![]() JOHN GUY GILLBERT

(Writing in 1963 - edited 2004 by Stephanie Horton)

JOHN GUY GILLBERT

(Writing in 1963 - edited 2004 by Stephanie Horton)

![]()

John Guy Gillbert

5th November 1891 - 7th November 1974

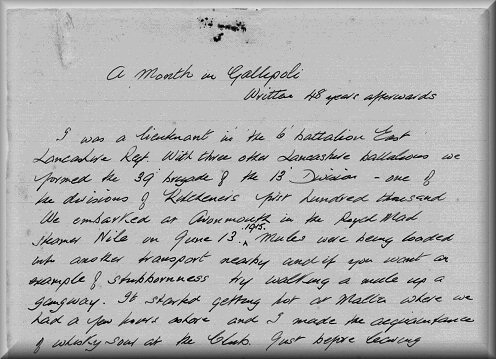

| I was a Lieutenant in the 6th Battalion East Lancashire Regt. With

three other Lancashire Battalions we formed the 38 Brigade of the 13th Division

- one of the divisions of Kitchener's first hundred thousand.

We embarked at Avonmouth in the Royal Mail Steamer Nile on June 13th 1915. Mules were being loaded into another transport nearby and if you want an example of stubbornness try walking a mule up a gangway. |

|

It started getting hot at Malta where we had a few hours ashore and I made the acquaintance of whisky sour at the Club.

Just before leaving England we had been issued with tropical kit and many of the men were laid out temporarily through exposing themselves to the sun too quickly. By the end of the voyage I had lost six layers of skin from each kneecap. Apart from occasional anti submarine duty - we had two machine guns on the upper deck - there was not much to do and four of us played bridge most of the time.

I had tremendous luck and won from everybody - some £15 in I all. I should have banked it in Egypt but I didn't and it eventually disappeared with the rest of my kit. The others remarked that they would be the lucky ones in the Dardanelles but I was the only one of four that returned. We spent only one night at Alexandria - subsequently I had many there - and did not go ashore. The two days steaming through the Aegean were beautiful - hot windless days with a blue violet sea. The island of Carpathos was crowned with a volcano which blew a perfect smoke ring every 20 minutes or so and a succession of 6 or 7 of these rings could be seen floating across the sky.

The night before reaching Lemnos we were entertained to dinner by the ship's officers who were all Americans and the champagne then contrasted sharply with the meagre water rations that we were to get later. Indeed in this campaign there could be no greater contrast than life in a nearby ship and that ashore. Next day we steamed past the long line of ships in Mudros Harbour and most of their crews came on deck to cheer us. We had done nothing to deserve this but we were the first reinforcements to arrive for some time. Lemnos was unfortunately brown, dry and hot; from the moment the sun struck over makeshift bivouacs about 5am until it disappeared at 7pm its heat was, to us, unbearable. There was little to do but to lie and look longingly at the GHQ ship "Arcadian" which - rumour had it - was aground on empty bottles! After three days there we went aboard the collier Hythe - famous in Gallipoli history - and arrived off the Dardanelles at daybreak. We went ashore at V beach via the River Clyde but there was little evidence of the terrible struggle there had been around her on April 25. That was on June 28 and as I didn't keep a diary the sequence of events for the next month until August 2nd when I was taken off in another collier to a hospital ship is not very clear. The general picture however remains vividly.

Overall was a great feeling of unreality as if we were all on a stage. For example, although for the 35 days we were never out of shellfire from the start no one paid any attention to it and just carried on with whatever duty or fatigue was on hand. A very early impression I well remember was a strong conviction that the campaign could not succeed. Although we were really civilians and not soldiers and had had no previous experience, a lot of us felt this. It didn't affect our keenness in any way but it was just our summing up of the situation as we saw it.

At this time and for all practical purposes the ground we occupied stretched for two miles across the peninsula and was about two and a half miles in depth from V beach up to the front line. I remember that we spent the first night in the Eski Lines - a deep wide support trench. Bullets and ricochets whistled over most of the time but already we had learnt to sleep unless we were officially awake. The next few days were spent under the cliffs on the western side which were some hundred feet high. Near the top and just over our battalion HQ was a 60 pounder gun - a relic of some bygone campaign. It fired about three times a day and that was a measure of the shell supply. Here the men were acclimatizing and I admired how good they were at it. Most of them were miners from Burnley and had probably never been further than Blackpool in their lives before. They were all volunteers and there could be no glory in it for them but every drawback - and there were plenty of them - only called forth their Lancashire humour second only to the cockney or even equal to it. During our 9 months of training in England most of them had their domestic troubles with wives or sweethearts but these had all gone - no-one could now write and worry them. Bathing was possible here and now, we had our first casualty. It seemed strange that a man should have undergone so much preparation just to get drowned on a strange shore. The best Gallipoli story I remember was about bathing. The ANZAC troops used to bathe - with a sentry to watch them when a shell from the Asiatic Coast was on the way. An Australian tommy saw a posterior emerge from the water and took a resounding slap at it. The owner emerged very angry and demanded "What the hell do you think you're doing my man - don't you know who I am. I'm General Birdwood!" Came the reply - "Then why don't you cover your backside with feathers like any other bird would!" - probably apocryphal but worth recounting. Incidentally General Birdwood who commanded at Anzac was one of the three men who was on Gallipoli from the landing until the evacuation.

