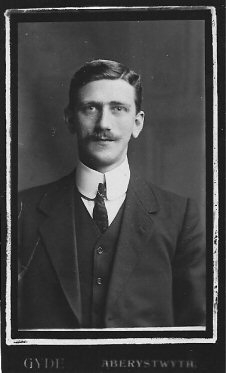

![]() JOHN HARTLEY

JOHN HARTLEY

![]()

The Early Years

Today, Cheadle is a pleasant suburb of Stockport. Most of the area is 1930s housing surrounding an older centre. It was in the news in 2005, when a parliamentary by-election was fought there.

Back in 1914, it was a large village - one of several which made up the area of the Cheadle & Gatley Urban District Council. It was a thriving community with two railway stations and a tram line running to Stockport. The Council had its offices on the High Street and one of its senior employees was Isaac Worthington, the Collector of Rates.

Isaac had married Jane Roughton at the local parish church in 1871. They would have seven children together and, as was common in those days, all the children would have Roughton as a middle name. When the future soldier, Thomas Roughton Worthington, was born in 1882, he was their fourth child (and second son).

Tom grew up to be a keen sportsman and played hockey for the local Cheadle Club and, also, at the nearby Bramhall Club. He worked as an accountant for a company in Manchester. Locally, his best friend and neighbour was another of the village's middle class young men - Alexander Milne, a solicitor's managing clerk, who also worked in Manchester. It is, perhaps, not fanciful to think of them travelling together to and from work by train.

Also in his spare time, Tom was a long-standing member of the 6th (Territorial) Battalion of the Manchester Regiment. His service number (637) indicates he was, almost certainly, a member of one of the Volunteer Battalions which became the Territorials in 1908. He would have given up a night or two each week, or a Saturday afternoon, to train at one of the Regiment's drill halls - probably the Battalion Headquarters on Stretford Road (on the outskirts of the city centre). Locally, their uncomplimentary nickname was, indeed, the "Saturday Afternoon Soldiers". Tom was reported to have been a "crack shot" with the rifle and had won many prizes. They also trained at an annual camp in the summer, which was often a highlight for men unused to travelling far from home.

In 1908, there would also have been much to celebrate in the Worthington household, when Tom's sister Agnes got married to a local man, Walter Bennison. Their daughter Kathleen was born sometime between 1912 and 1914. The Bennison's are a later part of this story.

The First Weeks of War

The role of the Territorials in times of national emergency was one of home defence. The men were not obliged to serve overseas. However, as recorded in the History of the 42nd Division, "Few members of the Territorial Force had realized that their calling -up papers had been ready from the day they joined; that month by month the addresses on envelopes were checked and altered when necessary; that enough ammunition was stored at the various headquarters to enable every man to march out with the full complement of a fighting soldier; and that field dressings were available for issue."

In early August 1914, many of the Division's units were in their annual camp and they were recalled to their home bases on 3 August. The next day, war was declared. The Division was mobilised and the envelopes were sent out. Within hours, Colour Sergeant Tom Worthington and his comrades would have started to assemble at Stretford Road. Men were quartered in nearby drill halls and schools. Private Alexander Milne is thought to have been amongst them, although his service number (2475) indicates he had not been a Territorial for very long. On 10 August, Lord Kitchener invited members of the Territorial Force to volunteer for overseas service and over 90% did so. For another few days, the men remained around their Battalion headquarters but, on 20 August, the Manchesters moved to Hollingworth Lake, near Rochdale. The move to camp was described in the Rochdale Observer:-

"The Manchester Territorials made an early start. They were out and about, soon after three o'clock and were in route formation by five. At that hour, the 6th Battalion moved away from their Headquarters in Stretford Road, half an hour later the 7th left Burlington Street and the men of the 8th from Ardwick bringing up the rear. The departures were watched by crowds.

The 6th Battalion came through in a very soldierly fashion. Officers riding and one or two mounted men were in a van, a cycling contingent followed and afterwards, four abreast marched the "Terriers". A machine gun or two and quite a number of horse drawn vehicles laden with stores brought up the rear…..There was no ban on pipe or cigarette. Here and there water bottles were raised to dusty ready lips. It must have been no joke this full kit march, with rifle, ammunition, other service requisites and the greatcoat strapped behind the shoulders - a total weight exceeding 60lbs."

