ALASTAIR

H FRASER

|

![]()

Since 1997 a group of archaeologists, historians and enthusiasts have been carrying out a series of digs, mainly in the village of Auchonvillers, in conjunction with a project to collect information on the immediate front line area. One of the fascinating elements of First World War archaeology is how it can be used with the abundant historical record to enhance our understanding of the conflict. The historical aspect encompasses the use of British, French and German sources such as maps, regimental histories, personal and official diaries, printed histories, cine film, ground and aerial photography and geophysical survey. As project historian I have been working on this for about seven years and with help from contributors all over the world I have amassed an impressive amount of material on one small section of the Western Front. The group was initially known as Trench Team but was reconstituted in December 2003 as No Man's Land: the European Group for Great War Archaeology.

In October 2003 we were invited to participate in an archaeological investigation to be conducted in a field east of the Serre to Mailly-Maillet road on the old Somme battlefield. The area was the site of a position known as the Heidenkopf or Quadilateral and the object of the dig was to locate the dugout used by Wilfred Owen in early 1917, which featured in his poem "The Sentry". The work was filmed by the BBC and was shown in Britain on BBC2 in the Ancestors series. Unfortunately time constraints meant that the probable site of Owen's dugout was not reached but the remains of three soldiers were uncovered, one British and two German. This article sets out the process by which one of the German soldiers was identified.

Following the discovery of the three sets of remains the team began work on the process of attempting to identify the men. I was not present at the dig itself so I had to rely on the evidence provided in documents, photographs and interviews supplied by the digging team. The investigation was started by myself in Britain and Volker Hartmann in Germany. One German soldier, the subject of this study, has been identified and we are hopeful that documents found on the second German may result in his identification as well. The British soldier was a member of 1st King's Own (Royal Lancaster) Regiment and was killed on 1st July 1916 but efforts by CWGC and ourselves to identify him have been unsuccessful. He was buried this summer in Serre Road No.2 cemetery, very close to where he fell.

German no.1, as he was then known, was found lying on his back in a small depression east of a German trench near Serre Road No.2 cemetery. His head was missing, probably removed by subsequent ploughing, and he had no headgear or personal weapon although the remains of his uniform, ammunition pouches and bread bag were still in situ. These presented some interesting features from which it was possible to make a reasonable deduction on his unit and date of death.

There are considerable difficulties inherent in an investigation of this nature. Despite battlefield clearance and burial in July 1916, the spring of 1917 and after the war the Heidenkopf or Quadilateral position is likely to contain large quantities of human remains from the British, French and German armies. The history of the German 121 Reserve Infanterie Regiment for 1st July 1916 sets out the scale of the problem. "There were about 150 German dead in the Heidenkopf in a relatively small area and about three times that number of English." This area was fought over in October 1914, June 1915, July and November 1916 and March and April 1918. Added to that it saw routine trench warfare during much of the period, with mortaring, shelling and sniping likely to cause fatal casualties.

It is also worth bearing in mind that although the German Army had a precise, highly detailed and well documented system of regimental identification this did not long survive the outbreak of war. Identification of units from surviving uniform remains may not be reliable. Photographic evidence shows that German army units often did not adhere to strict uniform regulations from 1914 onwards. War raised units were formed from companies taken from a variety of regiments who may have retained their original uniform issue. Various patterns of obsolete, hybrid or stopgap equipment and clothing were issued to cover deficiencies, a process demonstrated with German no.1. As the war progressed regulation uniform items were often modified to retain older features, for example the M1915 Bluse, intended as a simplified, economy measure, frequently had cuffs and other details altered or added to. Conversely tunic decoration was often removed to hinder the identification of units by the enemy. Due to clothing shortages the Germans also repaired or modified clothing taken from casualties and reissued it to other soldiers.

Photo 1: left arm and pelvis of German no.1 showing the arrangement of the buttons on the cuff (right) and at lower left the lid of a polish tin, which was probably in the tunic pocket. The remains of the ammunition pouches can be seen in the chest area (upper left)

From the button arrangement it was clear that the soldier was wearing an M1910 Waffenrock tunic, which might suggest an earlier rather than later date. Most significantly the cuffs were of the Swedish pattern with two buttons parallel to and below the edge of the cuff turn-back. The more widely used type was the Brandenburg cuff with three vertical buttons. Swedish cuffs were fairly widely worn throughout the Imperial German Army but significantly were common in Wurttemburg infantry regiments. This was an important clue as it was known that this sector was occupied from March 1915 to November 1916 by 26 Reserve Division, a Wurttemburg formation. Equally important was the fact that after an exhaustive search of regimental histories and reference books it was found that the only regiment in 26 Reserve Division that wore Swedish cuffs was 121 Reserve Infantrie Regiment. This regiment was known to have been in the area both in June 1915 and July 1916 when there was heavy fighting and therefore a good possibility that casualties were not recovered. Bearing in mind the need to be cautious about identifications, it was possible that the man was from this unit.

