![]() MARTIN MIDDLEBROOK

MARTIN MIDDLEBROOK

![]()

Introductory Note

I have always been a fan

of Martin Middlebrook's book, "The First Day on the Somme".

When I bought my first copy - over 40 years ago now - it

gripped my attention from the first page and it is the only book that

I have ever read from start to finish, in one go. I stayed up

all night to do it. That was in 1971. In 2004 I heard that

Martin Middlebrook was to retire from writing and guiding, so I wrote

to him to ask if he would tell me the story behind the writing of the

book. After all, I thought, a book which has made such an

impression as this one must have a history of its own, and I would

like to know it. Martin Middlebrook's answer to my question

eventually took written form, and I'm very grateful to him for

allowing me to publish it here, so that others can read the story for

themselves.

Tom Morgan

It started in September 1967. I was thirty-five years old, a businessman, a family man with three daughters, living in the town of Boston, Lincolnshire.

My father and his brother were both too young to have served in the First World War. My mother was only eleven years old in 1914, the youngest of six children. In my own childhood she told me many stories of the deep effect the war had on her family.

Her eldest sister, my Aunt ‘Ettie’, was in Belgium when war broke out, working as governess to the daughter of a wealthy family at Mons. She was trapped in Belgium, under strict German supervision for most of the war, an anxious period for her family with another English lady in Belgium at that time, Edith Cavell, being executed by the Germans.

Her eldest brother, my Uncle Andrew, was a pre-war Territorial who went to Belgium in March 1915 as a Platoon Sergeant in the 4th Lincolns, was severely wounded in the stomach by a ‘whizz-bang’ near Armagh Wood in early October 1915, and died a few days later at Remi Farm near Poperinge. He is buried in Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery.

A second, brother, Uncle ‘Charlie’, joined up in Kitchener’s Army, serving in the 8th Gloucesters, 19th (Western) Division until he was captured in the March Offensive in 1918. He was slightly gassed at the time of his capture, which did not prevent the Germans from putting him to work in a coalmine. He is said to have thrown his medals away as a protest at the neglect of the 1914-18 servicemen after the war. He died from the chronic bronchitis that his touch of gas in March 1918 had given him.

At the same time that all this was happening, my grandfather died in a failed surgical operation. The First World War was a very sad period for my mother.

This introduction illustrates how a youngster born in 1932 became so intrigued by the First World War while living right through the Second. As a boy I was an avid reader of war books and stories in comics. Who remembers ‘Biggles’ (Captain Bigglesworth, RFC) and ‘Rockfist Rogan RAF’; was it in the Hotspur that the latter performed his heroics? Later I read most of the First World War books published in the 1960s but, while they gave me a good working knowledge of the progress of the war, they seemed to describe little more than the decisions of generals and the movements and actions of units no smaller than divisions; they contained little of the experiences of the ordinary soldiers.

I later found two books that were more enlightening on those aspects. They were The General by C. S. Forester, published in 1936, and Covenant with Death by John Harris who had interviewed men from his native Sheffield’s City Battalion of Kitchener’s Army and whose book appeared in 1961. But these books were fiction. Did they reliably portray the factual background? I came to accept that not only were the underlying stories accurately told, but they brilliantly portrayed their respective views of the war – the one looking at the conflict from the top looking down and the other from the bottom looking up. I have never deviated from the view that these are the two best books on the First World War and would recommend them to any newcomer wishing to start their study of that war.

I left school at the age of seventeen after a sound basic education. It was my own choice to leave; I was not naturally academic. I went to work in my father’s wholesale potato merchant business. I did my National Service, escaping being sent to Korea as a private soldier in the Leicesters because of my colour-blindness, and became a Second Lieutenant in the RASC. I was posted to the Middle East, becoming a Transport Platoon Commander, first at Aquaba in the Jordan (Lawrence of Arabia country) and then in the Suez Canal Zone in Egypt (boring). I never heard a shot fired in anger.

My undistinguished National Service did, however, give me a benefit that was later to prove most useful. I found that I enjoyed studying the organisation of the Army. I could lecture on the exact composition of an Infantry Division without referring to notes. Any new author attempting to write a war book is faced with the complicated nomenclature of military writing – not just the detailed organisation of units but such minutiae of when to use capital letters and when not (most beginners use too many), the subtle difference between such things as a Commanding Officer and an Officer Commanding, etc, etc.

Nothing much of relevance happened in the next fifteen years. I married a Boston girl. We bought a house in the town that had some sheds in the back garden. I bought six pullet chickens to provide us with eggs. I became a full-time poultry farmer. By 1967 we had three daughters of school age and my poultry business was so well established that I could spare the time to take short breaks from it.

How About A Trip To The Battlefields?

I had, and still have, a good friend, John Howlett. He also had strong family links to the First World War. His mother, a Manchester-born lady, had lost her fiancée. He was Private Harry McLinden, 17th Manchesters (2nd Manchester Pals). He took part in the first day of the 1916 Somme battle but was killed on 22nd April 1917 at Héninel near Arras. He has no known grave. The bereaved lady became a nurse at Southport Royal Infirmary where she nursed Private George Howlett, from Hull, who had been twice wounded while serving in the East Yorkshires – 8th and 7th Battalions. The nurse married George Howlett and my friend was part of their family brought up in Hull.

John and I soon discovered our common interest in the First World War and would love to visit the battlefields. In September 1967, after our children had returned to primary school following the summer holidays and before John’s term as a Lecturer at the local College of Further Education started, we made the trip.

We set off in my Morris 1100. We ‘did’ Verdun, the Somme, Arras and Ypres, with a side visit to Mailly-le-Camp where a close friend of my family, a Lancaster navigator, had been shot down in May 1944. I think we had just five days for the whole journey. There were no motorways between Boston and Dover (200 miles) or between Calais and Verdun. We had no guidebooks, only a series of place names that were known to us from our reading of war books, although I did know where my uncle Andrew was buried and John knew approximately where Harry McLinden had been killed.

We crossed the Channel and reached Arras in the evening. We treated ourselves to dinner at the Restaurant des Arcades overlooking the Grande Place. I experienced a magical feeling. Here we were, on one of the most famous places of the Western Front, dining at that atmospheric spot. I have been to Arras many times since and always try to go back there for a meal or a drink in the evening.

