![]() THOMAS HUTCHINSON

THOMAS HUTCHINSON

![]()

Biographical Notes

Thomas Franklin Townsend (T.F.T.) was born on 26 January 1889, the son of Thomas Birch Townsend and Jane Ann Ewart of Coventry England. The family immigrated to Canada in 1863 and farmed a piece of land 2 miles west of the village of Harrowsmith which is located 10 miles north west of Kingston, Ontario.

After obtaining a Bachelor of Arts degree at Queens University, Kingston he spent the winter of 1914-15 in Regina, Saskatchewan as a student teacher. In 1915 he enrolled at the Wesleyan Theological Collage, McGill University in Montreal.

By 1916 the slaughter in Europe had been in progress for two years. As the number of dead in Flanders increased so did the army's requirements for new recruits. To a generation just emerging from the Victorian era, a distant war still conjured images of glory and adventure. The general public in Canada had not yet grasped the reality and the horror of trench warfare.

In the month of February 1916 T.F.T. made three monumental personal decisions. Firstly he decided to postpone his university studies at McGill and then on the 9th he married Lucy Ellen (Nellie) Medcof, daughter of the Rev. John Dowker Medcof and Eliza Jane Rowe of Hartington, Ontario. Thirdly, on the 14th he enlisted, in Montreal, for active service and became 530625, Private T.F. Townsend.

As a deeply religious individual he had strong moral reservations about taking human life. He wished to 'do his bit' yet not at the expense of his personal convictions. His solution was to select service with the medical corps which would allow him to work toward preserving life rather than taking it. For the duration of the war he served with the 9th Canadian Field Ambulance, attached to the 9th Infantry Brigade, 3rd Canadian Division and later at the 7th Canadian Field Hospital in Etaples, France.

Some take easily to army life but as his diary indicates, T.F.T. was not one of these. At this point in its evolution, the Canadian Army still retained many of the British military traditions. One of the more onerous aspects was the maintenance of the rigid class structure which separated the world of the officer from that of the enlisted men. T.F.T. appears to have mentally placed himself in neither the officer nor the other ranks category. He chaffed at this aspect of military life and the controls in general which were placed upon him.

Thanks to his literary inclination many incidents which he experienced in Belgium and France come to life in his diary. His constant conflict with the military censors, witnessing the deaths of gas casualties and the description of 'bath parade' are only some of the moments about which he vividly writes.

T.F.T. survived the slaughter in Europe. He remained with the Canadian Army in France and England until 1919 and, while awaiting his discharge, completed a semester at Edinburgh University. He completed his Bachelor of Divinity degree at McGill University in 1920 and was ordained as a Methodist minister that same year. His only child, Alma Jane Pauline, my mother, was also born in 1920.

He served as a minister with the United Church of Canada throughout southern Ontario for 46 years. For at least three decades following the war he maintained his connection to his military past by active involvement within the Royal Canadian Legion, serving several terms as branch president.

On the 8th February 1967 T.F.T. died suddenly and peacefully in his sleep. He was 78 years of age and one day short of celebrating his 51 wedding anniversary. He is buried in the civic cemetery in Belleville, Ontario.

Today eleven people claim direct descendancy to this one Canadian soldier who returned from Europe in 1919. 59,544 other Canadians did not. If one were to roughly extrapolate just the Canadian numbers into the present, the total cost to this nation would be approximately half a million potential souls. It is estimated that the total number of civilian and military deaths, directly related to the war was approximately 20 million. It defies the imagination to comprehend the total human potential which was forever lost.

This transcription is dedicated to the memory of my grandfather, Thomas F. Townsend, and to all the men and women of that decimated generation.

Thomas F. Hutchinson,

Edmonton, Alberta.

Canada.

2003.

Editorial Notes

The diary is a hardcovered and cloth bound notebook measuring 7' x 4 1/2' and would fit easily into the pocket of an army tunic. Due to his often-stated uncertainty regarding the expected length of the war he adopted a very small script in order to maximise the available pages. The diary pages are lined and he used two lines of writing for each ruled space.

Throughout the period during which entries were made several types of fountain pens and lead pencils (often dull) were used. As a result of the tight script and blurred letters it was sometimes difficult to interpret the text. If a word could not be deciphered it is indicated by __?__. With few exceptions he did not bother with paragraphs, again, because of his concern about conserving space. I have added the paragraph structure in order to make it a little less dense and easier to read.

I have added the [Italic text in square brackets] in an attempt to enhance or clarify.

The text which appears (bold in round brackets) at the end of some of the daily entries are notations made in the Unit War Diary by the Commanding Officer. I have included them in order to show what was deemed relevant by those at the opposite end of the command structure.

T.F.H.

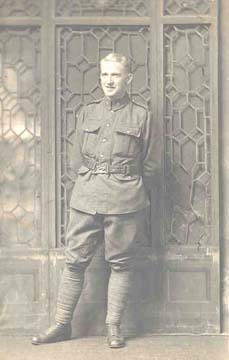

Thomas Franklin Townsend 9th Canadian Field Ambulance Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1917 |

|

March 24, 1916. London

Under the guidance of an old printer, Waterman1 and I visited Trafalgar Square, Buckingham Palace, Westminster Abby, The Old Curiosity Shop made famous by Dickens, St. Paul's Cathedral, the monument erected to commemorate the Black Death, the Fish Market noted for its good fish and bad language, London Tower, Tower Bridge and returned by London Bridge. In the evening three of us visited the Wax Works [Madame Tussauds]. A day could scarcely be more full. I think we saw as much this day as anyone could see in a day, of wealth, grandeur, tombs of kings, their prisons, their weapons, their instruments of torture and oppression.

I know of nothing which could be more impressive than the Service of Intercession in the Abby, there, among the tombs of the mighty, great folk of a thousand years, England's rulers, poets, warriors, statesmen and queens. What a nation. Greatest in age, in grandeur, in world wide labour for the betterment of the race.

1 530691 Albert Jabez Waterman of Newfoundland

The most effective method among the many, to preserve the memory of one dying, was that of a certain duchess. Every Saturday, out of the estate of her heirs, a certain number of poor widows are given a loaf of bread and a penny in her memory.

We saw the Bloody Tower, the place where Raleigh spread his cloak in the mud for the Queen to pass over. The balcony where Lady Jane Gray stood to see the execution of her husband, the path along which she walked a few moments later to her own death. Walking up the winding stone stairs and through the old prison I saw walls which are marked with their names which they cut in stone to wile away the weary hours. One could feel how these wretched mighty folk suffered.

These things are too big for me to write about. Many of the tombs are covered with sand bags to prevent destruction from bombs. The oldest windows were being taken out. Many evening church services were cut out especially St. Paul's. Busses passing this cathedral and going over the bridge must extinguish their lights. Powerful search lights and anti aircraft guns are mounted in a high place here and there. The traffic is cut in two.

March 26, 1916

Hunting up a famous preacher I finally heard Dr. Horters at Westminster Chapel. Visited Hyde Park, a large stretch of grass with seats for thousands. The grass grows so well no fear of people destroying it getting to seats. Returned home for service at Haslemore and into camp and mud before nine.

We saw many soldiers returning from the Front, on leave or wounded. One said fighting was not a bad job if it wasn't for the dirt. He hadn't had a wash for over a week. One fellow was a graduate of McGill. He was returning home from graduation ceremonies when he enlisted. Had been wounded and sent back. He was on a machine gun. In a charge one day the Canadians had passed him. His gun no longer of use he grabbed up a rifle and went along receiving a slight wound. When he had lain for some time he saw a German coming at him with a rifle and bayonet. He got up with what strength he could muster but could not fire before the bayonet had gone into his side. He struck his foe down with his rifle butt and killed him with his bayonet. He had enough of war.

Many of the returning men were ragged, haggard looking, with wiry muscles and thin cheeks, but a great spirit shinning through their eyes. War is a game which fills them with horror yet many of them love its wild excitement and desire to go back.

March 27, 1916

Ice on the puddles and a few flakes of snow. I am a mess orderly today washing stacks of dishes and greasy pans.

March 28, 1916

We marched today out to Hindshed Heath for a review by Sir Sam Hughes returning at 2 P.M. famished, find mail from home. A wild night with heavy snow, wind and rain. I find a cozy room at the Soldiers Rest and write. We may leave any day now for France.

Tucker2, McIntyre3, White4 and I are on sentry squad. We receive a lesson in sterilizing water. A very good thing they say.

