

Amongst the crews of the 38th was my great-uncle George William Jessop who was then 21 years old. From Launceston Tasmania, George was a talented watercolour painter and sketcher who had been apprentice to a professional artist for four years.Away from home for nearly three years by August 1918, he had followed his older brother Alf into the Australian artillery having served as a cadet before the war. And it had been nearly a year since Alf had died of wounds received in fighting around Ypres. George had, no doubt often thought of him and of his family on the other side of the world. But as the seconds ticked down to Zero hour everyone's mind must have been on the job that had to be done.

To the east were the German lines, the X1 and 51 Corps their main artillery position in a valley which stretched south-west from the riverside village of Cerisy to Warfusee. From their dugouts and trenches the German troops looked out for sign of raiding parties. Did they suspect what was about to happen?

As watches ticked over to 4.20am the earth suddenly began to shake. Thousands of shells punched through the fog then exploded in a storm of shrapnel a few seconds later. The defenders could only keep their heads down and hope to survive.

As the Allied crews worked their guns a phalanx of troops and tanks began to move forward. One thousand 18-pounders lay a curtain of fire ahead of them delivering a devastating spray of 'daisy cutter' shrapnel which lifted 100 yards every two minutes. 4.5" howitzers bombarded 200 yards beyond that while heavy artillery concentrated on villages, woods and strong points further on. Close behind the barrage a line of Mark V tanks rumbled forward as nearby infantry scouts spotted German strong points for the crews inside who opened up with 6 pounder cannon and machine guns. 150 yards back came massed infantry deployed in files of sections.

North of the Somme where higher ground overlooked the plain to the south, the British Third Corps advanced with difficulty over terrain broken up by villages, woods and gullies. The commanders knew they would have to keep pace with the troops on the south side of the river or the flanks of the Australian divisions would be exposed to German fire.

At 6am the limbers and ammunition wagons of the 39th battery came forward as scheduled. The guns were hooked in and the battery moved forward 4000 yards into the valley which ran south-west from Cerisy. With dense fog around them they could see little of what was going on. But it was clear that the success of the initial phase of the advance had been dramatic. Most of the German artillery had been abandoned. Prisoners were streaming back towards the rear. On the eastern side of the valley the Australian infantry were digging in as the battery opened up again searching and sweeping the ground ahead. But German machine guns concealed by the fog continued to fire nearby.

At 7am the 38th, still in the main barrage line ceased fire and moved

forward along the road from Hamel to Cerisy amongst a mass of troops, tanks,

artillery and prisoners. And as the leading tanks approached Cerisy with

the 15th battalion, the 38th took up position nearby in support. Ahead of

them was a ridge running south from the village.

On the north side of the river the German officers trained their field glasses on shadowy figures moving to the south. The fog had begun to clear.While the Thirds Corps was struggling to get forward against fierce resistance the Germans observed that on the plains to the south of the river their lines appeared to have washed away. Massive columns of Allied troops were moving eastward against little opposition. The Germans turned their guns to the south.

Tanks crashed into Cerisy knocking down the buildings and opening fire on the German garrison before three companies of the 15th battalion stormed in taking several hundred prisoners from amongst the ruins. But on the far side of the village German machine guns and mortars opened up on the tanks battering their hulls with metal. Heavily armed German troops were lining a bank on the the eastern side of the ridge, machine guns were blocking the road. And from across the river hostile fire began to rain down on the troops who had begun to dig in around Cerisy. The tanks turned about unable to outflank the ridge. But on its western side others had already begun to climb. Three moved past the crest rumbling over a sunken road through a veil of fog and smoke. Suddenly machine guns bullets streamed out from the far side of the ridge. The tanks faultered then erupted in flames the crews fleeimg the wreckage some captured by the Germans whose fear had turned to anger. The prisoners were herded back to the cover of the bank where hundreds of Germans under Major Von Rathenow had sheltered from the barrage while training their machine guns on the crest of the ridge.

![[Image]](pict205.jpg)

Mark V tank. AWM Image

From their position in the valley near Cerisy the gunners of the 38th watched as more tanks climbed the slope followed by the fourth company of the 15th battalion. All seemed to be going to plan. Then one after the other explosions shook the ground. The tanks erupted in flames. But still the infantry pushed on up the slope past the blazing wreckage advancing over the crest until Von Rathenow's machine guns cut down many of them driving them back to the cover of the sunken road. Shells began to explode around them.

Back in the valley Major De Low and Lieutenant Jolly of the 38th battery mounted their horses and rode to the top of the ridge. Scanning the high ground north of the river with their field glasses they could see German crews working their guns near Chipilly. But they were too close to be targeted by the 38th on the other side of the ridge. Returning to the battery Major De Low ordered two guns to be retired 1000 yards down the Hamel road. But as they drove off Lieutenant Lintott with the remaining section spotted the flash of a German battery in Celestin Wood. Through their field glasses the German Officers could see the Australians as they turned their guns loaded and opened fire. But the Germans had their range and with one shell felled the Lieutenant and one of his crews. Gas shells lobbed into the valley and the remaining gunners took cover as ambulances raced forward to help the wounded. Drivers and teams dashed out to collect the guns but German fire drove them back. Meanwhile in Cerisy the 15th held out under fire as traffic on the Hamel road stopped or diverted to the south.