We continued our journey through the first part of the night to Verdun. The feeling of magic continued. We passed signposts to places made famous in the two world wars. We drove along roads on which I imagined that German Panzers had swept through in 1940. In the early hours we stopped and slept a few hours in the car parked on a track by a canal. Next morning, we brewed up, had a shave (that is John in the photograph), went into Verdun and had breakfast. We spent the rest of the day on the Verdun battlefield visiting the obvious places – Fort Douamont, the Ossuary, the Trench of Bayonets and the lost village of Fleury. The Museum at Fleury had not been built then; I was thrilled to find a complete French rifle cartridge in the village ruins.

We went on to complete the full programme but in the most sketchy and haphazard of ways. John found a cemetery near Héninel where there were six graves marked as unidentified Manchesters; there was strong evidence that one of them was Harry McLinden’s. I visited the graves of the Lancaster navigator and of my uncle at Poperinge. I do not remember seeing any other British visitors during the tour.

The Effects Of The Tour

Although my family interest was unconnected with the Somme, it was this part of the tour that left me deeply and emotionally impressed – the open nature of the battlefield, not only the large number of cemeteries but their constantly varying sizes and designs, the large number of unidentified graves, the sheer number of dead in such a small area of ground. I had imagined that The Battle of the Somme was a sweeping affair over a large area of ground. I was amazed that we could drive from La Boisselle to the Butte of Warlencourt in just a few minutes.

We had approached Albert, where we intended to spend two nights, from the direction of Péronne. On the way in we visited the Gordon Cemetery and then the Devonshire Cemetery. Virtually every headstone was marked as ‘1st July 1916’. I was particularly moved to find myself looking at the graves of six Gordons’ subalterns buried together in the corner of their cemetery. I had spent a year of my National Service in the close company of fellow subalterns and could hardly visualise the sadness of having six comrades killed in one morning.

Moving on to other cemeteries next day, we saw the date ‘1st July 1916’ many more times. I think that no one can realise the scale of the disaster that day until they have seen the cemeteries in which the men killed that day are buried.

We returned home. There was one amusing sequel. We had found various souvenirs and kept them in a bag. After a few days showing them to my friends, the bag went to John’s house. One day a scrap merchant came looking for unwanted items. The cleaning lady gave the entire collection to him.

That was the only light note. I told everyone who would listen about the tour. I scraped some dried Somme mud from my walking shoes and regarded it almost as a religious relic. Whatever happened in my future life, that visit to the Somme would be a turning point. To find out more became an obsession.

‘I’m Going To Write A Book About The Somme’

The following winter passed otherwise uneventfully. Then, in April 1968, I decided to re-read John Harris’s Covenant with Death. Most of my reading is done in bed at night. I can remember clearly closing the last page and saying to my wife, ‘I’m going to write a book about the Somme, through the eyes of the ordinary soldiers.’ The primary reason for this declaration was not that I had any hope of the book being published but that, if I said I was writing a book, I would have an acceptable reason for approaching the sources of research and the men who were in the battle. I soon refined my exact approach. Where John Harris had written a fictionalised version of the experiences of one battalion, I would cover just the first day of the Somme but cover all of the British units that took part. The possibility of covering the German side was nowhere remotely in that early plan.

|

|

I have to explain at this point that a year earlier I had been elected a member of the British Egg Marketing Board and I attended meetings in London about twice a month, with First Class rail travel and overnight hotel expenses provided. Those benefits would prove to be valuable assets. Very soon after my bedtime decision I was in the train to London and took out a large plan of an Egg Exhibition due to be held at Leicester. On the back I made a list of headings for my proposed book. (I kept the plan for many years but cannot lay my hands on it now.) I already had a very clear and simple title: The First Day on the Somme. I have never regretted that choice. |

The first doubt crept in. I had left school at seventeen and had written nothing longer than a business letter for nearly twenty years. How could I write a book? I went to my friend John Howlett – a University Graduate, a College Lecturer. Would he like to join me? I had the time and opportunity to do the research; he would do the writing but we would share the credits if the book ever came to be published. John was enthusiastic and agreed. We even had some letterheads printed with THE FIRST DAY ON THE SOMME emblazoned across the top and with both of our names and addresses.

The Research

I set to work on my share of the work. On my next visit to London I went to the Imperial War Museum, stated that I wanted to research a book and ‘Please, can you help?’ The answer is well remembered, ‘You had better see our Miss Coombs’.

I was shown into her office. Sitting at her untidy desk was a dumpy lady, smoking. But she had a nice smile and was both patient and helpful. She told me two things that set immediately set me on the right path: that I should concentrate on research from ‘original sources’ (an unknown phrase to a poultry farmer), and that the best place for this was the Public Record Office (equally unknown). Before parting she said she would give me a final piece of advice: ‘When you have so much good material that it is breaking your heart that you can’t find room for it all, you might, just might, succeed in writing your book’.

I did not realise at the time that it was my first meeting with a lady who would become one of the most respected and knowledgeable of Western Front enthusiasts. Such people numbered only a handful at that time. I was to count her as a close friend and helper for the rest of her life that was ended prematurely by her addiction to tobacco – but she did enjoy life and gave great pleasure to all who knew her.

There now occurred a combination of circumstances that proved to be so fortunate to my objective. Under the ‘Fifty-Year Rule’, the official documents of the First World War period had just been released at the Public Record Office; few researchers had as yet touched them. Furthermore, in those days the PRO was located in Chancery Lane, a short distance from my regular hotel in London and from the Egg Marketing Board offices. Board meetings started at 10.00am. The first train from Boston did not reach London until just after that time. I had been told that I was to travel the previous day, stay the night in a hotel, and be on time for meetings. I found that, by catching the first train from Boston on Day One, I could be in the Public Record Office by 10.30am and work there until closing time. The Egg Board meeting on Day Two was usually concluded by lunchtime. A further afternoon’s research followed and then the train home to Boston.

In this way I managed a day and a half’s research in Rose Coombs’s ‘original sources’ at no expense to myself and with no extra travelling involved. I found that there were bulky files on every formation from GHQ, through Fourth Army, then Corps, Divisions and Brigades down to Battalion level. I will not pretend that I looked at every file. The Official History was based on many of those files so, after looking at the higher levels of command, the only need was to investigate individual points as they arose.