Over the following days, the men spent most of their time undertaking route marches and other drills. Rumours quickly circulated that they would not be at Rochdale for long. In the way of all rumours, it continued to develop and, by early September, the men were convinced that they would be going to Egypt. And so it was. On 9th September, the whole Division entrained for Southampton. Over 40 trains were needed to move the men, horses, guns and supplies. The next day, a convoy of vessels left harbour. They were the first Territorial Division to go overseas.

The official history of the Division notes that there was rough weather for the first three days of the voyage. "It was noticed that even the worst sufferers from seasickness never lost hope as, although whole messes did not eat a meal in those three days, the daily indent for one bottle of beer per man was always drawn." The rigours of the Bay of Biscay were soon passed and, during the convoy's progress across the Mediterranean, they passed a great fleet sailing the opposite way. It was the Lahore Division bound for Marseilles. The men disembarked at Alexandria on 25 September and Tom and his comrades remained in the city as part of its garrison.

Over the following weeks the men were put through a strenuous programme of training, including long route marches through the desert. But there were opportunities for sport and competitions were soon being held in cricket, football, rugby, lacrosse and, to Tom's great pleasure, hockey.

Writing home, Tom recounted that the Battalion had marched to Aboukir and back, a distance of 20 miles. "The country is very flat and seems well cultivated, but the people are dirty and the houses miserable. We saw one or two real mud huts".

In another letter, Tom said that the sergeants had served a Christmas dinner to the men. "On the Saturday, we had hockey, morning and afternoon and went to the pictures in the evening. There are several rooms where we can read and write and enjoy ourselves and even make friends with the people here, so we are not cut off from the world as you might think. Indeed, we are just beginning to enjoy ourselves and will be sorry to leave here. On Tuesday, a Bedouin funeral passed us. The women followed the coffin, shrieking and making a horrible noise and were waving their black robes and looking as weird as could be. Yesterday, we went to the Catacombs which have only been unearthed a few years. There are some very fine Egyptian and Roman carvings in good preservation and the bones still lie in the places hewn out for them."

By mid January, there were fears that the Turkish Army would attempt to seize the Suez Canal and invade Egypt. The Manchesters were sent to Cairo to shore up the defences of the city. The attack came on 3 February but was repulsed by Indian Army units and Tom did not have to go into action.

February was a significant month of this story. It's believed that, early in his service, Tom's friend, Alexander Milne, had been selected to become an officer and, during the month, he received his commission as a Second Lieutenant. Alexander would not join the Battalion until 25 April

Also during February, another young man received a commission into the 22nd Battalion of the Manchester Regiment. This was the seventh of the "Pals" Battalions which had been formed in the autumn of 1914 but which wouldn't go into action until the November 1915. He was Thomas Ryland Worthington and came from nearby Alderley Edge. Although he and Tom may never have met, he has an important part to play later in this account.

For the next few weeks, life for the soldiers continued much as had been in the previous ones. Rumours continued to fly round the camp that they would soon be called on to go into action. They hoped to go back to Belgium or France - where the "real war" was. But, on 28 April, orders were received by the Divisional Commander that the Division must be prepared to move to the Dardanelles at short notice. The Divisional History recounts "The news soon spread; it was no rumour this time, but the real thing, and on April 30 excitement was at fever heat. At last the Territorials were to be given the opportunity to which all ranks had looked forward so eagerly and toward which recent training had been directed. Little time was given for preparation, but no more was needed, as the Division was ready to take the field."

Gallipoli

On 3 May, the Manchesters boarded the Derflinger. This was a captured German vessel which had only arrived in Alexandria a few hours before carrying over 500 casualties from the fighting. It will have been a sobering experience for Tom and his comrades as stretchers, bloody bandages and clothing still littered the decks. They landed at Cape Helles on 6 May, at "V" and "W" beaches, assembling with the other battalions of the Manchester Brigade (127th Brigade) on the cliffs between the two landing beaches, at a point known as Shrapnel Valley. Each man carried 200 rounds of ammunition, 2 days supplies of food, together with picks or shovels. No baggage, blankets or other stores were carried with them. The Battalion comprised 32 officers and 937 men.