2 530626, Herbert Tucker, of Kingston Station, King's Co., Nova Scotia, remained a close personal friend throughout the war. He survived the conflict and became a United Church Minister.3 530578, Andrew Thomson McIntyre, of Norden Largs, Ayr, Scotland.

4 530682, Edwin White, of Montreal.

(General Review of Canadian Troops on Ludshott Common by Minister Militia Major General Sir Sam Hughes. In the afternoon all Officers met the Minister at a reception. – Commanding Officer, Unit War Diary)

March 29, 1916

Ground frozen hard and the boys joke about English weather and the Englishmen try to explain. We received identification disks on morning parade.

This afternoon I had my first experience at stretcher drill, charging down a hill after supposed wounded men. Rather hard on soft muscles. When we returned the fellows played a continuous joke as the late comers returned. ‘There was mail down in hut 22’. With hasty steps they ran down. They returned with ruffled feathers while fellows cheered. It was a mean trick.

March 31, 1916

First real duties on sentry squad. We are rich now. 10 bob came our way. Harrah for a current bun and a cup of tea in the morning.

April 1, 1916

Stretcher drill again. A march of about nine miles through lanes and byways to a commons covered with bush and broom, trenches and sunken roads. Some of us play dead and wounded while others rush to their assistance, and a fine jolting we poor wounded got. From 9:30 to 11:45 General Jones inspects us and tells us we will go to the Front any day now. It's the real thing for there will likely

be a repetition of Ypres of last year5. We shall be needed in dangerous and difficult work. More squad drill and hard days work. A fight in the kitchen since C.A.S.C. [Royal Canadian Army Service Corp.] have been making free with our rations.

5 This is a reference to the 2nd Battle of Ypres, April 1915 which was the first major battle the newly formed Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) took part. More than 6,000 Canadian casualties were sustained in this battle. It was noteworthy since it marked the first instance of the German use of poisonous gas.

Bert conducted service at night.

(Inspection by Surgeon General Jones, D.M.S., Canadians. – Commanding Officer, Unit War Diary)

The usual duties in the morning with medical inspection. Off by 2:30 and such a walk, some 8 miles through Greyshott, Hindshed, Haslemore, Hammer, Shottermill, Bramshott6 villages by way of the Devils Punch Bowl, the Murder Stone, Gibbets-Cross. Wild moor land mostly. Paths leading down under the shadows of ancient hedges, through bush and holly, beach, oak, passed gentleman estates, little old farm houses, mostly quaint with hedge and garden. One of the most enjoyable walks I have ever had. The ways are winding, crossed and inter-twining so that we have to enquire our way.

6 The Canadians were occupying a military camp near the village of Bramshott, located 20 miles NE of Portsmouth and 40 miles SE of London.

A supper at Soldiers Club, a little devotional service in Soldiers Rest, then home. Have a number of cards for Nellie that recall the beautiful scenery.

April 2, 1916

Usual sentry duties keep us from service. At 10:30 comes the orders no man out of lines today. We take it as a sure sign of departure. We are shooting Germans and are being shot by them in our dreams. We are not worrying any though. By diligent effort inspired by laziness I escape all special duties of packing and preparing after getting my own kit packed. I go to YMCA to write letters. Since we had but one blanket left from our beds Bert and I bunk on the floor together. There is a general chorous of coughing, snoring, restless movements to keep warm. Clouds of

smoke from a stove. Fitful dreams entertain me rather than sleep for the greater part. Reveille at 4:30 etc.

(The unit received orders to leave for Southampton. – Commanding Officer, Unit War Diary)

April 3, 1916

Started at 9:45a.m. with all kit aboard, part of Sec. B. Trudge for 3 miles under increasing weight and rising atmosphere. Who imagined the old hero Atlas with the world on his shoulders. Was he a British infantry soldier on a ten mile march? Train at Liphook. Good bye Bramshott and Hut 24. On to France and war. Can not realize it. More like a pleasure trip with a hazy got-to-go someplace in our mind. Yet we expect wounded men to carry, the thunder of guns, and all of red war before the end of the week. ‘Pack up your troubles in your old kit bag and smile, smile, smile’ is the current song. What great medicine smiles are for all manner of the diseases of life.

Port reached and we read letters received today and take sun baths. On board at 5 p.m. and out into the harbour to spend the night. Ships on all sides, thousands of soldiers. Some hospital ships with red crosses on side.

Clockwise from upper left. H. Tucker, G.E. Bee, B.J. Warr, T.F. Townsend. ‘Stretcher squad #1 after an engagement in Flanders, and after a ‘wash up’. Note on reverse. ‘These shrapnel helmets are fine things to protect ones head from shrapnel shell but will not stop a bullet excepting a spent one. They are rather heavy but one doesn’t seem to mind the weight under shell fire. Belgium, June 18th, 1916’

(Entrained at Liphook in two parties for Southampton (9A.M. and 11 A.M.). Arrived at Southampton late in afternoon and went on board T.S.S. Maiden. Supplies, medical and otherwise, taken on board. Horses placed on forward and aft deck. Officers were the guests of the Directors of the Company and provided with cabins and meals. Men lived below decks and used the iron ration. Left dock at 5:30 P.M. and anchored out in harbour. – Commanding Officer, Unit War Diary)

April 4, 1916

Still here. Aeroplanes often seen. We know not why we linger. A fight almost for our 24 hour rations and we take them over into a corner to eat. The day warm. We read and talk on deck until nine in the evening. Every star is out, lights from the city and shore, lights from the ships far and near, streams of lights searching for secrets the sky may hold. Bert and I bring our blankets on deck and sleep under the watching stars. Deck planks our bed springs, wooden life belts our pillow, our great coats our coverlets, our bedroom light the Great Bear and Polaris.

An argument with Bee7 and Warr8 on is it [the war] worth while. Warr is discontented and speaks rather unpatriotically at times, likely when the call of home is loudest. Is the thing to be gained worth the sacrifice? Is the brutal bloodshed and mutilation of the best and bravest worth it all? What of the broken hearts and the pinched lives of the tender ones who love, the life of toil, poverty and the lack of education in our children as well as the brutalising effect on those of us who return safe? What if the British Empire should fall and Germany goes down in the pages of history as the conqueror of the world. 'Tis not to keep treaties, to defend the weak nation or to assist friends we fight but for Britains life and supremacy. More truly the fight may be against a false and ruinous philosophy, a perverted idea of God and life as well as to maintain the high Christ ideal of greatness through humility and service against the brutal ‘red in tooth and claw’ ideal of the survival of the fittest. German ideals would never have a vital grip on the Anglo-Saxon mind or of the world in general. Revolution would have come gradually and bloodless as the greatest revolution which Britain in 18th and 19th centuries did.

1 530514, George Ewart Bee of Birmingham, Warwick, England.2 530631, Baxter James Warr of Montreal.

Germany a world conqueror - so was Alexander and Caesar and we now read with pity at the futility of it all. Should our descendants read of the fall of Britain and the rise of Germany? Britain can never fall. Her ideals of peace and patient industry, her consideration for the individual, small and great, would rise and revolutionize the world, not by power of sword, but of mind. Is not the truth that men love to handle huge instruments even if they be of huge destruction to make the world groan for decades of pain, to fight and risk and destroy this mighty and mysterious thing called life. Mighty question this, is it worth while, is it justifiable? Was there ever a war that paid in human advancement for the human destruction? Is it not all a mighty unbelief in the power of truth, faith and love? Christ has shown us that love can conquer all things and we half believe it in the case of the individual. If a man does you an injury, by self control, fellowship and assistance you conquer him by thus appealing to his higher nature. Can it not be true of nations and races? Cobden and Bright appealed to the humanity of landowners and conquered them. Welberforce overcame the greed of slave traders. So could the idea of justice and the necessity of individual freedom to human advancement put down German tyranny though it did for a time flourish world wide. Who is there that can stand up in the light of heaven and declare that God made the universe and saw that it was good, that he yet rules and leads men in life nearer and ever nearer to His life and at the same time utter such paradox that any evil is necessary to life. His God, as yoke fellow, co-partner, and assistant toiler, any Satan? Does Christ our Redeemer have as consort in the throne chair beside him any hideous fellow god named WAR?

I can't understand how fellows take life and death.

Here are two jokes. The OC [Officer in Command] has remarked that casualties would occur almost immediately. In comment M. Sill said, ‘Just think what new scenery will surround us next week’, referring to the next world. Another speaking about leaving his polishing materials home. ‘I shall not polish my buttons again until I am up on my way to meet St. Peter’.