Enter onto the scene one Patrick Mahoney. I had started to seek out men who had been involved in ‘the first day’ and the London Evening News was one of many local newspapers that published my appeals. I think it was published in London on a Friday evening. That evening a man called Patrick Mahoney telephoned to say that he was very interested in the First World War and how could he help? He arrived on my doorstep next morning. Patrick was a bachelor, living at Chadwell Heath in Essex, and worked permanent night shifts in the Post Office’s International Telegraph Department. He needed little sleep at home (he slept quite a lot at work when telegraph traffic was quiet); his days were free and he knew where the Public Record Office was. I sent him there with my next list of tasks.

Patrick turned out to be a brilliant researcher and took over most of my PRO work. Not only did he see to all my requests but also, by trawling various files that I would not have had time for, he frequently found interesting items that I would not have discovered. For the next two years he carried out any task in London that I requested. The only recompense that he asked for was that I would one day take him to the Somme. We will meet Patrick later in this story but I can mention here that he carried on with my London research for later books until the Public Record Office moved to Kew.

The combination of Public Record Office and Official History research, together with the many published battalion histories, eventually gave me a more than satisfactory accumulation of original source material and, thus, a firm framework on which to base interviews with the participants of the battle. There was much that was new but, with two exceptions, there was nothing startling. I have always contended that, although The First Day on the Somme allowed a mass of soldiers to tell of their experiences for the first time, the book contains only two fresh contributions to military history.

The first came when I studied file WO95/447 at the PRO; it contained the Fourth Army’s Director of Medical Services documents. General Rawlinson had obviously insisted that the correspondence concerning the Ambulance Train failure be preserved. I later sent special ‘medical evacuation’ questionnaires to about 150 men who had been wounded on July the First, asking for the details of their experiences. The subsequent story is in pages 83-5, 197-8, 231-2, 249-50, and 299 of the book.

The second contribution was the disclosure that a copy of the so-called Rawlinson Diaries available to the public at an Army museum at Camberley was not the original version of his diaries. Patrick Mahoney went there on my behalf and advised me that I should examine the original in the archives of Churchill College, Cambridge. I did so and found that Rawlinson had revised many passages, putting himself in a better light, before releasing the typewritten version to public examination.

Obtaining The Soldiers’ Stories

A golden rule, that admittedly took more than one book to establish, is that contacting potential contributors should not start until all research is complete. For The First Day on the Somme there was some overlapping, but the following notes will assume that most research was complete at this stage.

I had always said that I would not be satisfied unless I could find at least a hundred men who had taken part in the attack on that first day on the Somme to obtain their personal contributions. Fortunately the only Empire infantry effort involved was the Newfoundland Regiment – just one battalion. As for any contribution from German soldiers, that would have to wait.

A dual policy evolved. Men who lived within a reasonable travelling distance from Boston, or in the course of journeys connected with my poultry business, would be seen personally, mainly by me because that was my part of the proposed division of work between John and myself at that time. For more distant men, I produced a carefully prepared questionnaire. On the front were basic questions about the man’s pre-war occupation, his date of enlistment and unit, questions about when he crossed to the Western Front, whether wounded or prisoner of war, date of release, post-war occupation. On the rear was just a simple question asking the man to write out at whatever length he wished what HE PERSONALLY had experienced in the immediate run-up to the battle and on the day itself. That questionnaire would have to suffice for men I could not reach for personal visits.

I sat down at the kitchen table and typed letters to newspapers, mainly to local ones. (The typing was done with one finger; 35 years later it is still one-fingered. I never did learn to type properly.) Each letter was tailored to the local involvement of an area. The nature of county regiment areas and particularly of the Kitchener Pals battalions made this easy.

The response was amazing. Approximately 500 men responded to that first round of appeals. I started interviewing. The first was Private H. Kemp of the Grimsby Chums. To me he was ‘Mister Kemp’ a dignified man who lived over the road from my childhood home in Boston. The crippled leg I had grown used to seeing had been earned in front of La Boisselle. His was the first of many vivid stories that would become available for the book.

I must generalise over the experience of visiting such men in the following year. It was fascinating to be able to talk to so many who had been there on that first day. I evolved a simple method of interviewing which, with almost no change, was to last me for the next 30 years.

Before asking any questions I spread out the appropriate corps map from the Official History and produced the relevant battalion file I had prepared. I checked his battalion, brigade and division, showed him where the battalion was on the map, told him the name of his battalion commander and, sometimes, of his company commander, and then gave a rough summary of what had happened to the battalion on that first day.

This initial procedure had several benefits. It screened out the occasional man who was not involved on July the First but who had contacted me out of curiosity or boredom or confusion; if that was the case I terminated the meeting as gracefully as possible. If the man was genuine, it told him that I was someone who had carried out the necessary preparatory work and this invariably gave him the confidence to share what might be an intimate and distressing story with someone who would use it in a responsible manner. I was also often able to tell him things he did not know or understand.

I have never used a tape recorder. I think that it makes the scene too formal; there is the risk that the man starts thinking about his answers instead of talking naturally. Also, I have occasionally been sent tapes by post and find that they take a huge amount of time to transcribe for the small amount of usable material, if any, that they contain. What I wanted from my meetings with the Somme men were specific stories of limited length that I knew I could use. I would chat to him as informally as possible until I reached the point where I needed something written. I would then ask him to tell that part of the story carefully while I scribbled it down as fast as I could. I developed a rough shorthand: NML was No Man's Land; BFLT or GFLT was the British or German front-line trench; there were many more.

The other technique I developed was always to sit at the end of my questioning and allow the man to chat on. He would often mention something that I had not thought of covering. Down it would go on paper. Finally, after I had packed my papers away, a man might express some deep, very personal, intimate thought that he assumed I would not need or use. What I did then was leave, drive away out of sight, park and record that last comment on paper. If I thought that the man would not object to seeing it in the book in the context of similar material, I used it; if not, it would be included but not under his name. When the book was published not one man complained that I had betrayed his confidence. (I did have three complaints. One man said I had not written enough about his division; a second, not enough about his battalion; the third, not enough about him!)

