![]() MARTIN MIDDLEBROOK

MARTIN MIDDLEBROOK

How a Memorial to the 12th (Eastern) Division

Dead of the Somme

found its way to British Columbia

![]()

One of our three daughters lives in Canada - in Calgary, Alberta, just east of the Rocky Mountains. For our third visit to her family, in May of 2007, we decided not to fly direct to Calgary as before but to Vancouver and then drive right across the Rockies, through the Province of British Columbia, to Calgary. The sun shone all the way. We had no problems. It was a good trip.

Most of British Columbia is mountain and forest but half way across the Province is the Okanagan Valley - a fruit growing and lake-land holiday area. We broke our journey and spent two nights at a Bed-and-Breakfast place at Kelowna, the main town of the valley. This gave us a full day for sightseeing.

Kelowna has a cultural area. After studying a plan, Mary and I split up, she to go to the Art Museum, me to the Okanagan Military Museum - a modest establishment but with a warm welcome. Officially it was closed that day but a friendly young man, Keith Boehmer - one of the Curators - allowed me in when I explained that I had travelled several thousand miles.

I received a most interesting surprise. Standing in the Reception Area was an imposing wooden cross - brown, mellowed oak, more than eight feet high - with painted inscriptions showing that it was a memorial to the men of the 12th (Eastern) Division who had died on the Somme in 1916. Having a strong interest in the Somme since a first visit forty years ago and a similarly strong interest in the organisation of the British Army in the First World War, I naturally asked how a memorial to an exclusively United Kingdom division came to be standing in a museum in the middle of British Columbia.

The description of the journey of that memorial, from the Somme to Kelowna, is the story I am going to tell.

The 12th (Eastern) Division

In August 1914, Britain possessed only six infantry divisions, earmarked as an Expeditionary Force in the event of war. Roughly the equivalent strength of infantry was scattered around the globe garrisoning the far-flung British Empire. When Lord Kitchener became Minister of War he decided that the country needed a much bigger Army and the Government sanctioned the creation of a further thirty divisions composed of civilian volunteers. Thus was formed the famous Kitchener New Army that would eventually provide the main strength of Britain's military effort.

The new divisions were formed in five batches, each of six divisions. The first two groups - the K1s and K2s - were recruited from the traditional county regiments in the regions of Britain, except for the sixth division in each group which were formed from the Light Infantry and Rifle Regiments. These were the first six of Kitchener's new divisions:

9th (Scottish) Division

10th (Irish) Division

11th (Northern) Division

12th (Eastern) Division

13th (Western) Division

14th (Light) Division.

They were informally known as 'The First Hundred Thousand'- a title of much pride because the members of their units were the first flush of volunteers responding to Kitchener's appeal for men in what was perceived as the country's hour of need with the German Army sweeping across Belgium and Northern France at that time.

The 12th (Eastern) Division was typical in every respect of that famous group of divisions. Their twelve original infantry battalions came from the regiments traditionally raised in the counties of East Anglia, around London, and in South East England - Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, Middlesex, Berkshire, Surrey, Sussex and Kent. A thirteenth battalion, the 5th Northamptons, soon joined to serve as the division's Pioneer Battalion. The Artillery, Engineers and other supporting arms mostly came from the same areas.

The first six of Kitchener's new divisions were considered sufficiently well equipped and trained to be dispatched on active service in the spring and summer of 1915. Three of those divisions were not sent to the Western Front as their members had expected, but to the Mediterranean where they took part in the Gallipoli Campaign. The 12th (Eastern) Division considered itself fortunate to be one of the three divisions sent to the Western Front, crossing to France at the end of May 1915.

The Battle of Loos, 25th September - 15th October 1915

After nearly four months gaining front line experience mainly spent on the relatively quiet sector of Ploegsteert Wood in Belgium, the division was judged ready to take part in a major battle and moved south to France to take part in the Battle of Loos.