April 5, 1916

Still here and we have all manner of wild guesses. If one wishes to hear terrible talk take up a position on a troop ship isolated by the ocean. It was a lazy day barren of events. The time not dragging much because of a book, a lady to dream of, many dangers ahead from which we are safe here. As we made our bed the ship lights were out and we sat in darkness with ears at attention for the whurr of a hostile aircraft. We creep among sitting and standing men and go up to the deck to see. It proved to be some fault of the machinery on the ship. Aircraft of various sizes are seen almost continuously in the morning. They sail along very beautifully with a huge noise. The Hindoo ship crew walk among us with ‘Hot tea John?’ and cakes wrapped in doubtful looking cloths looking for pennies. Their thin black bodies are slightly clothed. My bed is on the floor some one foot wide. Cold toes. Wishing for morning. The news? Battle in the channel, many submarines. Two troop ships sunk. Zeppelin raid on Scotland, etc. Bert and I practice communion with rations and it works since it is not met with difficulty on a stomach of unequal size.

April 6, 1916

Still her in some channel, gulf or river mouth of which my doubtful geography will not give a name. Some fellow suggested as the cause of delay - they have not room for us in Bramshott so they shoved us out into the ocean. Well there is room here. Many ships with soldiers pass but here we are - period. Lorna Doone is my pass time and I enjoy it greatly. My chief temptation is to write a letter to Nellie. This is the fourth day without a line. Hard biscuits today. Tomorrow we can say a heartier Grace over rations of bread. Buy a leathery flapjack [pancake or chapati] from a Hindoo for 3 shillings. Robbery but hot. Try to sleep on deck but a few drops of rain drive me down to a bed under a table - the jungle of men gamble in pennies and quarrelling at it. A talking machine [record player] is playing hymns, others are swearing as they make their beds at which an Anglican student holds up a hand and they cease for a minute. Another is reading his evening passage of scripture beside a bench. Rolling and tumbling, swearing as they retire, floor covered with an indiscriminate mess of sleeping men, kit bags and equipment, pails, brooms, rubbish, the dim lights from the side of the huge cattle steamer, the continuous thunder of the horses pawing on the resounding iron deck just above. In the middle of such confusion I lay down to sleep like a child whom his mother has kissed good-night and tucked in.

April 7, 1916

Still here. A day on guard in the hold of ship. Though against orders I wrote part of a letter. I was glad of the duty. A ship towed in, as if lame, nationality guessed at. A hydro plane went past, first in the air then in the water. The first I have seen of these wonders of the air and seas. We leave by 8 p.m. and by 9 p.m. we are in the channel. Lovely scenes of an island, an ancient stone castle standing like a forlorn ghost with dumb mouth lamenting of glorious days gone by. We pass Osborn House where Queen Victoria died, the town seen indirectly through mists, the water coloured with sunset. War boats whistle and bark, lines indicate submarine nets and mines. No chance for Germans here.

(Ship remained at anchor until evening of April 7th, then she left Southampton at 7:30 P.M. and was escorted across Channel by torpedo boat destroyers. The delay was due to submarine activity near Havre. - Commanding Officer, Unit War Diary.)

April 8, 1916

Le Havre - Second wedding anniversary - two months since. In Canada she will soon awake to it and wonder where I am. Last 9th on the Atlantic, this, my arrival in France, next in the hands of God.

Things look a little foreign, enough to remind me I am on a foreign shore for the first time. Soldiers with their curious light blue trousers, like bloomers. Lamentable waste of cloth in war time. A small group of German prisoners go by. The first I have seen. Dirty ragged clothing, tunics patched and worn. We all rushed like a bunch of school boys to see them but were turned back by our Sgt. Major. We sun ourselves on the dock and eat cake and sandwiches. We march up a long winding road to the highest hill and sleep under canvas in a beautiful spot. Just a little cold. Bought a post card for Nellie. Got a card after inquiring at a dozen places. Officers give instructions!

(Arrive at Le Harve at 2:30 A.M. April 8th. Men were disembarked and marched to Rest Camp #1, Sanvic, just outside of Le Harve. Inspected by Camp Commandant. – Commanding Officer, Unit War Diary.)

April 9, 1916

We could not go down town last night on account of unexpected and hasty orders. We are told we leave for the Front today. Men from Egypt shiver a bit as they wash. They had finished up war in the east and now must help us. France is very much like English scenery with mist, hedges, plants, houses more elaborate in decoration. Many English signs, many Belgian flags. A lovely place, the hill by the sea with ancient houses. Grand buildings used for hospitals by the English. English and Belgians seem to be as much in prominence as French except in the language of the people. Flower market with perfume, immense shipping, cotton piled high in places.

April 10, 1916

The calendar in my mind went wrong9. Instruction in stretcher drill, motor wagon [truck type ambulance], etc. We know now we shall be on stretcher bearing work. Take news without a change in feeling. A route march out through the city, out through fields and meadows, along the cliff, back through the Australian camp. The most miserable human creature I ever saw, an old woman rag picker at 75, red eyed, face besmeared, lonely. Captain held me up for long hair and therefore got off short. Wrote letter for censor, first time10.

9 The date of this entry was originally incorrect.10 This was the first time one of his personal letters was being subjected to military censorship.

(Field Ambulance sections sub-divided into tent and bearer sub-divisions, with Officers detailed to each and special duties detailed to the men. – Commanding Officer, Unit War Diary.)

April 11, 1916

Rain. We're to leave at 2 p.m.. Must we carry all this? Two blankets? No, as a contrary order was given. Moved off at 3 p.m. along streets of cobble stones, down winding narrow streets. See many young widows with long flowing capes. The children beg for biscuits. A foreign flavour in everything. Took train about 5 p.m. Something new. A long string of cars, every other one marked 'Men' the other, 'Horses'. Why they marked the cars as they did I know not for they were all alike. Thirty of us in a tiny car, large cracks in the floor, the strong odour of horse manure. We have a small flickering light of which K. said we must light a match now and then to see if it were yet alight. No windows. Lay down in blanket and though the lightest I slept warm and well. My first ride in a cattle car. Fellows kick like steers especially when other soldiers pass from the passenger coaches. Woke at twelve and listened for ten minutes to the most awful swearing I ever heard. The horse transport fellows make the place smoke with the bad language.

(Train. Transports and ‘A’ and ‘B’ sections left camp at 3:30 P.M. and march to Gare Maritime and entrained. Men were placed in cattle trucks, 30 to each. Officers had first class compartment in passenger coach. Section ‘C’ and three officers left behind as rear guard; these followed at 8 P.M. – Commanding Officer, Unit War Diary)

April 12, 1916

Ypres, Belgium. In cattle car until about 4 p.m. To eat - 9oz. of canned beef and 3 biscuits. Read Lorna Doone. Off train about 4 o'clock. Hospitals have large red crosses painted on roof and bomb proof huts of sand bags. Unloaded wagons then march some 3 miles through some small villages. We were told that on this road 12 men fell last night. Proved to be untrue for the shells fell short. People look happy. An old lady calmly weaving lace, an occasional building with windows gone, bricks knocked out. When darkness falls star shells [flares] are seen to one side. The first of the real thing, this is war. Within a short distance is the firing line where men are fighting and dying. There have been Canadian casualties within the last few days they say. I hope this horse shoe will not bend. [The horseshoe was a good luck symbol.] If so, God help me. I can scarcely classify my feelings. No fear except when I got a doubtful story of six Red Cross men buried yesterday. One dying in seven months is a more reassuring story.

Still we are here ready for anything. No troubled thoughts or shivering of the flesh as on 13 Jan. We are ready for the work and anxious even. Say we go into the trenches tomorrow night. I have a new mind, take all things, never wink. ‘Oh pack up your troubles in your old kit bag and smile, smile, smile. What's the use of worrying, it never is worth while.’ [words from a popular song].

A low roofed wooden hut with 25 men. Rather close but quite comfortable. Mud, high trees with tuft of branches on top, fertile green fields. Aside from long strings of wagons, horses, fields filled with camps and hospitals, neat little grave yards packed with little crosses, all at peace. Slept splendidly. I sleep next to a negro cook. Carry rations for Sgt. Price11 across mud. Old Fussy [nickname for Sgt. Price].

11 530603, John Finch Price of St. Jerome, PQ.