The soldier's equipment comprised a set of M1895 ammunition pouches suspended from a leather belt. The pouches contained 190 rounds of 7.92mm ammunition with date stamps ranging from 1911 to 1913, which again indicated an early war date. The pouches were an obsolete pattern often issued to reserve units and there is photographic evidence from their history that 121 RIR was in part equipped with M1895 pouches. One somewhat misleading feature was the belt, which had a corroded but legible buckle with the motto "In treue Fest". This pattern of buckle was used by the Bavarian army, which was at variance with increasingly strong evidence that the man was from Wurttemburg. However it was a composite, two piece buckle, which suggested an early date. From what we now know it seems that the owner had acquired it during pre-war military service or from Bavarian troops who were briefly in the area in October 1914. It is certainly as well to remember that men might well be in possession of non-regulation kit.

The man's bread bag (Brotbeutel) was on the right side of his body. The contents did not assist with identification and were by and large in poor condition. They included a comb, a mirror, a nail cleaner and possibly a spoon and an indelible pencil. However there was further evidence amongst the soldier's personal possessions that suggested that he could have come from the Stuttgart area, which was within the district from which 121 RIR was recruited. A glass pot lid was found in the area of the pelvis where it had possibly been in a tunic pocket. The legend reads "E. Breuninger zum Grossfursten. Munzstrasse Stuttgart Sporestr. Aussteuer-Waren, Putz-Artikel, Peltze, Gardinen, Teppische. Damen-, Herren- u, Kinder- Konfektion. Manufacturwaren, Besätze." This translates as "Trousseau, cleaning goods, furs, net curtains, Ladies, gentlemen's and children's ready to wear clothes. Textiles, trimmings." The lid also showed a view of Breuninger's premises. The firm of E. Breuninger still exists in Stuttgart although not on the same site as in 1914. They were contacted by email and although not able to say precisely what was in the pot they think that it was probably either shoe cream (Schuhcreme) or dubbin (Lederfett). The firm was founded in 1881 with three employees by Eduard Breuninger in a building beside his house Marktplatz 1 in Stuttgart. The building had originally been a restaurant called "Zum Grossfurst" and this name was incorporated into the name of the company and retained when it moved to larger premises on the corner of Munzstrasse and Sporestrasse. The firm of Brueninger were a large regional department store in 1914 with several outlets in central Germany. In the 1930s they claimed to be the largest retail firm on the European continent but seem to have lost this position after World War II.

|

During the excavation a badly corroded identity disc was recovered from the chest area and this seemed the best chance of identifying the casualty. However on cleaning it was apparent that not all the legend on the disc has survived and frustratingly it was an early pattern, which did not include the name of the individual. The only information on these discs was the regimental designation and number, the number of the company and the number of the individual on the company roll. |

From the remains of the disc we now knew that the man served with a reserve infantry regiment but unfortunately the number was missing; he was in 7 Kompanie and was number 2 on their roll, so presumably enlisted or re-enlisted in August 1914. Interestingly it was known that 7 Kompanie of 121 RIR were in the trenches that later became the Heidenkopf from 10th to 13th June 1915. During these few days there was heavy fighting and it was possible that the soldier had been killed at that time. They were not in that area on 1st July 1916, which was the other period at which one would expect unrecovered casualties. It was clear that the owner was uneasy about the lack of a name on his identity disc, as he had rather clumsily scratched some details on the reverse with a knifepoint or something similar. Again the corrosion had removed some of the legend but it was possible to read the top line as "Mun … ", the second line as "Hines", and the bottom line "Jak …". The difficulty was in deciding what this meant. The first line could either be part of a street name, a place name or a personal name; the second line made no sense at all as it is not a German surname or an identifiable place and the bottom line could again be part of a street or place name, a Christian name or a surname. Without access to full casualty lists for 26 Reserve Division we were unlikely to progress any further. The printed history of 121 RIR, the prime candidate for our man's unit, did not contain casualty rolls for ranks below Feldwebel Leutnant. There our investigation stuck for a couple of weeks.