This British attack was by far the greatest British effort on the Western Front so far in the war, its scale made possible by the arrival of the New Army divisions. Five of Kitchener's new divisions of citizen-soldier volunteers would take part but the 12th (Eastern) Division was not called upon for the opening phase.

The 9th and 15th Divisions - both Scottish - took part in the attack on the first day. Both divisions captured their objectives, although some of their gains would be later lost to German counterattacks. The Scots' successes were so costly, however, that one brigade had to be disbanded because there were not enough Scots reinforcements available. (That is how the South African Brigade became part of the 9th Division.)

The next New Army involvement came with the commitment of two further divisions - the 21st and the 24th (regional titles had been dropped in their third batch of New Army divisions) - were rushed up to the front on the first night; it was intended that they would be pushed through a non-existent gap. These divisions had only recently arrived in France and had never even experienced trench-holding duty. They were overwhelmed and scattered by a German attack early the next morning.

It was in the aftermath of these dire first experiences in battle of the New Army that the 12th (Eastern) Division came into the line on 1st October. The main fighting was over and the division was given the task of holding what had become the new British front line south of Loos village in what was known as The Quarries sector. Its duty was to consolidate the line, to improve it by making minor attacks, and to beat off similar German attacks. This was all achieved satisfactorily, but the attention had lifted from the early advances and there was no glory to be had for the division in the Battle of Loos.

Instead, there was tragedy. On only the second day of the division's presence at The Quarries it lost its commander. Major-General F. D. V. Wing had completed the division's training in England, brought it to the Western Front and commanded it successfully for the past four months. On 2nd October, while visiting the division's artillery positions, a German shell burst killed him. He was replaced by Major-General A. B. Scott who was transferred from the command of the artillery in an Indian Division. General Scott was to be more fortunate; he would remain in command until rested in April 1918.

The 12th (Eastern) Division remained in the line in the Loos area for the next five months, much of the time in the sector known officially as The Hohenzollern Craters because of the blowing by both sides of many small underground mines there. The division's infantry had constantly to fight vicious little actions to take or retake the craters or the intricate trenches that meandered through the crater field. It was a long, steadily costly campaign.

The period did, however, bring the division its first Victoria Cross, won by Corporal W. R. Cotter, 6th Buffs (The East Kents), a native of Folkestone. Cotter was a 33-year-old Reservist, a real 'old soldier' who had a glass eye - the result of a long past pub brawl - but who had been accepted for service in 1914 despite that medical deficiency and had helped train the 1914 recruits. Corporal Cotter had a leg blown off below the knee and both arms injured in one of the trench fights, but he remained in command of his men for a further two hours and helped them beat off German attacks. Unfortunately he did not survive the subsequent journey to the medical station.

In April 1916 the 12th (Eastern) Division was relieved from its long association with the Loos battlefield. In just under a year of front-line service it had suffered 8,604 casualties, a figure that meant that the infantry battalions had lost at least half of their original members. The replacements were still volunteers, however. Unlike the New Army Scottish divisions at Loos, there were still sufficient volunteers from the Eastern Counties to replace the casualties. The division had performed well, but it had not had the opportunity to show its quality by success in a major action.

The next two months were spent holding 'quiet' trenches, absorbing the reinforcements and training. The 12th (Eastern) Division was being 'fattened up' for the next big battle.

The Somme - An Exciting Plan

For the British Expeditionary Force the year of 1916 would be dominated by one huge battle - the Anglo-French offensive on the Somme.

It had been planned that the two armies would contribute equal numbers of men but the German attack against the French at Verdun earlier in the year reduced the French ability to provide their full share and also forced the British to bring forward the opening of the battle by about six weeks. The British had no trouble finding the men; the last divisions of the New Army were in the process of arriving. The later arrivals - the higher numbered divisions - had not been able to build up much active service experience, but they were still made up entirely of volunteers and their morale was exceptionally high.