Major De Low's retired section unlimbered and moved their guns into position. Where was the Third Corps? The orders were that the Australian artillery should not fire north of the river but... Spotting the German guns in Celestin wood the section quickly opened fire. But once again the enemy countered landing a shell which put them out of action with casualties.The Germans continued to sweep the Hamel-Cerisy road with fire. There was no shortage of targets. Did they notice as the survivors of Major de Low's crews hooked up their guns again and moved off? Nearby, trees lined the banks of the Somme. And suddenly from the cover of those trees a shell roared out from one of the Major's 18-pounders exploding under the muzzle of one of the German guns. At last a blow had been struck. But much damage had already been done.

Back on the Cerisy ridge south of the 15th battalion the 14th battalion was getting forward. Overcoming a group of defenders on the crest they pushed forward beyond the sunken road until they too were halted by machine gun fire. Meanwhile the 39th battery under Captain Webber with a section of the 38th galloped forward over the southern end of the ridge and into a valley which ran south-west of Morcourt. Beyond the village on a hilltop 1300 yards away German machine guns were holding up the advance. Under fire two of Captain Webber's guns were run up to the crest of the next ridge. Bullets buzzed around them. But they silenced the machine guns with a barrage of 100 shells then fell back to join the rest of the battery virtually unscathed. As they did a tank and troops of the 14th battalion moved forward towards Morcourt while on the Cerisy ridge more tanks pressed forward down its eastern slope. The Germans still occupying the bank heard the tank's guns begin to blaze enfilading them from the flank. Major Von Rathenow gave the order to fall back. Thirty of his men dashed for the bridge to Chipilly but were sprayed with machine gun fire. They turned and ran for their lives while others abandoned the bank and fled towards Morcourt as Australian troops streamed over the ridge to where Von Rathenow's heavy machine guns sat abandoned amongst ammunition strewn over the ground. Dispirited Germans emerged from dugouts to surrender.

![[Image]](pict208.jpg)

Captured German artillery. AWM Image

Meanwhile troops of the 14th battalion pushed into Morcourt and found a mass of equipment, supplies and hundreds of Germans no longer willing to resist. The remaining guns of the 38th moved forward again over the Cerisy ridge into the valley close by the 39th. There they fired round after round at German troops assembling in the woods north of Mericourt.

South of Morcourt the 13th battalion had taken a wooded gully filled with abandoned German supplies and equipment. But as they moved up the ridge beyond it machine guns, snipers and artillery opened up cutting down sixty men in the space of a few minutes. Without tanks they could make no headway but as they dug in the sound of rumbling vehicles came from behind. Four tanks moved over the ridge and into the next valley struggling with a load of troops inside. Slowly yet terrifying enough to induce dozens of German troops to surrender without a fight. But again the German artillery north of the Somme intervened.Fearing the Australians were about to cross the river and outflank their positions at Chipilly they desperately bombarded the tanks as they pushed on towards Mericourt. Inside the vehicles was a hellish mixture of the noise of straining engines, explosions and the rattle of machine guns. For the passengers the uncertainty of what was happening around them must have been near unbearable. Veering right they climbed the slope south of Mericourt. But before long one turned back then another was hit and burst into flames. Two more pressed on along the ridge through the German lines before being battered to the point of destruction. From inside those who survived spilled out burnt and choking taking cover in shell holes while others opened fire with Lewis guns. Could they hold on? The 16th battalion were on their way up. Advancing in short rushes under covering fire they made it to the ridge in time to save some of the exhausted tank crews and to take the German trenches along with 200 prisoners and 12 machine guns. They had taken the final objective. But the Australians having suffered particularly in the northern sector could only hope there would be no counter attack in strength. Their opponents though had little left to throw at them. And the Germans in the north were now well aware of the massive columns of Allied troops advancing to the south against little resistance. Overhead aircraft swooped and straifed their positions while the Australian artillery turned all available guns on the German batteries in Malard and Celestin Woods. And as the Thirds Corps pushed forward level with Cerisy the Germans abandoned them and fell back.

Across the front of the Australian, Canadian and French Corps the German line had crumbled. Only those within reach of the northern German artillery had resisted significantly. Thousands of demoralised German troops had readily surrendered while vast amounts of supplies and equipment had been abandoned.

|

A few days later George Jessop wandered amongst the captured equipment snapping photographs of piles of machine guns, rows of mortars, cannon, anti-aircraft guns and searchlights. At the time did he appreciate the signifigance of what had occured? Were his recollections of the day affected by the casualties suffered by his battery perhaps some of them his own 'mates'? We will never know. But we do know the German General Ludendorff called the occasion a 'black day' for his army lamenting the readiness with which thousands of his troops had surrendered. |

The Allies had survived his great offensives of early 1918. they had learned from the costly battles of the Somme 1916 and Passchaendale. And while the events around Cerisy had shown that eelements of the German Army well handled could still inflict heavy casualties it was clear that the Allies' use of artillery, tanks, aircraft and infantry in close cooperation provided the formula for the eventual winning of the war.

In seven months time George Jessop would be sailing for home.

![[Image]](pict204.jpg)

George Jessop (centre) in 1951 with brother Angus and wife Elsie

(photo courtesy of Mrs. K. Burley)

AWM images reproduced by courtesy of the Australian War Memorial Canberra.

For a direct link to the author of this article, email Philip Eagles

![]()

Copyright © Philip Eagles,

September, 2002.

Copyright © Philip Eagles,

September, 2002.

Return to the Hellfire Corner News Section