From this date, the Battalion maintained a War Diary. This was written up, usually daily, and briefly detailed the events. The original is held at the National Archives. It is written on flimsy pages from a notebook. The writing is now faded and difficult to read, but it is possible to make out that on 9 May, the Battalion suffered its first casualty. The men were in reserve trenches but under attack from shellfire. At about 10am, part of the trench collapsed, no doubt from the earlier shell damage. Private Murray Blaikie was killed. His death is recorded as "accidental". He was buried the next day but, over the course of the war, the location of his grave was lost and he is now commemorated on the Helles Memorial to the Missing.

6th Manchesters in Krithia NullaOn 11 May, the Battalion took over a section of the front line for the first time, in the Krithia Nullah sector. It would now suffer casualties on a regular basis, from shrapnel or sniper fire. Supplies were also a constant problem. There was never enough water. Never enough food. And never enough firewood to cook food and brew tea. It was not uncommon to see stores stacked on the side of trackways, so the packing cases could be used for fuel. This tour of duty lasted until 21 May, when they moved back to the reserve lines.

On the 25th, they were back in the front line. In the days they had been away, the line had been advanced by 50 yards. There was a massive cloudburst and, within minutes, the trenches were flooded. Across the battle field, there were several deaths - men forgot where they were and, in a desperate attempt to avoid the waters, jumped out of their trenches only to be shot by snipers.

Between 27 and 29 May, an advance of approximately 200 yards was made to bring the British front line within charging distance of the Turkish positions. This was carried out by the men crawling out into No Man's Land during the two nights. Each carried a shovel and two sandbags which he sheltered behind. Each dug a hole to stand in, 5 paces from the next man and the holes were then linked up to form a trench.

Zaccheus Holme described this in his last letter to his mother on 31 May (he was killed in the forthcoming attack on 4 June). He lived in nearby Cheadle Hulme and worked at a bank in Manchester. He and Tom would almost certainly have known each other.

"We are now in the firing line again and have been here now for six days, after having only four days in the rest trenches after our last spell in the firing line, so that for nearly three weeks, we have only had four days rest. We have been a night knee-deep in mud and water as the trenches were in a terrible condition, owing to a severe storm in the afternoon. On Wednesday night, we advanced 100 yards. We left the trenches we were in and advanced in the open at 9.45pm and, for the rest of the night, we had to dig in as hard as we could to get cover. Most of it had to be done lying flat and, I can tell you, it was awful work, but luckily for us the enemy did not spot us and we only got a few shots, but nobody in the company was hit. If we had been seen, it would have been frightful. The advance was quite a success as we were able to get the new firing trench dug and also the communicating trench to it. I can honestly say I have never worked harder before in my life as we were digging for seven solid hours."

Orders were then issued for the attack on 4 June (this would become known as the Third Battle of Krithia). From 8am, there would be an intense bombardment of the enemy trenches. Private R Sheldon, "C" Company, later described the morning "Shells in thousands were dropped, blowing part of the Turkish trenches to atoms and completely blowing away the barbed wire entanglements. Every shell that dropped seemed to tell - for we saw, hurled up into the air - legs, arms, heads, bodies, parts of limbs. It was an awful and fearful sight."

![[Image]](pict418.jpg)

The plan was that at 11.20am, all the guns would fall silent and the infantry would cheer as though about to attack. It was hoped that this would lure the Turks into manning their front line which would then be bombarded again. The real attack would then take place. Half the battalion would be in the first wave, ordered to take the enemy front line trench. The other half would be in the second wave following 15 minutes later.

The plan worked! As the men began to cheer and fire their rifles, the Turks opened fire with machine guns. Moments later, the barrage started up again, killing many of them.