Over a period of about a year, I met about 100 of the men. As with my good fortune in having access to the recently released documents in the Public Record Office, I was lucky again to catch these men at just the right age – retired and with time to spare for daytime interviews (unlike many of the Second World War men I would meet in the next three books), and still young enough to have clear memories. I hesitate to use the term ‘veterans’ because I am now in my early seventies, the same age as the Somme men were at that time. From some of the men I met I gained very little, but from many there were the vivid stories you will see in the book. If I came away with no more than two or three paragraphs of usable material I was well satisfied.

The Postal Questionnaires

Meanwhile the postal questionnaire campaign was being waged to approximately 300 men who had offered their help: most of them were in the more distant parts of the country. It was a very simple and economical process – a friendly covering letter, the questionnaire and a stamped return envelope were all that was needed.

About 10 per cent of the men did not reply. The efforts of those that did varied enormously. Many contained little quotable material, but they did contribute to the steady build up of my ‘feel’ for the subject and they eventually gave the men who had taken part in the battle on that day an acknowledgement in the book which became a source of pride to him and his family. Other replies contained useful small items. If a contribution showed obvious potential for more material, I was sometimes able to include the man in a later interviewing tour.

But the big surprise was that there were a number of well-written contributions, extracts from which would form a major part of the book. These men were from a generation that had received a sound basic education and then often been employed in clerical positions that required the preparing of reports. I felt that they were ready, in their retirement, quietly to set down their experiences of what had been a traumatic episode in their lives for a stranger who seemed to have a serious interest in it. I had the feeling they were telling me things they had never spoken of before.

The Writing – A False Start

I had come to the end of my period of preparation – without any advice except that given to me at the outset by Rose Coombs, made up, often in muddled manner, as I went along. I had expended far more in effort and expense than I had ever imagined, but my poultry business subsidised both my time and expense. I had already fulfilled my first ambition, carrying out research and talking to the men who had taken part in that day, the graves of whose dead had so moved me on the visit to the Somme with John Howlett. He had been kept in touch with all the work so far and had actually done some interviewing in Manchester where his mother and her dead fiancée had lived. He declared himself ready to start writing once I had sorted the material into some sort of usable order.

I found the task of sorting the material ready for writing an enjoyable challenge but it would be tedious to go into detail. The notes for the first chapter – The Men – were handed over to John.

It seemed a tremendous setback at the time, but the whole basis of our partnership did not work. John did write the chapter but we both agreed at once that it was not a success. The reasons were not difficult to identify. I had carried out the research and nearly all the interviewing, and had become deeply immersed in the subject; I had a strong ‘feel’ for it. I had left my poultry business in the hands of a capable manager. By contrast, John was Head of a Department at a recently established local College of Further Education and his family of young children was larger than mine.

It was mutually agreed that John would not write the book. I must pay the greatest tribute to him that he accepted this disappointment without any resentment. If the original plan had worked, The First Day on the Somme would have been published showing it to be ‘by John Howlett and Martin Middlebrook’, with most of the public credit going to John. He has remained a close friend and loyal supporter of my work right up to the present day. He has also proved that he is far from being short of literary talent, having since written and produced a series of plays for young people.

I now found myself in a dilemma. I had a mass of material that I was confident could be turned into a book. Other people like John Howlett and Patrick Mahoney had also expended a lot of their time. About 400 old soldiers had trusted me with their memories and their hopes of seeing a publication. But I had no confidence in my ability to write a book; I had only said I would do so originally in order to gain access to research sources and talk to the men who had been on the Somme. I had written nothing longer than a business letter in more than twenty years.

I started to consider who did I know who was able to do the job and might be persuaded to give up an unknown quantity of spare time to write a book that might never be published? I thought seriously about a lady schoolteacher from Blackpool. Nina Hodgson was the wife of an old Army friend from my National Service days in Egypt. I had stayed with them when interviewing in the Blackpool area and she had seemed interested in what I was doing. Before approaching Nina I discussed the problem with my wife. Mary made a completely unexpected suggestion. ‘Why don’t you have a go at writing it yourself?’

And that is what I did.

The Literary Agent

I had long since set up an ‘Ops Room’ in the poultry farm offices. On one wall I had pinned up the six Corps maps from the Official History showing the whole attack front of the Somme first day. Another map showed where I was carrying out my interviewing trips in Britain. Business visitors had been following the progress of my work for more than a year. It was at this time that one of them asked me, ‘Have you got a literary agent yet?’ I had never heard of such a person. It turned out that a close friend was one of the leading agents in London and he gave me an introduction. He was Michael Horniman of A. P. Watt and Son. In an initial telephone call it was arranged that I would send him an outline of the book. I still have his reply:

I am getting an opinion from an expert on the prospects for your book but I am afraid that they are not likely to be good. Presumably you know of Farrar-Hockley’s, Brian Gardiner’s, and John Harris’s books on the Somme Battle and it is doubtful whether there could be much of a market for a further book even if it incorporates new material as yours would.

However, I will write to you again as soon as I hear what the expert has to say after seeing your synopsis.

On my next Egg Marketing Board visit to London I went to see Mr Horniman. He received me kindly. I cannot remember whether the expert’s reply was in yet; I have no record of that. But I naively asked him if he would represent me. I was taken aback by his reply: ‘Mr Middlebrook, I make my living out of handling saleable material. You have not yet convinced me that you have this. Write me five chapters and I will let you know.’

This was the first of two opinions from the established literary world that might have led me to give up. After all, I had achieved the interesting experience of the research and interviewing that had been my original ambition, and had carried out another interesting visit to the Somme to gather further information. But was I to settle for those results and not try to go for the book that John Howlett, Patrick Mahoney and many others hoped they were going to see one day?

I decided to accept the challenge – but not five chapters; I would write half of the eighteen planned chapters.

The First Nine Chapters

No one ever advised me on how to write; I just developed my own methods. I made no attempt to develope a distinctive style, just told the story in as simple a manner as possible. I was sure that the original material Patrick Mahoney and I had obtained from the Public Record Office and the personal accounts from the old soldiers would be sufficient merit for the book to be accepted by a publisher. I often felt that I was ‘constructing’ a book rather than writing one.

That did not mean that my spelling and punctuation were anywhere near acceptable twenty years after leaving school. I can tell two good stories against myself from my early writing days. The very first piece that I wrote, in my farm office, were some paragraphs describing the aims of the book. In my ignorance I did not realise that this, written by the author, should have been called the Introduction and that the Foreword to a book is a testimonial written by an outsider. I thought the latter term was the correct one. I took it through to Sonia, my business secretary, and she typed up what I had written. I took it home at lunchtime and proudly showed my wife the first actual writing I had produced after a long year and a half of preparation. Her response? ‘You can’t spell Foreword, can you?’ I had spelt it ‘Forward’. Am I the first author to have spelt the first word of a first book incorrectly? I crossed the word out in disgust and substituted ‘Introduction’.