It looks serious when we see the bricks knocked out of houses from splinters of shells and we listen to the stories which old timers tell for the benefit of the uninitiated. On the whole it is more like a pic-nic yet. The war here is within less than a mile and gives me less anxious thoughts than it did when I was on the opposite side of the world in Saskatchewan.

Fellows in next hut make a terrible row singing injudiciously.

(Belgium. ‘A’ and ‘B’ sections arrived at Remi Siding. Belgium in afternoon and marched to Divisional Rest Station –G.15 C and were billitted. The officers were the guests of No. 5 Field Ambulance. – Commanding Officer, Unit War Diary)

April 13, 1916

The news comes that we are to advance on to the second dressing station. Major: ‘Just keep your eyes open and do your work, never mind the enemy.’ It seems as if it were into the real dangers of battle we were going. 'A' section shakes hands in farewell to us of 'B'. We pack our troubles and smile.

Get mail, precious mail.

A long hard march, hardest yet. The officers make a mistake and lead us nearly a mile out of the way making two miles extra. We make a face and turn around. 2 1/2 hours.

In the first town the windows are half gone from the buildings, marks of bursting shells in walls a few tiles gone but after two years of fighting it does not seem so much. Farmers quietly dray [a two wheeled cart] in their fields, children with their same unconscious laughter play around houses, women do their accustomed labour just as if no guns ever barked death. Auto wagons rumble over the cobble stones, motor cycles fly on their noisy way, army service wagons trot along, troops of infantry march with shovels over shoulder and queer pot shaped, bullet proof helmets [French?] on their way to the trench12. Big guns boom behind us, to the right and left and ahead. We are reassured by the calmness of the inhabitants even though the two years of anxiety and neighbouring death has left its mark. We pass trenches prepared for a probable retreat and the traps of barb wire. A few holes made by bursting shells, six to sixteen feet across.

12 Members of the 9th Field Ambulance were not issued helmets until the end of April.

Spend a night in a most comfortable hut. Divided into sections of six to go to the dressing station. I hope not to go and get my wish and have a splendid sleep. A few wounded we hear about but I do not see. At 1 a.m. I am awakened by the rousing of my bedfellows and listen as a Sgt. describes the horrors he has just seen. He speaks in whispers and is dressed in a foreign looking raincoat. There are candles flickering, blankets over the window to hide light from air craft. It is the hour of midnight when thoughts most readily take hideous shape. I think for a few minutes then roll over on the floor bed. I think of her who wrote me those letters of love and drift off into sleep. Before retiring I write sitting on the floor by candle light. Look outside and see the flash of huge guns light up the overhanging cloud and the constant shooting flares - makes one feel as if it was a noisy thunderstorm - if not for the death. Thrilling. V.C. and men go on up to carry stretchers and the story of the things they saw and passed through come in varied and awful form. If one believed and cared he would die of fear or prepare to pay for his blanket13 in about two days.

13 When being buried under battlefield conditions a soldier's blanket was used as a shroud.

(Belgium. Part of ‘B’ Section and two officers left for Brandhoek in afternoon. – Commanding Officer, Unit War Diary)

April 14, 1916

A day of comparative idleness. Moved to a brick barn to live. Very comfortable and the mice step gently when they make their way across. On guard in the dressing station. See first two men killed by a shell. Poor chaps were in a rest camp quite far back; they were coming out of their hut at dawn when struck. Their ghastly blood flecked features make it more plain the meaning of those booming guns. Handled none too gently, pinned up in their blankets and laid side by side to rest in the soldiers grave yard. ‘In sure and certain hope of resurrection’ read the officer. Oh God may the words be true. If it were not true the horror, the unspeakable cruelty of life would surely banish all joy from the world.

The blackbirds here sing just as joyously as they do in the swamps back at home.

Up until 11 p.m. in the dressing station waiting for wounded to come in. Only one man with Appendicitis. Some do come in after 12. Seemed a rather quiet night from here.

Attended a good lecture by one of those devoted Anglican clergy who follow their men almost to the very trenches.

Saw a helmet torn by a bullet. Hole as big as a fist. The man had another wound in his shoulder.

(Poperinghe, Belgium. Remainder of unit left D.R.S. and took up quarters at 65 Rue de Boeschepe, Poperinghe, replacing No.1 Field Ambulance. One Officer and a detail of men left for Asylum, Ypres. One Officer and a detail of men detailed for duty at Advanced Dressing Station, Maple Copse. – Commanding Officer, Unit War Diary)

April 16, 1916

On duty in the coal house. Others go to church while big guns are making the air pant with bursting shells. Later quiet and we go to a little service in the evening. Simple, very effective. Our hearts go full into the hymns. The old familiar prayers they never were more earnest.

Attended the funeral of three GG [Grenadier Guards] men. The grave yard grows fast.

A most lovely day, warm and quiet except for the shells popping at the many air ships sailing in all directions. They seem never to pay any attention, no more than to mosquitoes and truly few came near. A vicious flash, a puff as of batting white or black, a pop. In the momentary glare of a bursting shell there is something indescribably horrible, worse than the glare of a tigers teeth or the glare of a lion’s eye. Something devilish as if a spark stolen from hell.

The report is that there are some 50 casualties caused by the morning thunder. It proves to be some 2 or 3 slightly injured. The enemy was trying to hit an armoured train and a huge gun but got nothing.

April 17, 1916

Appointed assistant carpenter with Bee and worked at the hospital. I am happy when I can keep busy but when I have time to think the horrors of blood come over me. Blood on the floors, on the blankets, on stretchers, on dead men's faces, on the hands of those who dress wounds and bury the dead, the smell of the dressing of wounds in the air, the thunder of guns which make men bleed, constant stories of death. We were fixing up windows in an old convent which were broken by recent bombardment of the railroad before we came. As a carpenter I shall have no night duty dressing wounds. Thank God. Had a tasty supper of chips, eggs and coffee in a Belgian house.

(Poperinghe, Belgium. April 17 - 27

Divisional Collecting Station located at Asylum, Ypres, for slightly wounded, is situated in the basement; this place is frequently shelled during the day.

Advanced Dressing Station located at Maple Copse is situated in a small low building protected on sides and roof by layers of sand bags. It is reached by a communication trench which opens onto Zillebake road. Its accommodation for stretcher cases is very limited and work is carried on with difficulty owing to the fact that it is a very low roof affair. Patients being taken out on stretchers at night are frequently subjected to machine gun fire by Germans. Patients are transported on trucks along trench tramway 1000m as far as Zillebeke road. Requisition has been made and placed before the Engineers to have the trucks properly protected with steel shields.

Considerable trouble has occurred in transporting these stretcher cases down the trench tramway owing to the fact that ration parties have been using this track for bringing supplies into the trenches. As this is a down track, they are not carrying out regulations as to traffic, for this reason very often out trucks and patients have to be lifted off the tracks two or three times to allow passage of rations. As our stretcher bearers are under machine gun fire, this is a very dangerous procedure.

The Advanced Dressing Station is considered to be insufficiently protected and the matter is before the Engineers.

The number of cases evacuated from Maple Copse vary considerably. The ordinary daily number being about twenty-five. On April 26th, fifty-four were evacuated and on May 1st. fifty-two.

The Divisional Collecting Station at Asylum serves chiefly as a collecting post for sick cases in and about Ypres, though occasionally casualties from the same place are received. All except serious cases are held there and sent on at night with ambulance carrying patients from Maple Copse, or when in sufficient numbers, by means of the reserve motor ambulance kept at the Asylum.

A detail of men are kept at Menin Mill, whose duty is to transfer cases from the horse ambulance to the motor ambulance.

The advanced dressing station at Maple Copse is also used as Regimental Aid Post by the M.Os., attached to different units.

All cases evacuated from the forward stations pass through Brandhoek, where they are distributed to Divisional Rest Station or Casualty Clearing Station. In addition, sick parades are held at Brandhoek every day, cases coming in from different units at rest or reserve.

Headquarters at Poperinghe – this also serves as a distributing centre, chiefly for sick cases reporting from units in and about Poperinghe.

Men of our unit were sent here for rest after so many days spent at our Advanced Stations. – Commanding Officer, Unit War Diary )

April 21, 1916

Good Friday. Still a carpenter and spend 12 hours each day at the Dressing Station. I feed the sick in morning and do odd jobs. At church twice. The story of Passion Week and the life of Christ were illustrated. Touching hymns ‘Holy father in thy mercy...’ A prayer for safety and freedom from danger while guns are banging. We have chips at the house of a Belgian. Many words over the charge of a 5-franc note. Bought handkerchief from nuns, kindly old souls. Capt. Tull complains of a plague of carpenters while trying to sleep today. Cpl., S. opens a can of apricots to my pleasure.