A most unpleasant task was done here. A week or two earlier a cattle boat had been sunk off the coast and the horribly distended carcasses were now being washed ashore. The stench was unbearable and fatigue parties were told to tow them out to sea and sink them by firing into them.

One afternoon here our C.O. Colonel Cole Hamilton had a visit from his kinsman General Sir Ian Hamilton who was rowed ashore from a destroyer and stayed to tea. Being battalion signalling officer I was at battalion HQ and at the tea. I can only remember that it was not a very cheerful occasion. Our brigade - the 38th - signalling officer was H.G.J. Moseley a brilliant young physicist who only a year or so previously had discovered the theory of atomic numbers. Here he went out between the trenches one night to salvage some disused telephone wire and was killed by a stray bullet. This was only one example of the way in which many of our very best young men were lost - he should never have been allowed to enlist.

A vivid memory of our stay under the cliffs is the smell of small campfires and the cooking thereon. Our main rations were bully beef and ships biscuits. The bully was cooked in a variety of ways; the biscuits were ground up for pastry making. The daily water ration was two pints which later in the front line was to be reduced to one. With an average day temperature over 90 the same water had to be used in more than one way before being ultimately consumed!

From here we moved up along the coast to The Gully. This was the biggest ravine in the Helles Sector; it ran inland from the sea - just short of the ill fated Y beach - for a quarter of a mile and then turned north and parallel with the coast for two miles or so. As a result the upper half was in Turkish hands and this they had barred off with an immensely strong barricade of upright tree trunks laced with especially thick barbed wire; it would need an explosion to break it down. The gully was narrow with steep sides so that the bottom of it was free from shellfire. In the mouth and a short way in from the sea was a grave and inscription to Major Geoghan - of the Munster Fusiliers I think - who had taken his men ashore in the original landing.

It was now thought that we were sufficiently acclimatised to take our place in the front line. We were not to be trusted on our own however and for some days our units were intermingled with those of the 1st Essex Regiment - a unit of the immortal 29th division which had made the original landing at Cape Helles. From them we were to learn all the tricks but really they boiled down to one - never show your head above the parapet - day or night. The Turks had machine guns sited on to our parapet - they changed the position each day - and during the night they would loose off a few rounds at irregular intervals. In reality there was very little more danger in the front line than elsewhere unless either side was proposing to attack. This part of the front had been captured in an advance we had made on the 28th of June and as a result there were number of dead Turks out in front. I shall never forget the strong sickly smell of bodies which had been in the hot sun for a fortnight. Our men had failed to capture the next trench and on the barbed wire in front of it were the bodies of many Scotsmen from the 54th Division - a terrible sight.

About this time the flies began to get really bad; there were swarms of them everywhere. They were chiefly bluebottles or rather blue and green bottles. I saw a tommy open a tin of jam - plum and apple of course - spread some on a biscuit and try to get it to his mouth without half a dozen flies settling on it but it was almost impossible.

There was very little signalling to be done here as battalion HQ was practically on top of the companies. A maze of telephone wire ran along the sides of the trenches - sometimes looped up on projecting bones - but most of them were not in use. The men of the Essex Regiment - it was down to a quarter of its original strength - were most helpful and cheerful and the battle of wits between Essex and Lancashire was always most entertaining. After a week or so in the front line battalions were relieved and sent back a mile or so the reserve trenches. Life here was not very different from that in the front line except that it was not necessary to stand to at dawn in case of a Turkish attack. An extra hazard however was the presence of Turkish snipers behind our lines. These men could cover a few yards of some of our rear trenches and there were generally notices posted up warning of the danger. It was said that some of the snipers were posted in trees - although there were mighty few trees about; in any case it is difficult to see how they could have survived for nearly three months behind our lines.

Our next turn in the front line was the furthest point reached on the western coast. This was named Gurkha Bluff because it had been captured by these troops in the limited advance a few days earlier. The Gurkhas were grand troops - small fellows but tough as nails and natural fighters. They were used to the heat and other drawbacks and the Turks were more afraid of them than of any other troops. There was an obvious advantage us having both our flanks resting on the sea. At the same time we could not outflank the enemy either but I doubt if this would have helped much. For one thing such maps as we had were practically useless - I still have my three. Only maps of the trench systems would have been of any use at that time and these systems were very intricate and of course haphazard. As an example when a battalion in the front line was to be relieved it had to send guides back to the incoming troops, as no written description of the way could have been trusted.