I was fortunate enough to make contact with Ralph Whitehead on the World War One Forum. For some years Ralph has been researching the German XIV Reserve Korps on the Somme. He was able to supply a list of casualties for 121 RIR assembled from privately published lists and the officially produced Verlustlisten. Scrolling down to 7 Kompanie I found a Jakob Hones who was killed on 13th June 1915. Re-examination of the identity disc showed that the "I" of "Hines" was in fact an "o" with an umlaut. Ralph was also able to state that Hones came from a village near Stuttgart called Munchingen, which explained the first line of the scratched legend on the reverse of the disc. It was extremely satisfying that we had identified the man and also that our methodology had allowed us to make a spot-on deduction of when he was killed and what unit he was with.

Armed with this information Volker Hartmann contacted the archives in Munchingen and received some further information on Jakob Hones, including the astonishing news that one of his sons was still alive. Ernst Christian Hones was very frail and elderly and was not able to supply any useful detail on his father, whom he probably never knew, but he was pleased that he had been found and would have a grave in a German military cemetery. We were able to get some facts from the Hones family, many of whom still live in Munchingen and we are most grateful for their help and the photographs that they supplied. From this it is possible to produce a short biography of one German infantryman.

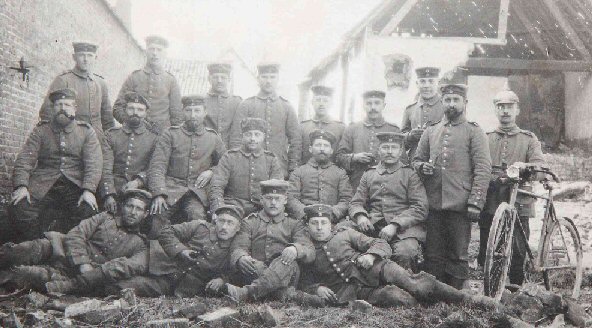

Photo.3: a group of German soldiers including Jakob Hones (front row extreme left, lying down). The Swedish pattern cuffs are visible on a number of men including Jakob but there are also examples of the Brandenburg pattern as well. There is no indication of where or when the photograph was taken or indeed who the other men are, although it is obviously fairly near the front line from the state of the buildings in the background. The man third from left in the middle row, with the Iron Cross 2nd Class ribbon, bears a resemblance to Jakob and it has been suggested that it might be his brother Christian who also served in 7/121 RIR.

Jakob Hones was born in Munchingen in Wurttemberg on 9th December 1880. He was one of at least three children and his profession is described in the Verlusteliste as Landwirt which translates as "farmer". The Munchingen archives however give his profession as Tagelohner which means "day labourer" or "farmhand". He probably did his military service from 1900 to 1902 and certainly served in 121 Infanterie Regiment whose depot was in Ludwigsburg. His wife was called Marie and they had six children, the last of whom was born in December 1914. Soldiers in the Reserve were liable for annual training so Jakob's military skills were probably kept up to scratch. He was called back to the colours on 2nd August 1914 on mobilisation and served with 7 Kompanie, II Battalion, 121 RIR, which was raised in Heilbronn. The second battalion was commanded by Major Otto Burger and the commander of 7 Kompanie was Oberleutnant von Raben. The German mobilisation of 1914 was an enormous undertaking, which increased the strength of the army almost overnight from about 800,000 men to over 4,000,000. It is hardly surprising that there were shortages of equipment and some men in 121 RIR had to make do with obsolete ammunition pouches. By 18th August the regiment was in contact with the French in the Vosges mountains and had suffered its first casualties. Jakob Hones probably had his baptism of fire the next day when II/121 RIR was committed to an attack near Breuschatel. Fighting continued around Nancy and Epinal until late September when the 26 Reserve Division was entrained for a move northwards as part of the series of outflanking moves that has wrongly gone down in history as "The race for the sea". The division was unloaded from its trains at Cambrai and marched down to Bapaume. They were soon fighting the French again in the Thiepval and Ovillers area. The night of 28th/29th September was a particularly unpleasant one and although 7 Kompanie escaped unscathed 5 and 6 Kompanie both suffered. The regiment suffered 20 dead, 212 wounded and 80 missing. The casualties included Major Burger, wounded by a stray bullet. Interestingly 4 Bayerische Infantrie Division was in the line next to 26 Reserve Division. It may be at this time that Jakob did a swap and obtained a Bavarian belt. As the line became more permanent 121 RIR occupied the southern part of the ruined village of Thiepval. Their sector stretched south to the Wundt-Werk with regimental headquarters at Mouquet Farm.