The second story was the result of my distributing the first typed drafts of the chapters to six friends – John Howlett and his wife Margaret were two of them – who had consented to read them. Their comments were always useful. It was at the end of the third chapter, I think, that Anne Clarkson, schoolteacher wife of my Poultry Manager, wrote: ‘Have you never heard of semi-colons?’ It was sometimes hard for this businessman to relearn the basics of written English.

How to bring in the Men

I found out later that a publisher is not too concerned about an author’s failure to spell every word correctly or to understand every point of grammar and punctuation. Experts employed as copy editors can easily correct those mistakes. What a publisher wants is someone who can write a sound, interesting, original story. As I worked through the early chapters, I felt that the research and personal material, and my understanding of the structure of the Army, almost caused the book to be writing itself – except for two aspects that I gradually felt were becoming the cause of difficulty. Both concerned the manner in which the experiences of the individual soldiers should be treated.

At each morning’s writing, I had before me the first-hand accounts from interviews or correspondence with the Somme men. Initially, I turned these into third-person prose, using them as examples of events of the battle. But I remember clearly one morning looking at what I had just written in this way and thinking, ‘Why am I turning such superb accounts into general writing and coming between the soldier and the reader? Why not let him speak directly to the reader?’ And that is what I did.

The results are to be seen all through the book. The original words were reproduced in the first person, with the man’s name and unit in brackets at the end of the passage. I also decided that, to keep alive the spirit of the ‘Pals’ type of battalion going into action for the first time, such units would be identified by the original titles adopted by them when they were raised, rather than the Army’s titles given when they were taken over by county regiments several months later. In this way, the 15th West Yorks were described as ‘The Leeds Pals’ and the 20th Northumberland Fusiliers as the ‘1st Tyneside Scottish’ etc.

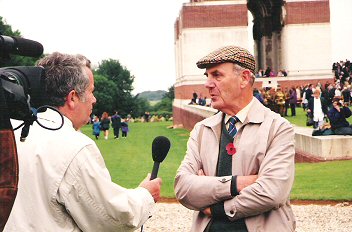

The use of the direct quotations worked very well and I used the same method in every book I subsequently wrote that contained personal material, although I later came to believe that putting the contributor’s name at the end of the passage was not the best way of naming that person (I had lady contributors in later books) and that introducing the name and unit before the quotation was better. Looking through my later books, I see that it was nearly ten years later, in The Battle of Hamburg, that I started to make the change. (The photograph here shows me working in Hamburg.)

Another mistake I made was to use abbreviations for ranks, thinking that a publisher would like the author to save as much space and, thus, cost as possible. It was only later that I realised that a good publisher does not worry about the cost of the handful of extra pages required to produce as ‘clean’ a manuscript as possible. I see that I ceased using abbreviations for ranks in my second book, The Nuremberg Raid.

The second difficulty I identified was that, while the first-hand accounts of my contributors described the battle so vividly, they were describing the battle though the eyes of the survivors and did not sufficiently convey to the reader the sense of tragedy in the loss of individual life. I decided to introduce a group of individuals who would enter the story, not through quotations, but in normal prose form. The reader was supposed to become identified with them as individuals who would suffer a variety of experiences, including that of sudden death. Instead of the reader just being told that so many thousand men in a division or hundred in a battalion were killed or wounded, I wanted the reader to be suddenly saddened that men such as a Nottinghamshire miner with a large family, a Belfast apprentice and an over-age stockbroker from Surrey could suddenly have their lives snuffed out.

I stopped writing and carried out a great deal of new work identifying a group of such men and obtaining further information on them to give them the necessary depth of character. Several men were visited again. I tried to assemble a group who would mathematically represent the units, ranks and experiences of the men who took part in the battle. I originally had fourteen men in the group, one for each main division in the front line on July the First, but I cut them down to twelve because I did not think the reader could carry fourteen in their mind through the chapters. I later reduced them down to ten for the same reason. The two cut out at that stage were Private Harry Bloor of the Acrington Pals and Private Tom Easton of the Tyneside Scottish. The long car journeys made to Lancashire and Northumberland for their extra material were not entirely wasted; several good new quotations were obtained and enriched the regular parts of the book.

But Reginald Bastard, Percy Chappell, Philip Howe, ‘Paddy’ Kennedy, Dick King, Billy McFadzean, Albert McMillan, Charles Matthews, Bill Soar and Henry Webber were all introduced – two to be killed, one wounded and one taken prisoner on the day; one more to be killed, one more wounded and two more taken prisoner later, leaving only Percy Chappell and ‘Paddy’ Kennedy from my representatives of ‘The Army of 1916’ still at the front at the end of the war.

It was an unorthodox and, possibly risky, method but it seems to have worked. No one has ever criticised me for it, but I never used that device again.

The Literary Agent Again

I finished the first nine chapters and took them to London, with a synopsis of the remaining chapters, and left them with Michael Hornimam. This was what he wrote to me a few days later:

On the credit side, I can report that I read your first nine chapters of THE FIRST DAY ON THE SOMME with much interest. On the other hand I must confess that I still feel some of the doubts which I first expressed to you. Specifically, I am not sure what market there is for this book.

However, there are four publishers in particular whom I think may be interested and whom I propose to approach. I am sending your typescript to the first one today, having ascertained on the telephone that he would indeed like to consider it.

Well, at least he had accepted me as one of his authors! There was a temporary shock when he told me that the publisher concerned was Penguins. I had hoped for a hardback publication, not paperback, but he soon explained that it was the Penguin Group, one of the foremost in the publishing business, and that, if a publication was to come, it would be by their hardback imprint, Allen Lane, the founder of Penguins.