April 25, 1916

Ordered up to the Asylum14. Start at 6 p.m. in a motor ambulance. A fast and easy drive over dusty paved roads. The country is pock marked with shell holes. Ruins, ruins, ruins. The houses all deserted. Some completely knocked to mouldering piles of brick, others with gaping windows and naked rafters. Where one half of the house was gone I saw a baby's cradle in the upper room. The Asylum was a magnificent building of brick, beautiful little grassy court yard with forget-me-nots and daisies. The windows are all gone and not a fraction of serviceable roof is left. In the lovely little chapel the altar partly remains but the head of Christ is gone. One can imagine what a pleasant place it had been. We live in the cellar and sleep on stretchers. A little dark but otherwise quite comfortable. At dusk some shells burst over a small company of soldiers resting and some are brought in wounded.

14 The Asylum, also known as the Heilig Hart Instituu or the Sacred Heart Hospice, was located on the western outskirts of Ypres. It was a large structure built around an open courtyard and had a moderately sized chapel at one corner of the complex. There was a graveyard within the grounds of the hospital which was used from Feb. 1915 to Nov. 1917. By the time the Asylum ceased to be used as a Dressing Station the cemetery contained 256 British, 9 Canadian, 7 Australian, 2 British West Indies. All were eventually reburied in Bedford House Cemetery. By 1918 the German bombardments had reduced the Asylum, as well as the town of Ypres, to little more than piles of brick. After the war the hospital was rebuilt according to its original architectural plans.

Fragments of shells [shrapnel] occasionally drop in our yard. The air seems alive with gun explosions and bursting shells. We feel quite safe. Nothing but a Jack Johnson [large calibre shell] could reach us if we stay inside. Some of the fellows go on up to the mill to help in the rush of wounded tonight. The birds are singing their spring songs as they build their nests in sheltered nooks of the ruins. The sunlight is lovely. I enjoy a walk across the courtyard in the long dewy grass.

April 26, 1916

At the Asylum, reading, sleeping, wandering around the ruins.

The artillery starts early in the morning, a terrible bombardment of the enemy's artillery. The batteries within a stones throw of this building makes us jump when they go off. Huge guns, a flash of hellish fire, the atmosphere cracks like a solid thing, one grips the railing as the concussion strikes, then the peculiar whurring scream of the shell as it seems to bore its way through the air. The sound of the shells causes a strange echoing noise as if the sky was an enclosed dome. Fritzy contents himself with blazing at our aeroplanes.

At about nine hell develops in a small valley to our right. Fritz it seems had not been answering our guns but was busy on our trench. On the distant ridge the shrapnel shells burst with a livid red hue. The effect was awful through the clouds of rolling smoke which soon developed. This with shooting flares, the rattle of hand grenades bursting and the machine guns pecking was awful, thrilling, indescribable.

I stood in an upper window gazing out and pray with a heart beating faint, wondering how it was going with our fellows and wishing evil for Fritz. How could I wish evil and pray? Because evil for Fritz meant the end to these scenes of horror.

Earlier as I stand at the gates a shell bursts near and its pieces rattle on the road just in front of me. I beat a retreat just as another comes and sends things rattling among the ruins. At the front gate I hear some two dozen go over, many not exploding. Their shells make a different noise from ours. It is easy to distinguish ‘going’ and ‘coming’. With each ‘coming’ we crowd in behind the wall until it has passed over. One shell comes pretty close and causes slight panic. I was sitting outside on a bench looking up at an aeroplane with some shells bursting near it overhead. Fearing that some bits might fall upon us I started for the door and the noise of an approaching shell makes us crowd like a flock of sheep before a dog.

I am on guard duty until 12 p.m. Give soldiers water and have a talk with them. Help a sick lad in. Begin to realise that ours really is an errand of mercy.

Lads return early in the morning and describe the battle, how it started and some of the things that happened. Fritz gained nothing by his blowing up of the hill and his attack. Many a poor lad lies cold this morning that was whistling in full manhood yesterday.

Capt. Tull says our cellar has a chance of a million-to-one of being hit by the shells.

April 28, 1916

Two months since I left Montreal. It seems like years. Canada seems like one of those places so far away in time and distance you only just remember.

Now we are at our regular work the time will pass more quickly especially in these perfect summer days. I found a new and pleasant occupation - sketching.

The officer calls us all down into the cellar because of a heavy bombardment which we fail to see or hear. We soon come up again and everyone is hunting for souvenirs. The most plentiful are bits of shrapnel shells. One falls off the roof from a bursting shell. Hamilton got it. I found another bit on the altar of the church.

A wounded soldier tells jokes when one would expect groans. His back was a complete mass of sores, cuts and bruises from the shrapnel. ‘I feel as if an old hen had been scratching for worms on my back.’

A medical man tells me something of his experiences during his 20 months of service. On one occasion, while carrying a stretcher a shell just passed him and tore down a brick wall covering himself, his companion and the wounded man but all come out safe. He believes the war will never be over. Nothing can stop it.

I like these old ruins very much, rather romantic and though the shells give me a start now and then I have no sense of danger.

Pay day, 15 francs.

April 30, 1916

Sunday and on guard. A lovely day with a singsong at night conducted by the Capt. I rescued two books from the ruins. We were in the church, at prayer at 9 p.m. when I got a bad fright. A blinding flash. A shell seemed to burst right over my head. A shower of bits of plaster pour over me as I sprang for safety behind the altar. With fast beating heart I return to the cellar where all was excitement. A few moments later a crash as a shell struck the building just overhead. Bits came in through the upper door and hit the stairway. It hit the wall about 12 feet from the door tearing a great hole and knocking bricks and debris into the tea room where a number of chaps were sitting. It gave them a most hearty scare. It just passed by our ambulance in which was a wounded officer and a number of men.

(Poperinghe, Belgium. Two shells came into Asylum courtyard and punctured our water cart (first casualty) and barely escaped ambulance with full load of wounded. – Commanding Officer, Unit War Diary)

May 1, 1916

Read the Testament after work. Warr and I wore our steel helmets while on duty. We go out with reluctance into the court yard. We see shells kicking up a fearful dust in __?__. We see Sgt. M15. dodging around corners. No mishaps from last night’s shells.

15 530576, Cecil Norman Mayoss of Southampton, England.

At 12 p.m., after I had undressed and into a delightful snooze a call was received for stretcher bearers for the Mill. We go out in the motor ambulance. These machines fill me with admiration. A purring sound, a passing shadow, a cloud of dust is all you get as one passes you. Up through the ruins and desolation. The most fantastic forms. Huge buildings, fallen all but one wall and that standing with gaping window holes or shell punctures. A corner of a wall here stands as a jagged tower. Beautiful arched windows and doors broken and torn. Piles upon piles of brick. Here a faint light through a blanketed doorway, there the remnant of the tower of the beautiful cathedral. The public buildings gutted, cracked, punctured, torn. Piles of ruins. A year and a half ago this was a fair city full of life but the war sport passed and now this ...

At the Mill we stop. A room some thirty feet long and ten feet wide. It is high enough to stand upright in the middle and is made of an arch of heavy iron covered thick with sand bags in an old building. We pass into it through the two doors covered with blankets. Within the usual semi-darkness of candle light, the tins of jam and biscuits, blankets, stretchers, boxes of tobacco, smoke.

Four fellows are sitting about chatting. One is making cocoa for the sick that will come in. There had been a big scrap on and a rush of wounded is expected. Some 60 we hear. The walking patients with small wounds come in and sit along the walls telling the story of the fight and how they or their companions were hit. ‘Are we down-hearted? No.’ [words from a popular song] is their bearing.

Then came the horse wagons bringing the wounded from the advance dressing station over the shell punctured roads down this far where we have to change them to the motor ambulance which will carry them on down. Gently, silently we lift them out of the wagon and into the ambulance or lay them on the ground to wait for the motor to return. One fellow was moaning and calling to his mother or praying ‘Oh God’. Mothersill16 talks to him and tries to take his mind away from his wounds. One fellow had died on the way down. They take him to one side and later bring him into the dugout to search for name papers and valuable to send home. We pass among them tucking in their blankets, giving water and cocoa, speaking words of encouragement. The flash of the star shells gives a dim light for our work aided by the stars. The machine guns rattle fitfully.