The 4th June Attack

an original photograph of the attack, taken from the Regimental ArchivesAt noon, the leading platoons of Manchesters ("A" Company and half each of "B" & "D") left the protection of their trenches and charged across the 200 yards of No Man's Land in good order. They were hit by devastating rifle and machine gun fire. Within 5 minutes, they were in the Turkish front line and were engaged in fierce hand-to-hand fighting. As they secured the trench, the other half of the 6th Manchesters ("C" Company and the other platoons of "B" & "D") overlapped them to take the Turkish support trench. The attack of the 5th, 7th and 8th Manchesters had also gone well. However, units on either side of the Manchester Brigade had been less successful. The Turks were now on three sides of the Brigade and, by mid-afternoon, it was becoming impossible to hold the position. An order for withdrawal back to the original Turkish front line was ordered at 6.30pm,

770 men of the 6th Manchesters had gone into action. By nightfall, when the roll was called, only 160 were fit enough to answer. 48 men had been killed. Tom and Alexander Milne are believed to have been members of "C" Company. It had been virtually wiped out but, as far as is known, the two friends had come through unscathed. The Battalion would be in the firing line for three more days before it was relieved and would suffer another 100 deaths.

On 7 July, the Battalion's Commanding Officer received a letter from Major General Douglas "I am still hoping that you may be able to collect evidence of some of the special acts of gallantry by officers and men of your battalion during the assault on 4 June. It is most unfortunate that, owing to the many casualties you sustained, many deeds worthy of the Victoria Cross, have not been reported. I hope that your men know this. The dash, steadiness, reckless bravery and endurance shown by the 6th Manchester and, indeed, by the whole Brigade, was equal to the best traditions of the British Army."

After withdrawal from the front line, the Battalion spent a few days in the reserve lines before being withdrawn, on the 12th, to the island of Imbros for rest and refitting. Of the 770 men who had gone into action, only 288 were still left. During this period, they received some reinforcements and were back at Gallipoli on 22 June.

At some point, Tom received a minor shrapnel wound and, whilst on his way to the dressing station, he found the Company Sergeant Major wounded in the head. He attended to him and managed to carry him on his back, even though the CSM was a man of 6 feet 4 inches, to the dressing station. Tom returned to the firing line an hour later. This was possibly on 13 July, when the War Diary reports that two sergeants received head wounds, one fatally. The Stockport Advertiser later reported that, only a few hours after, Tom's officer was killed and he had to take charge of the platoon (although this is not supported by the War Diary, which makes no mention of the death of any officer around this time).

(Note: Since this article was first published , a reader has recognised the CSM, from his height and nature of his wounds, as being his grandfather. "C" Company CSM John Hurdley was badly wounded in the attack on 4 June and was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his bravery. The citation reads "For conspicuous gallantry on 4th June, 1915, on the Gallipoli Peninsula.During an assault he was wounded in the head and partly paralysed, but refused to be taken to the rear, and continued to give orders and rally scattered parties in the Krithia Nullah. - It was largely due to his brave conduct that the advanced line was held."

It was, no doubt, later in the day that John must have made his way back to the relative safety of the British line where he was found by Tom. It is probable that Tom's action may have saved John's life. He recovered but was never fit enough to return to duty. His skull was mended with a metal plate and, for the rest of his life, he had to wear a calliper to support his left foot as a result of the brain damage. He became a leading light in the Boy Scouts movement in Greater Manchester. On his retirement, he became ordained as an Anglican minister and died, at the age of 83, in 1959. He had also been awarded the Russian Cross of St George (2nd Class) for his bravery - one of only a handful of British soldiers to receive the medal. John was also "Mentioned in Despatches" for his good service at Gallipoli.

As mentioned above, Tom will have taken command of his platoon on 4 June, after the officer was killed.)

It would seem that, by now, Tom had received a temporary promotion to Company Sergeant Major, no doubt taking over from his wounded comrade. He was also selected to become an officer and was due to be discharged to a commission on 12 August. It was not to happen.