The Publisher

Michael – we were soon on Christian name terms – told me that he expected Penguin’s answer in about a month. I actually had to wait for thirteen weeks. I became very anxious. I was eventually asked to go to Penguin’s offices in London to meet a Mr James Price. Patrick Mahoney, who had almost adopted the book as partly his own, came with me and waited outside while my meeting took place. Mr Price explained why there had been a delay. The chapters and synopsis had been sent to one of his regular military historian authors for an opinion and he had been waiting for the result. James – the Christian name terms came later here as well – had copied the long reply, cut off the address at the top and the signature at the bottom, and he gave me the copy to read. I have it in front of me as I type this story.

The advice was not encouraging:

‘Is there a market for another book on the Somme unless it has important new historical material or something new in the way of a viewpoint to offer?’

‘I don’t doubt the chaps Middlebrook has hunted up are unique to him, and therefore fresh, but what they say is pretty familiar stuff, from Sassoon and Williamson onwards.’

‘He tends to repeat all the old bromides about the high command and the cavalry….’

‘His account of the army’s organisation and of the trench system, and the situation in France generally, is really like a child’s guide’.

And so on:

‘flat and boring in the narrative’, ‘owlish self confidence’, ‘not exciting enough to attract or hold the general reader’, ‘I am left with a sense of mistrust, both of knowledge and judgement’.

I concede that parts of the criticism were justified; I was inexperienced at that time and the book would need a lot of work doing on it before it was fit for publication. But here was an established historian judging my work by the standards of his own approach to history. He referred to ‘a book on the Somme’, without realising that I was writing only about that dramatic first day, surely worthy of a book on its own. He quoted the works of such as Sassoon and Williamson that he saw as having satisfactorily covered the subject of the personal experiences of the wartime men. But Sassoon and Williamson were both officers and most other memoirs were by officers. Could my critic not see that there was a mass of ‘other ranks’ who had to implement the plans and suffer the consequences of the generals that he and his fellow historians spent their working lives studying? Could he not see that I was trying to write a new sort of book for a new sort of reader?

But James Price had recognised those points. I was to be given a contract and Penguins would publish the book. There were conditions. I had not up to that point invested the time and money to cover the Ulstermen of the 36th Division who had done so well at Thiepval, or any of the men from the German regiments facing the attack on the July the First frontage. I was to remedy this. Also, he wanted me to expand the existing British first-hand material; could I find another hundred men who had been in the battle?

I agreed to all of these reasonable and sensible requests. I went and told Patrick; we went and had a modest drink.

I still have the contract negotiated by Michael Horniman, dated 30th of December 1969, just over two years since the visit with John Howlett to the Somme and eighteen months after finishing John Harris’s Covenant with Death and my declaration that I was going to write a book. I was to receive an advance of £750, but not until the book was published. In fact, Michael Horniman arranged interim payments to be made when it became obvious that I was fulfilling my part of the agreement. I also have a note that my expenses amounted to £1,833.24p by the time the book was published.

It was a standard contract. The advance would be deducted from future royalties. The royalty rate would be 10 per cent of the hardback retail price, rising to 12 ½ per cent after 4,000 copies were sold (that sales figure was never reached). A paperback deal might be arranged after two years at 7 ½ per cent royalty, rising to 10 per cent after 30,000 copies (it took twenty-five years to reach that figure). If I were to write another book (I had no plans to do so) Penguins were to have first option.

I have much to thank both Michael Horniman and James Price for. The first publisher who had seen my raw, incomplete typescript had accepted me, a complete novice author. I have always said that James Price’s decision to pay for an expert opinion and then back his own judgement represented the best tradition in publishing. Both men had also made good commercial judgments; Penguins are still making profits from the book more than thirty years later and Michael Horniman’s successors still collecting their 10 per cent commission.

Who was the ‘expert’? I believed that it was Correlli Barnett who had a book, Britain And Her Army being prepared for publication by Penguins at that time. I hold no grudge against him for his views. Much of his criticism was valid and I reacted by working hard to prove him wrong.

(After writing the above, I decided to contact Correlli Barnett, sending him a draft of the relevant passages and giving him the opportunity to comment. I received a prompt reply. He confirmed that he was the writer of that opinion more than thirty years ago. He also gave a robust reaffirmation of his views then and stated that he still held them as firmly now. He had no objection to my including them in this web article.)

Back to Work

I went to Northern Ireland and interviewed the Ulstermen. I remember being shocked at rows of recently burned out terrace houses in Belfast and being advised to remove the GB sticker on my car when I stayed overnight in Cookstown, Co. Tyrone. I also travelled right out to Clifden on the Connemara coast in the Republic to visit Lieutenant-Colonel Irwin of the 8th East Surreys to obtain fuller details of the Captain Nevill football story.

I advertised in German newspapers where the Regiments facing the British on July the First had originated. Because the Germans had been outnumbered seven-to-one that day and I was not expecting anything from East Germany, the response was modest. To get the best from the small number of replies, I decided that I should visit them all. But I did not speak German at that time. Most of the replies were from the American military zone so I approached their Military Attaché in London and asked if a German-speaking officer could be detached for what I thought would be an interesting few days for him or her. I said that I would pay all expenses. The reply, in what I detected as a southern U.S. accent, ‘Sir, we do not hire out our soldiers’.

I then approached the Ministry of Defence in London and asked for an interview with the Army’s Director of Public Relations, hoping that an officer from BAOR could be provided for the trip. Who turned out to be the Director? Brigadier Anthony Farrar-Hockley! He could not have been more helpful. He did not follow the BAOR route but put me in touch with a post-graduate Oxford German linguist who ‘for a Fiver and his expenses’ would gladly carry out the task. His name was Tom Steele. I must pay credit to Anthony Farrar-Hockley for his generosity of spirit in helping a project that might have seemed to be a rival to his own book on the Somme.

Patrick Mahoney had been promised a tour of the Somme as reward for all his earlier research efforts. A combined tour was arranged – Germany and the Somme – and off the three of us went with me driving. It went perfectly, despite some tricky navigation problems in Karlsruhe and a rude, deliberately unhelpful, photo archivist at Munich. The German ex-soldiers cooperated fully; they were amazed that someone had come from England to talk to humble soldiers from the Somme of more than half a century earlier. Tom Steele’s interpreting was excellent. We returned via the Somme and Patrick got his promised tour of the battlefield. He has rung the AA before leaving England, asking what was the best restaurant in the Somme area so that he could treat Tom and myself to dinner there. And so we dined at the famous Godbert’s in Amiens and were hospitably looked after by the lady owner; she invited us to add our names to her Visitors Book. We were fortunate; the restaurant closed a few years later.