16 530588, John Elmore Mothersill. At the time of his enlistment in 1916 he was an ordained minister at Taylor Presbyterian Church in Montreal. He served as a Private with the 9th Field Ambulance until 1917 at which time he received his Commission and served with the Canadian Chaplain Service. He suffered exposure to poisonous gas and was invalided out of service. After the war he settled in Kirkcudbright, Galloway, Scotland where he served as a minister with the Church of Scotland. He died in the early 1970's.

The light of day began to come slowly before three. In the last load we lift out a German officer and two wounded men. The officer raises his head to watch what we are doing with him.

We go back in a horse ambulance through the ruins now seen a little more clearly. How slow it goes.

[At the Asylum] Tucker is on guard at the door looking so rustic that I do not know him. I tell the stories heard during the night and go down to sleep. A full night.

(Poperinghe, Belgium. 68 patients were cleared to M.D.S. Brandhoek. The men worked well and we feel proud to have been able to get so many in one night and leave the .D.S. ‘cleared’ at dawn. – Commanding Officer, Unit War Diary )

May 3, 1916

Very quiet day. Read the Latin text of St. Matthew. Jesus seems to speak so many awful words. It is the conversations between him and the Pharisees that is most often told. One is so deeply fearfully impressed with the earnestness of life as one reads his words.

We hear that a mail wagon was blown up and think this may account for our lack of mail.

May 6, 1916

A terrible night for our transports. Germans swept all roads with shells. Many stories of narrow escapes and disasters. S. Jones claimed he had a close shave or half a dozen close shaves.

Fritzy shelled the Asylum. I was in a distant corner at prayer at 8 p.m. when the light of an exploding shell flashed around me. Until nearly 12 p.m. shells were bursting around the building. We were ordered down into a cellar by Capt. T. and it was no hardship. I was in the Dispensary listening to soldier's stories and reading when a shell struck and knocked down some brick. The fellows were restless, rather afraid, hugging the sides of the building and the places under the iron beams. A shell hit with the thunder of a falling building and it seemed to last about a minute. There was a wild rush for the officer's room which was more secure. Men flopped flat on the floor and rushed in a way that was really laughable if one had been free to look at it in this way. A brick fell down through a window with a cloud of dust. Later I slept while waiting for the ambulance to take me away at 3 a.m.

May 7, 1916

A most beautiful morning as we came down the tree lined road. Nothing to recall the bombardment of last night except a dead horse by the road way. To Brandhoek and to Pop [Poperinghe]. Got a pass and Bert and I go out into the country for a long walk. Delicious to be out of the sound of guns. In this country way there is no indication of the war, peaceful and spring time beauty. Picturesque houses of brick and tile among the green of grass and trees.

May 8, 1916

‘On kitchen’ [duty]. A walk in the evening poking our noses into shops with much satisfaction. Spent some money.

One hears something one moment which makes one fear the long, long continuance of the war and the next, something which causes you to go to the other extreme.

The talk of the men fills one with utter disgust. There are to be 60 ‘women’ sanctioned by the government yet we are here to fight for the ‘right’.

May 9, Monday, 1916

Poperinghe

A day free. Go with Matthews17 to Coubert Monastery, some 14 miles tramp. A great old place of some 200 years on a hill along which one can see nine of the old long armed windmills. The monks were sharing the monastery with the troops. We see one old fellow in his ancient garb, gown and rope girdle, bare feet, cowl and black beard. Go through the sick wards where soldiers lay on stretcher beds. Have tea at a farm house, eggs, bread and coffee. Have interesting time trying to get her to understand my French which is filled in with English. She explains ‘Me Belgium, me married, husband at Front.’

One fellow was packing up his friends' clothes. The friend had just died. He was not talking much to the men around as if feeling much and saying little. As he went out he said ‘Oh well, the world is mad. God is good. I hate it all but I'm going to stick it’.

Sgt. M. came up to the Asylum trembling in fear of the shells. With much hesitation he made his way out to the court yard to wash. Graham18, taking in the situation, watched his opportunity and threw out on the cobble stones a great tin can and then disappeared. Just how far Sgt. M. jumped has never been agreed upon.

Men under fire naturally act in peculiar and different ways. Mr. Muir19, a man whom I have never heard swear says that when the shells burst around he can't contain himself but must curse till things clear.

17 530687, John Matthews of Cheshire, England.18 530542, William Graham of Cluckmannan, Scotland.

19 530671, David Holmes Muir of Westmount, PQ.

An officer, wounded, would take no medication until the men were served and then only when he was sure there was enough for all. He who is first is second to all.

May 11, 1916

Another walk to Mont des Cats. The highest point in the north of France from whence you can look down on all the cities of the plain even to the sea. A wonderful view of green fields, hedged trees, wind mills, houses and, in the further distance, the towers and steeples of distant towns. Much of the country has been fought over though showing little of it now. Saw German graves one of which they say is a Crown Prince.

A valley of green and hill side blue with hyacinths.

The Belgian women almost always speak to us though other soldiers that we meet seldom do. Get some chips with Matthews. Three Imperials [British soldiers] are present. They talk filthy to the women and hit one of them with a rap on the hips. My blood boils at the disgrace to the Khaki [uniform]. Some of the women seem afraid to speak to us. Paid 11d for chocolate. No. 9 Field Ambulance are called chocolate soldiers by the Imperials because they are seen more often with a piece of chocolate than with Extra Stout [Ale].

May 15, 1916

Moved to a camp just outside town. Hate to move. Our old kit bag is heavy. I was sitting, reading quietly, when suddenly a great commotion and a storm of language like I had never heard before. It proved to be the Sgt. Major getting after us to clean up everything for the arrival of No.10 [Field Ambulance]. We go for a walk in the evening into country ways and the night is full of the roar of guns. Nicely asleep when a bunch march in from the corps with roaring laughter and loud talk. Wake us all. In the morning we hear that an aeroplane dropped bombs nearby. A wild commotion which I did not hear. Some said they heard things fall, a bit goes through a tin roof etc. Couldn't see anything.

On a march we move as if we were new recruits. The Col. gives an order, the Sgt. Major thinks he made a mistake and gives another. A fine mix up. Made all the officers angry.

(G15c. Whole personnel and equipment moved to G15c – map 28. This is a very suitable camp for a Field Ambulance. Men are accommodated in wooden huts. There is room for about 60 patients also in huts. The Officers quarters are also very comfortable. – Commanding Officer, Unit War Diary)

May 16, 1916

Went a few paces away to read and write and then could not be found when wanted for duty. On pay parade Sgt. Major called me down and I protested. Some words and much heart. Every Sgt. is as the Pope in his infallibility. Perhaps I was slightly at fault for I wanted to write and one does get lazy.

A bath parade on which the two main topics of converse were lice and the end of the war. ‘Are you crumbly [infested with lice]? Not I - yet! ‘

A lovely walk in the evening, a R.C. [Roman Catholic] service, a valley filled with sun set gold. A country very beautiful.

The name of our hut is Optimistic Hut. I have joined a pioneer squad with Bee. A bomb proof job. I so wish it was. Early in the morning a great commotion caused by hostile aeroplanes. A bomb dropped near with a great roar but I slept through it all.

This diary follows no rules of composition I know. I started out in the evening and end up in the morning.

Each morning Fritz comes along with his aeroplanes and bombs our fellows. Say the Britishers can't get up early enough to keep him away. It is most unpleasant to hear those bombs go boom down here when we are supposed to be at rest and out of danger.

(G15c Good deal of Bombardment by aeroplanes in early A.M. of this district. – Commanding Officer, Unit War Diary )

May 18, 1916

A stand to [an alert]. This night it fell to my lot to lay in the middle of the bunk made of six blankets on the floor. Wilson on my left, Bert on my right. The lights of the candles were blown out at 9:30.

May 19, 1916

Reading of army art during which men amuse themselves tickling each other with grass. I said that I don't feel so bad about giving a sermon now.

An inspection of gas masks.

Walk to an old wind mill for grinding wheat, rustic enough, surely. Shakes as we walk up the stairs. A fair hair girl lowers the bags. A pretty picture against the Belgian green and blue. The old, old mills with its long awkward arms and ancient machinery. The two wheeled cart with huge, slow moving, good natured horses fastened with a chain and the sweet little maiden pulling on the rope in the door.

A terrible misfortune. Stumbled and spilled my pudding at noon.

Had a theological argument with Wilson20. Finished reading Battle of the Strong.