On 6 August, the 5th Manchesters took part in an unsuccessful attack and, the next day, it was the turn of the 6th Battalion to try again. The attack would become known as the Battle of the Vineyard. The troops were in position by 7am. The Turkish Army was obviously prepared for another assault and was shelling the British position. The Battalion War Diary notes that "even before the first assault, we had a good many casualties in the trenches". Leading the attack would be "C" Company, including Tom and Alexander Milne (recently promoted to Lieutenant). At 9.40, they left the trench and reached the Turkish front line, some 70 yards away. There were many casualties - some had got no more than 20 yards before being mown down by machine gun fire. Private F Ollerenshaw, "C" Company, described it in a letter published in the Stockport Advertiser "We were all ready on the ladders and steps and, when the word came, we went up together and ran as fast as we could"

Fierce fighting took place in the Turkish trench and the War Diary records that "Lieut Milne fired 4 shots with his revolver into a redoubt where they were bombing our men and was then shot in the head". Pte Ollerenshaw wrote (probably referring to Alexander Milne)" We had only one officer left by this time and as we were being bombed from the sap on the left and the trench was being searched by shrapnel, it became imperative that we should move. The officer jumped up onto the top of the trench but was immediately hit and fell back. Then a few of us tried to get over but another burst of shrapnel came and about three were left standing. The man next to me was killed outright, shot in the head." The War Diary later recorded "CSM Worthington badly wounded in trench - now missing".

By now, "B" and "D" Companies had also advanced but were subject to heavy fire and very few managed to join the men of "C" Company. Battalion Headquarters, in the British trench, was hampered as it could not properly see what was happening, due to the smoke and dust caused by shellfire. By 11am, it was very clear that the Turkish positions were strongly held and were being re-inforced still further. A few minutes later, the troops were driven out of the trenches they had captured and were forced back to their starting point, by 11.15. At 11.55, they were ordered forward again, but it was quickly realised that it was an impossible task and the orders were cancelled 5 minutes later. Over 140 men of the 6th Manchesters were noted as being dead, wounded or missing (later records confirm that over 75 had been killed)

Tom was never seen again. His body must have been buried by the Turkish troops but, in the heat of battle, few records were kept or attempts made to identify the dead. After the War, his body was never recovered and identified. Nor was that of his friend, Alexander Milne. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission records the names of some 27000 British and ANZAC troops who died at Gallipoli and have no known grave. Of these, nearly 12000 are buried in War Grave Cemeteries with headstones marked only "Known unto God". The remaining 15000 are still "out there somewhere" waiting to be found. Bodies are discovered to this day.

Four days after Tom had been posted as missing, the London Gazette appeared. It included the official notice that Sergeant Thomas Roughton Worthington was to be commissioned as a Second Lieutenant into the 6th Battalion, Manchester Regiment with effect from the next day, 12 August.

But this is not the end of the story.

What Happened Next

It took a little while for news of Tom to reach Cheadle. In fact, the Stockport Advertiser, in its edition of 27 August, was only reporting Tom's commission. However, a week later, it reported that the Army Record Office at Preston had advised that Tom had been missing since 7 August. On 1 October, the Advertiser reported "For some time rumours have spread through the village that Lieut. Tom Worthington, of Cheadle, had been killed in action, although the War Office has stated he was "missing". An officer of the same company, writing home this week, says "Most certainly Lieut T Worthington fell in action. He was next to me when he was killed".

The war would continue for more than three years. 101 men from the village did not come back. It is difficult now to imagine the grief that must have been a constant factor in the lives of many families. The Lee and Wrench families each lost three sons. An advert in the Stockport Advertiser of 2nd April 1920 announced the establishment of a war memorial fund and invited the submission of names for inclusion and donations towards the cost of construction. By October, drawings of the proposed structure went on public display and residents were asked to confirm the spelling of names to be inscribed. The memorial was unveiled in September 1921. Its inscription reads "To the Glory of God and in grateful remembrance of the men of this village who fell in the great war 1914 - 1919."

