![]() TOM MORGAN

TOM MORGAN

![]()

In Flanders stands the ancient town of Ypres. Once a centre of the flanders wool trade, it became one of the most important European city-states of the 13th Century. In 1260, Ypres had a population of some 40,000 - more than the population today. At the same time another great city, Oxford in England, had a population of only 4,200.

The area has been fought over, through the centuries by the Dutch, the French, the Spanish - no wonder that the area was called "The Cockpit of Europe." But it was the Great War which resulted in the destruction of the town, and the loss of its priceless mediaeval architecture.

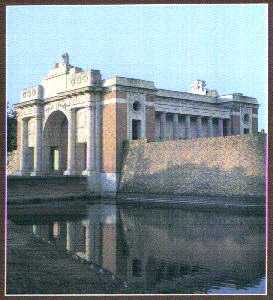

The Menin Gate Memorial is perhaps the most visited Great War Memorial on the Western Front.

The original Menin Gate marked the start of one of the main roads out of Ypres towards the front line and tens of thousands of men must have passed through it and onwards along the infamous Menin Road, so many of them never to return.

There was a particularly corny joke in vogue in 1917 - "Tell the last

man in the line to close the Menin Gate." However, there was no actual gate,

nor even an arch.

Instead, there

was simply a gap in the ramparts which almost encircle Ypres, and a bridge

across the moat. There had been a gate once, as part of the original

fortifications, but this had been demolished long before the war, to

widen the road into the town. In the accompanying photograph, a line

of wagons can be seen passing through the "gate" and the ramparts on one

side are clearly visible as a bank with some shattered trees growing on the

top. The soldiers sitting around their brazier in the snow are just outside

the ramparts and the wagons are leaving the town. This photograph was taken

in 1917. The Ramparts of Ypres were designed by the French military Architect,

Vauban. The star-shaped layout of the defences, with their surrounding moats

and canals, is typical of his work. Ypres had been a fortified town for centuries

before Vauban came onto the scene, however, and the earliest fortifications

were built in the 14th century by the Burgundians.

Instead, there

was simply a gap in the ramparts which almost encircle Ypres, and a bridge

across the moat. There had been a gate once, as part of the original

fortifications, but this had been demolished long before the war, to

widen the road into the town. In the accompanying photograph, a line

of wagons can be seen passing through the "gate" and the ramparts on one

side are clearly visible as a bank with some shattered trees growing on the

top. The soldiers sitting around their brazier in the snow are just outside

the ramparts and the wagons are leaving the town. This photograph was taken

in 1917. The Ramparts of Ypres were designed by the French military Architect,

Vauban. The star-shaped layout of the defences, with their surrounding moats

and canals, is typical of his work. Ypres had been a fortified town for centuries

before Vauban came onto the scene, however, and the earliest fortifications

were built in the 14th century by the Burgundians.

These fortifications, though, belonged to a different era. When the War came to Ypres in 1914, they could not stop the heavy shells which were fired into the town, reducing it to rubble by the time the war ended.

Almost as soon as the war was over, there were plans to build some kind of memorial in the Ypres area. One plan considered by the British Government involved the purchase of the entire ruins of Ypres, with a view to turning the whole town into a memorial to the British and Empire participation in the war. For the citizens, though, the ruins were still their home-town and they wished to return. The Belgian Government offered two sites to the British for their use as memorials - the ruined Cloth Hall and the Menin Gate site. There was a change of mind about the Cloth Hall following a decision to rebuild it just as it was before the war (this work was finished in 1964) and so the British Government began to plan a Memorial at the Menin Gate and decided that it should commemorate the Missing - those members of the British and Empire armies who had died in the fighting around Ypres, but who had no known graves.

The memorial was designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield and was built in the face of considerable construction difficulties. It was opened in 1927, ten years after the terrible Third Battle of Ypres - the beginning of the campaign which ended with the capture of the village of Passchendaele by Canadian troops.

Blomfield's memorial combines the architectural images of a classical victory arch and a mausoleum and it contains, inside and out, huge panels into which are carved the names of the 54,896 officers and men of the commonwealth forces who died in the Ypres Salient area and who have no known graves. This figure, however, does not represent all of the missing from this area. It was found that the Menin Gate, immense though it is, was not large enough to hold the names of all the missing. The names recorded on the gate's panels are those of men who died in the area between the outbreak of the war in 1914 and 15th August, 1917. The names of a further 34,984 of the missing - those who died between 16th August, 1917 and the end of the war, are recorded on carved panels at Tyne Cot Cemetery, on the slopes just below Passchendaele. There is an exception to every rule, of course. The Menin Gate bears the names of all the Australian and Canadian Missing from the whole of Belgium, regardless of date.

The Menin Gate is not a memorial tucked away in some remote part of the town, remembered now and then. The Menin Road is still an important thoroughfare and traffic and pedestrians pass under the gate as part of the daily life of Ypres. In this aspect alone, Remembrance is kept very much alive in Ypres, but there is more.

Every night of the year, without exception, policemen close the road to traffic at 8.00 p.m. while buglers from the Last Post Association play "The Last Post". This happens whatever the weather and there is always someone there to watch and remember during this daily act of Remembrance carried out on behalf of the people of Ypres in honour of the young and brave who came from all over the world to die in the defence of their town.

What used to be a quiet, local ceremony with few outside visitors has grown into an internationally famous event these days. As the numbers of people visiting the battlefields have increased, so have the numbers attending. During the summer battlefield-tour months, there may be many hundreds of visitors there. On really significant days such as November 11th, the Last Post Ceremony will take place at 11.00 a.m. as well as 8.00 p.m. and there will be large parades with thousands present. The nightly event is a moving one no matter how many people are there and would still take place even if no-one was there at all, though there's no danger of this any more. The ceremony has taken place almost continuously since 1927. During the Second World War, when the Germans occupied Ypres, Last Post was banned - not out of any lack of respect for the dead, but as part of a general ban on large gatherings of citizens. The bugles were kept safe, however, and when the Germans left Ypres on 6th September, 1944, the plaintive notes of the Last Post rang out under the Menin Gate that same evening.

Part of the speech of Lord Plumer of Messines

at the unveiling of the Menin Gate, 1927

"One of the most tragic features of the Great War was the number of casualties reported as, 'missing, believed killed'.

.............. when peace came, and the last ray of hope had been extinguished, the void seemed deeper and the outlook more forlorn for those who had no grave to visit, no place where they could lay tokens of loving remembrance.......

...........and it was resolved that here at Ypres, where so many of the missing are known to have fallen, there should be erected a memorial worthy of them which should give expression to the nation's gratitude for their sacrifice and their sympathy with those who mourned them. A memorial has been erected which, in its simple grandeur, fulfils this object, and now it can be said of each one in whose honour we are assembled here today:

He is not missing; he is here!"

If you'd like to know more about the "Last Post" ceremony,

please visit the Last Post

Association web-site.

![]()

Copyright © Tom Morgan,

November,1996 - January, 2014

Copyright © Tom Morgan,

November,1996 - January, 2014

Return to the Hellfire Corner Contents Section