A bullet went through the cookhouse roof just at noon giving C. Davis21 a scare. A man in our sister corps reported wounded near the Copse.

20 530659, Aaron Porter Wilson, of Montreal.21 530528, Charles Freeman Davis of Freshwater, Nfld.

The cookhouse stands to the east of the huts. A corrugated iron roof covers it. The sides are of boards but left open on two long sides to give air and allow smoke to escape and relieve the sore eyes of the fatigues working inside. Orders give times for meals but at supper fellows are playing ball, horse-shoes, reading, writing, the time is not noticed. ‘What's that? Supper is ready?’ A commotion, the ball is dropped, books shut and crammed away someplace, then flying figures jumping sidewalks and ditches, cramming into hut doors and fumbling among the hundred and one articles of the kit for the mess tin. The same rush to get early in the bread lines. In a very few minuets the long line is formed with jingling mess tins. The boys play, there is an occasional oath. To be late means twenty minutes wait for supper. Then slowly, so slowly, move forward step by step until the bread is reached ready cut on the table, the basin of cheese, the spoonful of jam and the tea. Old tea grannies we are! Supper secured, a shady place found and super in the mess tin on the grass with gossip. When will the war end, discussions, etc. All food gone the mess tins must be swept and garnished with sand and water from the water tank. Run to get supper but go very slowly and regretfully to washing of the tin. Here ‘We're in the army now’ catches us with an unpleasant hitch in the side.

May 20, 1916

Work on the cook house. Have a terrible struggle not to dislike C. Davis and be cross and irritable at many things. An attack of the blues, fought with the help of God to some success. A letter from Leslie in Saskatchewan. A store keeper is surprised that we, being thirsty, ask for water not beer. A scrap with MacIntyre and Tucker in the blanket.

May 22, 1916

Early last evening a hush seemed to fall over the whole camp. A whisper of a calamity. Was it true? It could not be. With some questioning it was confirmed. Our officer who was with us yesterday had been killed up near the Copse. An ambulance had been sent for his body. The first casualty had occurred in our own corps and that of Capt. Waterson. The sadness of the thing followed us in our walk and weighed heavily on our attempts to have a pleasant talk. As we were lying down to sleep Thomas came to the door. More sad news. McGurty22, his batman, had also fallen. His brother23 is with us still.

22 530645 Pte. John McGurty, age 24, son of Catherine McGurty, Cote St. Paul, Montreal, KIA 22 May 1916, Panel 32, Menin Gate, Ypres, Belgium, no known grave.23 530665 Pte. Albert McGurty of Montreal.

The funeral was for four o'clock. A voluntary parade. All special duties were called off so that all might go. At three o'clock we fell in. The officers and part of the men of No.10 were present. In a little hut, roughly built of tar paper lay the body. The coffin was neatly made of pine boards, unpainted. With hats in our hands we filed past our captain who lay like a warrior taking his rest. A warrior against death wrapped in the soldier's gray blanket. His boots were muddy as if he had been walking far. A single, small wound disfigured his face.

The lumber wagon with small black platform fastened and a team of fine black horses drew it. We did our best in the drill and the march. Some dozen officers are present. When everything is ready, six men carried out the body on their shoulders. It was covered with the flag and bands of flowers. As it appeared we were called to the General Salute which we held until it rested on the carriage. Order of March was formed and we moved off at the Slow March which was quickened to the Quick March outside the gate. There was no sound of music since a medical corps has no band. Each soldier, especially noticeable the Belgians, salute the body as it passes. The pungent dust filled our nostrils, the weather was hot and the wagon rumbles over the cobbled stones. The natives stood at the doors gravely chatting. Some two miles brought us to the cemetery. Once there we are lined up and listened to the burial ceremony conducted without a book by a Major Chaplain. A Methodist we thought. The officers all marched past the body with a salute as they passed just as devout Catholics bow when then passing the alter. Then the bugler was called to sound the Last Post. This call is always heard after darkness has fallen and when we retire. In this connection it was most impressive and made the lump form in our throats and the tears come near the surface. ‘Lights, lights out.’ Finished the bugle. Surely lights out ---.

Away again at the Quick March back to camp. No tears had fallen and we thought the most of ourselves. Who would be next? Still we were sorrowful for our captain and talked much of how it had happened. He had gone to relieve a doctor of another unit in the trenches and while in a dug out a shell had struck and killed five out of the six. Ralph Connor's24 batman25 was killed. He himself had just stepped outside the dugout and thus saved his life.

24 Ralph Connor was the pen name of the prolific and popular writer Rev. Charles W. Gordon. In 1916 he held the rank of Major and was serving as chaplain with the 9th Brigade, 43rd Battalion, Cameron Highlanders of Canada.25 421050 Pte. Edward George Ledger, 43 Batt., age 41, of Winnipeg.

(G15c Horrified this afternoon at 5 o’clock t learn from A.D.M.S. that Capt. Waterston and Pte. J. McGurty were killed. They were in a R.A.P., Sanctuary Wood, dressing a wounded man. A direct hit was made on the dug out and all occupants (six) were instantly killed, except one. Great regret felt by all over this sad loss, our first Battle Casualty.

Capt. Waterston’s body brought in early this A.M. Pte. McGurty has been buried at Maple Copse by Major Ralph Connor.

Capt. Waterston buried 4 P.M. by Major Beattie at Reninghelst. The whole unit attended as well as deputations for No. 10 Field Ambulance, No. 1 Field Ambulance and No. 3 Field Ambulance, also Col. Frotheringham, A.D.M.S. 2nd. Division. Beautiful flowers from No. 10 and ourselves. – Commanding Officer, Unit War Diary )

May 23, 1916

I saw Armstrong26 on the wash house job. Into studs up to his elbows and singing ‘Will never let the old flag fall’ in a voice none too musical. Today nails were scarce and I learned a new trade. I hope though not to be compelled to put in practice in civi life. Competitors will not likely be many. I was an ash picker.

26 530507, Wilmer Coulter Armstrong of Shawville, PQWe had an issue of chewing gum.

May 24, 1916

A sports day in Pop arranged by G.M. No.9 acquitted itself well and won several prizes. The crowd of Canadians was so big it was impossible to see satisfactorily. While bloody war was raging 15 miles away we were cheering with the usual enthusiasm over a base ball match.

Dinner of chips, a bath and a walk about town. Wilson on guard. A very nice time with usual sports day headache at night.

May 25, 1916

[A typical mornings routine]. Perhaps with half a sleepy eye I have seen the daylight shinning through the door. Perhaps I have heard, with a sleepy ear, the whurr of hostile aeroplanes or our own and the constant air battle. At six the guard comes in to call the kitchen fatigues more or less noisily. I wake too and know I am to have half an hour longer when the bed is so comfortable just before one must leave.

All too soon the watch shows 6:30 and I remember that 200 men must wash in four basins and the early bird catches the dish. The Orderly Sgt. to comes to make sure all eyes are open with a gentle push with hand or foot on the blanketed figures on the floor. Sometimes this is accompanied with word battles but 'tis no use to complain against Fate or the Orderly Sgt.

Up, dress, blanket shaken and put on the roof to air. The water is a problem. There are three sources of supply. A well with a broken pump; a frog pond which receives the drains of the wash house - but we must not wash here, so the Sgt. of Transport says, for he waters his horses there; and the water cart but another Sgt. has ordered no water to be taken for washing. What is one to do? You do as you wish and try to appease any Sgt. who runs athwart your way. None are around in early morning. We wash in a cut oil can and shave in cold water. This done we have physical drill by Sgt. A. We like it best when it's muddy and they let us off. The rusty muscles must work and the toes must be touched. Legs stiffened with yesterdays run must run again. This spasm past - a run for the breakfast line-up occasionally with a book to read while waiting.

May 27, 1916

On Saturday the three of us went to Pop. Saw a foot ball game, had picture taken, saw a picture show. In picture show driven to desperation. I tried to reprove an Imperial for his vile language. It was not that I loved his soul but he made one uncomfortable. Spoiled the picture for me. He told me I should be .... I know not where. He would quit when he wished. He quit but somehow I felt a failure and spoiled the evening walk home. I was in the blues. These blues, which I keep away quite successfully, sometimes grip hard. Am I a failure for all time? Well, if I fall in battle she will never think so.

Met M. in the evening and showed him B. Perley's letter re. keeping our chairman in touch. Had a talk on spiritual things which did me much good and I hope him also. Not so bad a day!