Life settled into a routine of trench digging and garrison duty. The weather turned colder in November and as Christmas came efforts were made to make the troops as happy as possible. In the Granatloch position (what later was known to the British as the Leipzig Salient) the men amused themselves by playing songs to the French on a gramophone. It must have been particularly depressing for Jakob whose sixth child was born that month. His younger brother Christian also served in 7 Kompanie, which may have been some consolation to him. Conditions out of the line were fairly comfortable and the division set up reading rooms, pubs and various recreational facilities. There was a visit from King Wilhelm II of Wurttemburg in April 1915 and on 20th May II/121 RIR was temporarily attached to 28 Reserve Division at Orvillers. It was from here the next day that Jakob sent a field postcard to his wife and children, which told them little more than that he was well.

By the end of May it was apparent that the French were preparing a major offensive. Their objective was the village of Serre the loss of which would be a serious blow to the Germans in this sector. The German trenches in front of Serre formed a salient into the French lines and the plan was to eliminate this. Artillery fire increased on the division's right flank and on the neighbouring 52 Division, as well as on the regimental positions round Thiepval; there was much greater aerial activity from the French as well. By 6th June 52 Division reported that the enemy had cut gaps in his wire obstacles and that the assault could not be long delayed. II/121 RIR were at the time out of the line with two companies (7 and 8) in Miraumont and two (5 and 6) in Courcelette, although the men were alerted and ready to move. The regimental staff occupied their battle headquarters and during the evening of the 6th the concentration of fire reached previously unseen levels on the division's right flank. On the morning of 7th June the French 2nd Army launched their assault and penetrated the German front line. II/121 RIR was warned to be ready to move and 7 and 8 Kompanie were moved up to the valley east of Beaucourt, called by the Germans Artillerie Mulde; it was later known to the British as Artillery Valley. A counter-attack was planned for that evening in conjunction with two companies of 99 RIR but this was called off, not before some casualties had been suffered from artillery fire. It may well have been at this point that Jakob Hones refilled his ammunition pouches for the last time. The two other companies were brought across the Ancre during the evening and that night the entire battalion was concentrated in the valley. The next morning 8 Kompanie was sent forward to fill a gap on the right wing of their sister regiment 119 RIR north of Beaumont Hamel. On the 9th June 6 Kompanie was also called to reinforce 119 RIR . The next day orders were received to move 5 and 6 Kompanie to Hill 143 north of Beaumont Hamel. Hill 143 was near the limit of the French penetration and the battalion was required to close the gap between 119 RIR and 170 IR further north. 7 Kompanie was as yet the only uncommitted company and moved out of Beaucourt towards the front line to join the rest of the battalion.

The approach march to the trenches that were later to form the Heidenkopf position was very unpleasant. Under heavy fire the men crossed old trenches and open fields until they arrived at the German second trench, the first line being in French hands. 7 Kompanie and the battalion staff occupied the trenches to the east of the Serre to Mailly-Maillet road. During the 11th the battalion endured more artillery fire and 7 Kompanie lost two men, one of whom may have been the other German recovered during the dig. Reinforcements arrived during the day in the shape of Leutnant Auerbach's platoon of the machine gun company and some men of 9 Kompanie but there was very little shelter in the position and casualties continued to mount, some men being buried alive. The next day was much the same but the artillery slackened off during the evening of the 12th only to resume again next morning. Two waves of French infantry appeared with columns of men behind them. The French overran the positions to the west of the main road and captured the survivors but were unable to get any further. The attack broke down under heavy rifle and machine gun fire 150 meters from the German trenches on the other side of the main road. It seems likely that Jakob Hones was hit and seriously wounded during the preparatory bombardment, as his full ammunition pouches indicate that he did not take part in the defence of the position. A shrapnel ball had penetrated his bread bag and a number of small shell splinters were found in the pelvis. It appears that he did not die immediately as a family story has it that his brother Christian was with him at his death. At some stage either before or after death Jakob was wrapped in a ground sheet. He may have been slung out on to parados of the trench and dragged for some distance by his feet, before being placed in the hole where he was found nearly 90 years later. The fact that the eyelet holes of the groundsheet were found round his body and that his pouches had ridden up to his chest support this interpretation. Jakob was reported as killed rather than missing, which would indicate that his death was witnessed. 7 Kompanie suffered badly that day; 18 men were killed, a further 6 were missing and declared dead and 3 died in enemy prisoner of war camps, presumably having been captured when the French took the position on the west side of the main road. A further 3 men died of wounds in field hospitals in Bapaume and one man, Vizefeldwebel Albert Schleh lingered on until July and died in a hospital in St. Quentin. In total II/121 RIR lost 311 casualties, 81 of them fatal, including Hauptmann Guido Nagel the battalion commander and Hauptmann des Reserve Gustav Hornberger, a company commander and a well-respected peacetime officer. However the French did not continue their assault, thwarted by what the regimental history called "the heroic resistance of the battalion."