(Tom Steele’s name was thus added to the growing list of people who were helping my book forward. We remained in touch. When his first child, Harriet, was born, Tom and his wife Margaret asked me to be godfather. I recently took the now charming young lady to lunch in Soho, and the family even more recently gave me hospitality at their home in Wimbledon when my wife had a serious operation in London.)

The final part of the bargain with Penguin’s James Price was to find another hundred British contributors. I did that. The eventual tally of participants from July the First was 535 British, Ulster and Newfoundland and 20 Germans.

I finished writing the book, a task that involved much insertion of new material and some revision. I drew the maps. My brother-in-law, Ted Sylvester, redrew them to architectural accuracy. Penguins provided a professional cartographer, Leo Vernon, who brought them up to professional publishing standard. Once again, I found myself working with someone who could not have been more helpful. The maps went backwards and forwards for increasingly minor changes. Some of the consultations took place in the Waiting Room at Hitchin Station. I broke my Egg Board journeys to London there; Leo lived there. Photographs were assembled and captions written. But work was far from finished.

I should explain that the manuscript of a book normally goes through two editing processes. (It is actually a ‘typescript’ following the invention of the typewriter, but publishers usually use the older term.) A ‘commissioning editor’ goes though the manuscript and advises on the content. He can insist upon alterations because the contract says that the publishers will definitely publish the book ‘provided the manuscript is delivered to their satisfaction’. Enter David Thompson, the commissioning editor appointed to this task. I pass quickly over the gruelling process where he coerced me into corrections, clarifications, expansions or reductions to the manuscript. These consultations usually took place in the Members Room at the Egg Marketing Board’s offices at Shaftesbury Avenue on days when no Board meetings were taking place. I remember the last confrontation when the points at issue had dwindled to six in number. After a process of give and take, those final points were settled. I later found out that it was David Thompson who had seen my initial first chapters and synopsis and recommended the book’s potential to James Price. I never met David again but the book may never have been published without his initial faith in it and would not have been so good without his editing.

After the necessary delay for typesetting, the galley proofs arrived with instructions to check carefully and return within a certain number of days. It was then that I saw what the copy editor had done to my typescript. I was horrified at the way he had instructed my abbreviations in capital letters to be set. I learned then the terms ‘upper case’ and ‘lower case’. He (or she; I never met him/her) had used lower case for most of the capitals. Look in the book and see how ridiculous the plurals of such abbreviations as N.C.O., H.Q., and C.C.S. look in the copy editor's lower case form.

If I had been more experienced I would have insisted on changes but I felt – probably unjustly - that Penguins were becoming concerned at the long progress of and cost of the pre-publication process. It was a mistake I never repeated; I learned to stand my ground with copy editors in later years. For the centenary "First Day" editions published in 2016, both Penguin, in the paperback edition, and Pen & Sword in the harback edition for which they now own the rights, agreed to correct the worst treatment of the typography in the first edition of 1971, at some large amount of time spent by their production teams, and with great satisfaction to me and, I hope, easier reading for new purchasers of both editions.

Mary, my ever-helpful wife, helped with the vital task of proof reading. Then the publishers asked if I would like to do the index or have it done by a professional for which I would have to pay. I decided to do it myself. Someone had told me that one indication of the merit of a book is the depth of detail in the index. Instead of just a long list of page numbers after a prominent entry, there should be sub-divisions. I decided to give the index the full treatment; I notice that ‘Haig, Gen. Sir Douglas’ has fifteen sub-divisions. So, another two or three weeks followed with a table full of index cards and scattered notes. Mary, together with my daughters Jane, Anne and Catherine, were valued helpers at this boring task.

Eventually all was finished, packed up and taken to London to be handed over to Penguins.

Publication

|

The book was published on July the First, 1971. It was three years and three months since I had declared my intention to write a book. There was no launching party in London, only a modest family lunch celebration in Boston. Penguin’s Publicity Department worked hard with some success. There were a few national reviews, mainly in specialist magazines rather than the press, although Roy Hattersley published a favourable review in The Guardian. Anthony Farrar-Hockley was also complimentary, although he wrote that he would have preferred to see the formal Army titles of battalions rather than the ‘Pals’ type titles I had used. John Keegan wrote me a complimentary letter. By contrast, John Terraine would make several critical comments in print in the following years, and the few occasions on which we met were never warm ones. |

|

The book received a warm reception in the Northern cities from which the Pals-type battalions came. There were good reviews in their local papers and a small round of local television and radio interviews. Considering that it was my first book and that I had no real literary pretensions, I was well satisfied and very pleased to see the book in that well produced Allen Lane hardback imprint. Penguins very generously gave a stock of free copies for distribution to my contributors. I inscribed each one to the man’s participation in the battle, mentioning his unit, and I know from subsequent contacts that they became family heirlooms. The published price of that hardback in 1971 was £3.95; the second-hand value of a copy of that first edition can now be in excess of £30. One aspect of the book that does distress me is that I was told that the market value of medals for men killed on July the First, 1916, became higher than those who died on other days of the war.

The Aftermath (if you look in any of my books, you will see that I usually have an Aftermath chapter.)

It was soon after publication day that Michal Horniman almost casually informed me that he had sold the American rights to W. W. Norton & Co, a New York publisher. I was amazed; I had never envisaged that there was such a thing could happen. All Nortons wanted was a shortening of the opening chapters – a simple task.

I had intended to return full time to my poultry business after The First Day on the Somme but that news from America led me to write two more books. I had satisfied my curiosity about a great battle on land in the First World War. I would turn to the Second World War and write books on the air and sea war. In this way The Nuremberg Raid and Convoy were published in 1973 and 1976. Not only did Morrows of New York take both books but a Berlin publisher, Ullstein, took them as well. I realised that I had become established. I was enjoying the work. I left my poultry business in the hands of managers and continued writing.

Two

Martins at Thiepval, 1st July, 1996

There was a further development. Around 1980 a small group of friends in Boston asked me to take them to the Somme. They paid me £5 and my expenses, just as I had paid Tom Steele to come with me as interpreter to Germany ten years earlier. A small commercial tour operator then paid me £25 a day to be the guide on two of his tours to the Somme. I decided that I could supplement my income and take up an interesting new career by setting up my own small touring organisation. My first tour took place in May 1984 with fourteen customers. I had no idea how long there would be a market for this activity; if I had been forced to put an estimate I would have said about five years. I retired from touring in September 2004, aged 72, after carrying out about a hundred tours to various destinations from the Somme to Gallipoli!