May 28, 1916

Church parade. Service was under a rather hot sun by a clergyman from Quebec. A simple little Anglican talk. Enjoy the Holy Communion service after. The priest robed himself before us and good Methodist brethren had to force below a wayward smile27. Men of all classes were among the some 20 present. Men of clean lip and those whose mouth often utter the filthy blasphemous things. Men of all congregations were gathered in. Praise God for this freer spirit.

Wrote six letters under an apple tree. Tried to find Wm. Creik. Almost taken for a spy because of my many questions. A splendid view from this hill top above the town where so many Canadian regiments are encamped.

Fritz shells Pop. From about 6 to 12. Bee, who had stolen down into town without a pass came back with eyes big but still smiling like a boy just escaped from a policeman. A shell had struck the house next to him and he had the dust of the explosion upon him. In bed we lay counting the shells going into Pop. Most of them were duds. We hear the gun go, the flying cry of a big shell, a fire cracker explosion or was it the noise of its fall only. Such a dead shell we call a dud.

Early in the morning a terrible commotion in the air. All kinds of guns used in the business were going. Roll over again and sleep and let men who fight, fight on, and let me, when I am supposed to, sleep. This is of a certainty a 20th century experience. A sleep under a battle field. That battle field the clouds and its warriors on wings shooting bullets twice as quickly as a watch ticks.

More about Bee. He had seen a sign on the Talbot house28 ‘Come out into the garden and forget the war’. He did and soon after a shell struck in the garden knocking him flat down and covering him with debris though he was on the far side by the wall. Another fellow in the house was struck.

27 Methodist of the day considered the robes of the Anglican priest to be overly flamboyant.28 The Talbot House, located in Poperinghe, was established and operated by the Anglican Church with the aim of providing the troops a quiet refuge away from the war. There is a large chapel on the upper floor.

May 30, 1916

Bath parade. We lined up with towel in hand and march off into Pop. Arriving at the baths we march into a large yard the back of which is filled with lines where girls are hanging out socks, shirts and underwear by the mile length. We enter a hut made of canvas, a form running down the center on which to sit while disrobing. All outer clothing is here taken off and tunics carried in the hands. Twelve at a time we enter and strip leaving dirty clothing on the floor and hanging tunic and trousers on a cross bearing a number which must be remembered. This done we pick up our boots and towels and go into the bath room. Here we see twelve tubs above which is a rather meagre sprinkle of warm water. Soap provided we indulge in luxury more delicious than the perfumed fountains of the ancient citizens of Pompeii. The stone floor, inevitable in Belgium, feels cool to the newly washed feet. Dry on our dirty towel, into a dressing room where another luxury awaits us in the form of clean socks, shirt, towel and underwear. Happy is the man who gets a shirt of some certain color and shape in which he will not loose himself in empty folds. I should not prefer, if I had my choice, the garments of a Grenadier Guardsmen [generally very large men] washed last week. From a hole in the wall ones tunic and trousers comes back to you hot. The cross is suggestive of a grave but it really is alright. It marks the grave only of nameless, little, unwelcome creatures. In the process of the bath they have been crushed by mighty giants who with monster eyes search them from their dug outs and advance trenches in shirts and underwear. Deserted by these same giants whose companionship they have so persistently clung after plenteous feasts and generous hospitality. Drowned in falling water, roasted even in their homes in their tunic palace. Now the monster giant goes with, he hopes a least, none of their company. We dress, fall in and go back through the dust, heat and grime of the main road.

May 31, 1916

While writing a letter saw an observation balloon adrift and in the same darkness German shells were bursting by the scores. Looked like the flash of fireflies. I heard the men had descended in parashoots when it broke loose. Davis said if he were there he would prepare for a hasty trip to Kingdom Come. It was an impressive thing to see there drifting in the darkening sky with certain destruction flashing on every side. If not by this shell then by that. Like a sinner at the end of life, drifting into darkness and death.

Talk not of your Heroes, the men of long ago

For we have men much greater which I'll proceed to show

Men noted for their Valour, their Hunger, Talk as well.

And as you seem impatient, their exploits I will tell.

A valiant man who knows all things as sprightly as a lark

Who'd end this war, right at our door if left to Private P-k.

But he has gone to D.R.S. Case hopeless too they say.

He's got shell shock, an awful knock, it fell a mile away.

Then there is the one, who saved a gun, a Battery so do tell.

He's modest, quiet, never talks, his name is Private R-l.

When shells are falling just like rain, one fell, and no one tried to stop it.

He caught the shell and threw it back and killed the man who shot it.Thus__?__ a brave N.C.O. who the Copse was sent

When shells did burst, its ‘Safety First’ says our bold Sgt. A---n.

Oh my poor back, I'm on the Rack, who slaps me woe betide him.

He rode the track, when coming back whilst wounded walked beside him.Another one has stripes quite three, he's good with Pill and Potion.

To Do or Dare, He doesn't care where, for danger he's no notion.

Too proud to fight, though in the right, the Allies under rates

But then its plain, should he explain ‘I'm from the U.S. States.Then we have one, the Son of a Gun, He's in our Cavalry too.

He's got the spurs. He's got the legs, for letting shells go through.

We've Shrapnel Pete with rubber feet, got souvenirs by the ton

Old iron, bits of shell he gathers one by one.But why go on, we're Heroes all, and when stood up in line

The Boches fear, the Allies cheer, long live the No. 9.

June 2, 1916

A Stand Down. Went on a walk to Zellebeke. I have neither the time nor the inclination to write these days. I believe I shall remember the red of the beautiful evening sun as we march along, strung out is sixes, 50 feet apart. We pass shell holes, dead horsed and pass a quarter mile where huge trees were broken off, their branches and leaves covering the road. We wondered if we should see the sun again for, by the roar of the guns and the stories of awful things we had heard, we knew that a hot time faced us. Nearing the Asylum high explosives burst a hundred yards away sending a piece of shrapnel to land at Bert's feet frightening him. Then our walk close up to the Asylum walls and our retreat inside in great haste. We rest there and on with the stretchers.

(Near Poperinghe, Belgium, G15c, Sheet 28, 2 P.M.

Ordered to hold unit in readiness as many casualties were reported from the front.

4 P.M.

Ordered to send Bearer Divisions of the three sections and three Officers to report at #10 Field Ambulance, M.D.S., Brandhoek, also three horse ambulances, five motor ambulances and all available stretchers (100).

5:30 P.M.

Orders carried out. The detachment under Major Bazin, Capt. W.G. Turner and Capt. F.J. Tees.

6:30 P.M.

Ordered to detail extra Officer and all available men and ambulances to Brandhoek.

7:30 P.M.

Order carried out. The detachment, twenty-four men under Major W.B. Howell with three light horse ambulances and one motor ambulance. The men were sent up the line as follows;-

30 men under Capt. Tees to Zillebeke Bund.

36 under Capt. Turner to Asylum (Ypres) and Mennin Mill

Balance remained at Brandhoek Dressing Station.

The motor ambulances plied between Hell Fire Corner, Mennin Mill, Asylum and Brandhoek.

Horse ambulances from Zillebeke Village to Mennin Mill and Asylum.

3 June

The detachment worked all last night and brought in hundreds of wounded, so that No.10 Dressing Station at Brandhoek became inadequate. This unit was then ordered to open a Dressing Station in the Church Army Hut. The hut was very suitable for the purpose and in a short time Major Bazin had it fixed up so that it looked as if it had always been a Dressing Station.

Every available man was pressed into service and the wounded were carried in all day. This was remarkable considering the ground covered. The Drivers of the horse ambulances form Zillebeke village to Mennin Mill did their work continuously under shell fire and as this road is under full view of the Germans from Hill 60, it is remarkable that we had no casualties amongst these men. They deserve the greatest praise. Motor cyclists did well. Booth were hit while on duty. The drivers of the motor ambulances are also deserving of great praise. Their work was done also under shell fire and practically every ambulance was hit. The drivers had miraculous escapes and only two were minor casualties.

4 June

The whole staff worked all night and this morning things were quieter.

Capt. Tees and those with him have done great work. They cleared 1100 men in 48 hours. The wounded were carried about 1200 m. over ground which was constantly under shell fire. Some wounded men were killed whilst being thus carried but fortunately none of out bearers were hit. The dressing of the wounded by the M.Os., was also under fire.

Capt. Turner and his men worked well at the Asylum, Mennin Mill and up the Mennin Road.

This ambulance assisted No.10 Field Ambulance in its work of evacuation in addition to the 594 cases put through our own books in the past two days.