Sadly the death of Jakob was only the first blow that the Hones family were to suffer in the Great War. A year later his brother Wilhelm was killed at Hill 60 in the Ypres salient whilst serving with 125 Infantrie Regiment and on 24th July 1916 Christian Hones was seriously wounded and died at the dressing station in Miraumont. Jakob and Wilhelm are commemorated, together with another Hones who may be a relation, on the war memorial in Munchingen. We had hoped that Jakob might be buried at Fricourt with some of his comrades but this cemetery is no longer open for burials. However on 26th August 2004 Jakob Hones was buried at Labry German Military Cemetery near Verdun. 14 members of his family were in attendance as well as Volker Hartmann, representing No Man's Land. By an extraordinary co-incidence a party of uniformed Bundeswehr signals personnel were present tending the graves. They were pleased to be able to provide Jakob and his currently unidentified comrade with a guard of honour. The past has an odd way of sometimes tugging at your sleeve. At some time Jakob Hones was concerned that his identity disc did not have his name on and that he would never be identified. The investigation has been a fascinating and successful exercise but most importantly we have been able to do a small service for a man long dead. He now has a grave with a cross that has his name on it.

Photo no.4: the funeral of Jakob Hones and his comrade at Labry German Military Cemetery with Bundeswehr personnel in attendance.

This project has been an extraordinary international collaboration and I would like to thank a number of people: Volker Hartmann of Wolfenbuttel for his work in Germany; Ralph Whitehead of Fayetteville, New York for all his information on German casualties, his translation work and allowing us the benefit of his immense knowledge of the Imperial German Army; Paul Blackett of North Shields who lent several rare works on the same subject and provided advice on German uniforms; the staff of the conservation laboratories at University College, London who have done excellent work on the identity disc and other artefacts. I also need to acknowledge the sterling efforts of my colleagues in the field who recovered and recorded the three bodies in a thoroughly professional manner, despite adverse weather conditions. Finally a word of thanks to the Hones and Rapp families who, quite out of the blue, were presented with a pretty much forgotten ancestor; they supplied us with photographs and biographical details and they turned out in force to honour him.

Alastair H. Fraser

Project Historian

No Man's Land: the European Group for Great War Archaeology

Bibliography

Battleground Europe: Serre, Somme, Horsfall, Jack and Cave, Nigel, London, 1996.

German Army handbook, April 1918, General Staff, British Army, London, reprinted 1977.

Handbook of the German Army in war, January 1917, General Staff, British Army, London, reprinted 1973.

Histories of the two hundred and fifty one divisions of the German Army which participated in the war (1914-1918), Intelligence section, General Staff, American Expeditionary Force, London, reprinted 1989.

Imperial German Army 1914-18. Organisation, structure, orders of battle, Cron, Hermann, London, 2002.

Ruhmeshalle unserer alten Armee, Cron, Hermann et al., Berlin, [1935].

Uniforms and equipment of the Imperial German Army 1900-1918. A study in period photographs, Wooley, Charles, Atglen PA., 1999.

Das Württemburgische Reserve-Inf.-Regiment Nr. 121 im Weltkrieg 1914-1918, Von Holtz, Georg, Stuttgart, 1922.

Die 26 (Wurttembergische) Reserve-Division im Weltkrieg 1914-1918, I Teil, von Soden, Stuttgart, no date.

For a direct link to the author of this article, email Alastair Fraser

![]()

Copyright © Alastair H. Fraser,

October, 2004

Copyright © Alastair H. Fraser,

October, 2004

Return to the Hellfire Corner Contents Section