Life in Cheadle started to return to normal until 1939, when war with German was again declared. About 10pm on 4 February 1941, a lone German bomber was heading east from Stockport. Whether it was chance or it aimed its last bomb at the "Boundary Bridge" area cannot be known. Certainly, it would have looked a good target - two factories near a railway line bridge, which crossed a major trunk road. The bomb missed the factories by about 100 yards, landing in the back of 245 Stockport Road. In the dining room, Tom's sister Agnes Roughton Bennison, aged 62 and her daughter, Kathleen, 27, were sat knitting. You may remember them from much earlier in this account. They had the 'flu and had decided to stay by the fire rather go to the air raid shelter in the back garden. As the bomb exploded, it blew in the back wall of the house, decapitating both women. Mrs Bennison's husband, Walter, was one of the "fire watchers" out on duty that night and had to be restrained from going into the house.

When the War ended, the people of the village added two more plates to their War Memorial. One commemorated the 51 service men and women who had died during the war. The other, including Agnes and Kathleen, remembered eight villagers who had been killed in two air raids.

The village has been fortunate in recent years and no new names have been added to it from the conflicts since World War 2. And, in terms of this story, nothing else happened until 2002. That year, I developed a new interest in local history and decided to find out what I could about the men on my local war memorials.

I quickly realised that there was something different about Tom Worthington. Unlike all the others who had been killed, he was not officially commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. I decided to try to rectify that. I knew that the Commission required a heavy burden of proof, but I was able to assemble all the information that I've used to tell the above story - including extracts from the 1901 Census, the newspaper cuttings, his medal entitlement records from the National Archives (which confirm him to be missing), the War Diary and several other pieces of information. In early 2004, I sent all this to the Commission and sat back and waited. And waited. And waited some more.

This gave me plenty of time to wonder how Tom had come to be missed off the records. Although no-one can know for sure, it has been estimated that perhaps between 10,000 and 20,000 men who died as a result of their war service have no official commemoration. For most, it's because they died after being discharged from the army and no-one passed on the information. But I think the reason for Tom being missed off is good old simple clerical error. I am convinced that, in August 1915, Tom's official paperwork was in the process of being transferred to a metaphorical "officers filing cabinet" from the "other ranks filing cabinet". It would mean he never appeared on an official list of officers killed (as he was never actually an officer), nor did he appear on that of the "other ranks" (as records were showing he was discharged to a commission).

In 1920, another announcement appeared in the London Gazette, cancelling the entry of August 1915. Officialdom had realised that Tom Worthington never became an officer on 12 August as, by then, he was already dead. His medal records support this as the original entry records him being "discharged to a commission" and this was not amended to "missing" until 1922.

In early 2005, I received a reply from the Commission. The Ministry of Defence was prepared to accept T R Worthington as a casualty. Although to my dismay, the man they wanted to accept was a man I, and the Commission, knew was not Tom. They wanted to accept the man I mentioned very early in this account - Thomas Ryland Worthington. I already knew of him (and had been able to easily discount him from my research many months before - frankly, I was surprised that the Ministry had not also discounted him).

It was easy to find the evidence that the men were two separate individuals and could not reasonably be mistaken for each other - the other Thomas Worthington was commissioned in February 1915 and didn't go overseas until the autumn. He was brave man, winning the Military Cross with the 22nd Manchesters. He survived the War and returned home to Alderley Edge, where he continued a successful business career in Manchester until he died in 1949.

Needless to say, I asked the Commission to resubmit the information on Tom to the Ministry. Throughout 2005, I tried to get progress information but I couldn't even get an acknowledgement from the Commission, let alone a proper response. Determined to reach a conclusion, I decided on a different tack. I wrote to my MP, Mark Hunter, in February 2006, enclosing all the evidence and asking him to take up the matter with both the Commission and the Ministry. He agreed to do so.

Within days, the matter was resolved. On 21 February, the War Graves Commission wrote saying that Tom was to be commemorated. His name will be included in the Debt of Honour Register and, in due course, it will be inscribed on the Memorial to the Missing that stands at Cape Helles on the Gallipoli peninsula. After 90 years, Tom is "in from the cold"; his service to his country recognised along with those of his mates.

To contact the author of this article, email John Hartley

![]()

Copyright © John Hartley,

February, 2006

Copyright © John Hartley,

February, 2006

Return to the Hellfire Corner Contents Section