The accidental, almost casual, way in which I fell into writing military books and then battlefield touring turned out to be a boon. The introduction of the Common Agricultural Policy sharply raised the price at which my business was buying wheat for milling into poultry food. My business failed. It was my ‘books and battlefields’ career that kept me financially solvent for the remainder of my working life.

The First Day on the Somme’s Career

I still have all my sales records. The book sold 41,545 copies during the first five years. It seems an impressive figure but more than 80 per cent of the sales were to Book Clubs. The American Military Book Club took a huge 30,000 copies! (Book Club deals are a mixed blessing, beloved of publishers who can extend their print run and thus reduce the unit price, but not popular with this writer who objects to seeing his hardback copies sold at a cut price and earning only a tiny royalty - only 7 pence per copy after agent’s commission in that five-year period, compared with about 35 pence for the same book for a regular bookshop sale.) Penguins own hardback sales numbered 4,800 during that period and Morrow’s U.S. edition 3,075. I note that, to help keep the book in print, I bought a hundred copies from Penguins in 1975 for my private sales without taking a royalty. Penguins held the paperback rights and had said that they might consider publication ‘a few years after the hardback publication’, but nothing happened in those five years.

The second five years brought mixed results. Total sales were just under 20,000 copies. The Penguin hardback only sold about 400 copies a year. British Book Clubs took just over 5,000 copies but many of these were being sold as £1 a copy as loss leaders. Sales by the Americans had ceased completely. Penguin declined to publish a paperback but Michael Horniman arranged for Fontana to take the paperback rights. They printed 12,000 copies and sold them – at £1.50 each – but they did not reprint and their rights lapsed. Sales figures for each of my next three titles - all Second World War books – had already overtaken those for The First Day on the Somme.

Things went very quiet for the next twenty years and I thought at first that the life of my first book was approaching the end. British hardback sales numbered 2,633 and I see that again I kept the print run going by buying 600 of these myself. In the last six years of the hardback run, regular sales were only about 50 copies a year and Book Clubs took 2,250 copies, but the hardback print run finally expired in 1993. Penguins did, however, at last exercise their paperback option in 1984, thirteen years after the hardback publication! There was now a growing interest in the Western Front. Schools were covering the First World War; family history was a growing hobby; a ‘Western Front Association’ of enthusiasts had been formed in 1980. That Penguin paperback has been in print ever since, selling a steady 2-3,000 copies a year.

Then something extraordinary happened. Twenty years after its formation, the Western Front Association’s website conducted a survey, asking visitors to the site to name their five favourite First World War books in order of preference. More than 60 people responded. (I took no part; I was not ‘into’ computers at that time.) In an attempt to find what was described as the “Real Top Five”, the preferences were then added up, with five points being allocated to a first choice, four to a second etc. The results were posted on the website on December 26th, 2001. It turned out to be a great Christmas present for me.

I was delighted to find that The First Day on the Somme topped the list, but I was amazed at the extent of the lead. I had 99 points; the next four choices scored 39, 36, 27 and 26. (They were Her Privates We by Frederick Manning, Memoirs of an Infantry Officer by Siegfried Sassoon, They Called it Passchendaele by Lyn Macdonald and Goodbye to all That by Robert Graves.) The entire list contained 124 titles. Of those who had not approved of my book initially, John Terraine’s six entries scored 17 points in total; Correlli Barnett’s single entry – The Swordbearers, published nearly ten years before The First Day on the Somme - received one point. But Correlli Barnett, in his recent letter, says that "The popularity of a book is no measure of its worth as history". He may be right.

|

I sent a copy of the results to Penguins, pointing out that a generation of readers had not had the opportunity to buy a new hardback of The First Day on the Somme, and asking them to republish the title in hardback. They declined and the hardback rights reverted to me. I then sent the survey to Pen and Sword Books, a specialist military publishing firm whose offices are in an old Territorial Army Drill Hall at Barnsley – great people to deal with – and they did agree. In this way, thanks to the ‘voters’ on the Western Front Association website, The First Day on the Somme was reborn in hardback, thirty-one years after the original Allen Lane imprint. I have also just signed a modest contract with a Dutch publisher, Uitgeverij Aspekt of Soesterberg, for a translation and publication of The First Day on the Somme, thirty two years after Morrows of New York published the only other overseas version! |

Total sales of The First Day on the Somme so far are 129,599. Only one of my other titles, The Nuremberg Raid, my long-term bestseller, now exceeds this figure and it is likely to be overtaken soon. I am very much in debt to those men present ‘on the Somme’ on that ‘first day’ who contributed to my book, and to my family and many good friends from John Howlett and Patrick Mahoney onwards who supported and helped me – and, perhaps most of all, to my readers.

Martin Middlebrook, Boston, England, December 2004.

Footnote 1:

The

First Day on the Somme

did overtake The

Nuremberg Raid in

2008 and has now sold (as of November, 2017) over137,000 copies according to the most recent

royalties return.

Footnote 2:

January,

2017 - Sadly, I have to report the death in 2014 of my wife, Mary, who

helped me in so many ways over so many years, and more recently

of John Howlett and Patrick Mahoney, the two stalwarts from the

early years.

Martin

Middlebrook, Boston, England, May 2015, November, 2016, January, 2017, November 2017.

After The First Day on the Somme, Martin Middlebrook wrote The Nuremberg Raid, Convoy, The Sinking of the Prince of Wales and the Repulse (with Patrick Mahoney), The Kaiser’s Battle, The Battle of Hamburg, The Peenemünde Raid, The Schweinfurt-Regensburg Mission, The Bomber Command War Diaries (with the late Chris Everitt), Operation Corporate – The Falklands War, The Berlin Raids, The Argentine Fight for the Falklands, The Somme Battlefields (with Mary Middlebrook), Arnhem 1944, Your Country Needs You, Captain Staniland’s Journey, A Sergeant-Major's Death.

![]()

Copyright © Martin Middlebrook, November, 2004.

Copyright © Martin Middlebrook, November, 2004.

Return to the Hellfire Corner Contents Section