It was now the end of July and there were rumours of a new plan and offensive but as there were always plenty of rumours no one paid much attention to this one. I had not been feeling very well for some days but health out there was relative and I thought it might be an attack of dysentery which by then was very prevalent. Then one evening I could hardly stand up and the battalion M.O. ordered me back to the base hospital on V beach for examination. I don't remember going there but next morning the M.O. there told me I had typhoid. That same evening I was carried aboard a collier where I lay on deck amidst many other sick and wounded. A short way off shore we were transferred to a hospital ship - the Neuralia. The dining saloon had been made into one large ward and I have a recollection of the matron - the first woman I had seen for six weeks - exhorting me to cheer up and smile; this was just about the last thing I was capable of. When I woke the sea was very quiet outside the portholes and I asked the nurse when we were going to sail. She said that we were in Alexandria harbour and that I had been unconscious for two days and that they had kept me going on champagne - what a waste of champagne. I spent five weeks in an ANZAC military hospital at Ras el Tin with a wonderful staff of doctors and nurses. I had been inoculated against typhoid in England and but for that I might have been worse although it was bad enough. The only deaths from typhoid in the hospital while I was there were among naval officers who had not been inoculated; in the army inoculation had been compulsory to all intents and purposes. After I had been there a week or so an Australian Captain was brought to the bed next to mine. He had been wounded in the attack on the Turkish stronghold of Lone Pine an attack made to pin down the enemy during our offences at Anzac and Suvla. It was one of the bloodiest struggles of the campaign and he told me how some of the Australian who were to be kept on reserve had offered up to five pounds to be allowed to take part in the attack. I had seen some of the Anzac troops in the peninsula; they were of magnificent physique, and often wore only shorts and entrenching tool carriers on their feet. They had no military discipline in the British sense but were as fine soldiers as had ever taken the field.

After some five weeks on a liquid diet I was told that my temperature had been down for 48 hours and that I could have solid food the next day. All that night I lay awake waiting for it and at last when it came it proved to be 2 dessertspoonfuls of Bengers food - a smear on the bottom of the plate; nevertheless I took about an hour to eat it.

A fortnight later they told me that the last ship to take typhoid cases to England would leave the next day and that I should be aboard. It was the hospital ship Tagus of the Royal Mail Line and there were some five hundred invalids on board, many of them stretcher cases. The voyage was delightful for me although in the Bay of Biscay we ran into an equinoctial gale which carried away all our red and green hospital ship lights on the port side. That night at dinner there were some dozen patients, three nurses and not a single doctor. I was put ashore at Southampton in pyjamas, slippers, a dressing gown and a solar topee which had all been supplied by the Red Cross. My kit - uniform, revolver, binoculars etc - had been packed in my valise and taken with one to the base hospital at V beach. The valise was returned to me in England three months later and contained only the three maps already mentioned.

Meanwhile the 38th Brigade had been moved to Anzac where it was kept concealed. On the night of August 9th it set out under its Commander General Baldwin to reinforce the thin line of troops holding the ridge of Chunuk Bair. This ridge dominated the Narrows and was the key point in the campaign. The guides leading the column lost their way in the very difficult country and at daybreak the brigade was at the foot of the hill instead of on the top of it. The Turks had been strongly reinforced and shortly afterwards they came over the hill in great strength and overwhelmed our men. After a hand to hand struggle around a small farm at the foot of the hill our men were forced back down the narrow gully by which they had come up. General Baldwin and Colonel Cole Hamilton were killed and the 6th East Lancs lost 18 officers killed and wounded out of the 24 who had started out the previous night. This was the last serious offensive undertaken by either side during the campaign which was to linger on for another four months before the very successful evacuation.

JOHN GUY GILLBERT 05:11:1891 - 07:11:1974

John Guy Gillbert born 5th November, 1891 in Tottenham, London. He was the eldest of 3 boys. His father was a schoolteacher in Tottenham.

John won a Scholarship in 1909 when he was 17 years old to Lincoln College, Oxford to read Chemistry and Mathematics he was awarded a First.

After Oxford, we believe he then worked for Brunner, Mond & Co. in Cheshire.

1914-1918 Lieutenant in 6th Battalion East Lancashire Regt. - Signalling Officer, Gallipoli. When he came back from Gallipoli he went to work in laboratories in Swindon.

Married Miss Kathleen Perry on 4th June 1919, only daughter Mary Eleanor born 10th September, 1922.

Career in Imperial Chemicals (Brunner, Mond & Co. amalgamated with other chemical companies in 1926 to form Imperial Chemicals) included travelling to China, Japan in 1920s. Imperial Chemicals Managing Director, Technical Division.

1939-1945 - Worked developing ammunitions for the war. We have also been told he was instrumental in the development of Paludrine for the fight against so many in the Far East /Africa dying from malaria. Acting Chairman of Technical Division for the war years and until his retirement

He retired early at the age of 55 years old, exhausted from his efforts during the war and after. He and his wife retired to Flushing, Cornwall and spent their leisure time sailing and looking after their 2 grandchildren. They moved to Amport, Hampshire in their later years to be near their family.

John died 7th November, 1974

For a direct link to the editor of this article, email Stephanie Horton

![]()

Copyright © Stephanie Horton,

March, 2004.

Copyright © Stephanie Horton,

March, 2004.

Return to the Hellfire Corner Contents Section