There were good prospects for the forthcoming offensive. The British had more than twice as many men as at Loos. Guns and shells were available to fire a much longer bombardment. The frontage of attack would be twice as long. On the British immediate right the French, although depleted in strength by Verdun, had the reputation of being seasoned, professional troops. The attack was talked of as being 'The Big Push' and there were hopes of at last achieving a decisive result. Optimism was rife.

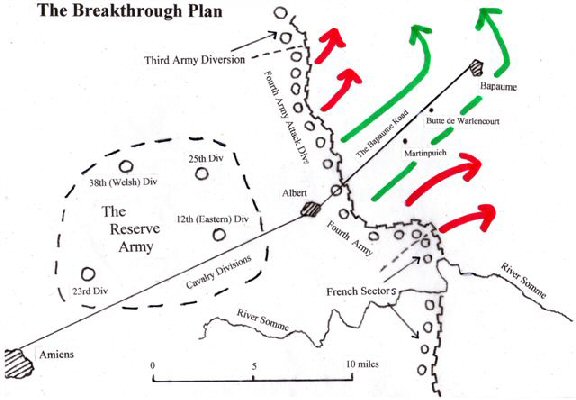

The 12th (Eastern) Division was allocated a particularly interesting role in the unfolding plan.

The initial attack was to be carried out by General Rawlinson's Fourth Army. The centre of its attack front was astride the old Roman road that ran from Albert, just behind the British front line, straight on to Bapaume which was nearly ten miles behind the German front line. Just behind Albert was assembled a separate force made up of three cavalry divisions and four infantry divisions. This was a new creation - The Reserve Army. Its commander was Lieutenant-General Hubert Gough, known to be one of the most thrusting generals in the British Expeditionary Force.

The role of the Reserve Army was to push though the centre of the attack front as soon as the Fourth Army divisions had captured the German front line trench system and created a gap. It was hoped that this could be achieved in two days. The Reserve Army would then exploit the opening, push though to Bapaume, then swing north to outflank the whole German front line in that area and possibly cause a German collapse. Most of the British soldiers preparing for the battle knew of The Reserve Army and its role. They called it 'Gough's Mobile Army'.

All four of the infantry divisions allocated to Gough's Mobile Army were from the New Army. The 12th (Eastern) Division was one of them. It was, in fact, the senior of the four and was located the closest to the centre of the proposed breakthrough. Its three brigades were billeted in villages alongside the main road back to Amiens. The three cavalry divisions were located on the other side of that road. It must have been thrilling for the Eastern Counties soldiers to see the cavalrymen and to relish the opportunity of taking part in such a potentially decisive action.

There can be no doubt of what the division's role was intended to be at this preparatory stage. The Divisional History refers to the Martinpuich area being the division's main objective. I once talked with a man who had been a sergeant in one of the division's two Royal Fusilier battalions. He told me that their training for this battle was to force march straight up the Bapaume road and secure a hill known as the Butte de Warlencourt. Martinpuich and the Butte de Warlencourt were four and six miles behind the German front lines.

It has to be stated that these ambitious plans became subject to some revision in the last few days before the attack opened on 1st July. There is no need to go into this in detail here. We should move on to a description of the actual outcome.

The Dashing of Hope

Some of the high command had expressed reservations as to whether the 'Gough's Mobile Army' breakthrough plan would be achieved, but the actual outcome of the opening of the offensive was a disaster beyond anyone's expectation.

There cannot be many people who do not know what happened on that first day of The Battle of the Somme. The whole of the centre and north of the Fourth Army's attack was beaten off by the Germans with the exception of two small, widely separated, footholds in the German line - both quite useless as a foundation for exploitation. Only on the British right and on the French sectors was there any success. The British casualties were enormous - nearly 20,000 men killed and 40,000 wounded. It remains the bloodiest day in the history of the British Army. (A description of it was the subject of my first book. At the time I thought it would be only book!)

The heaviest casualties were suffered by the two divisions attacking astride the Bapaume Road - the main axis of what should have been the eventual advance of Gough's Reserve Army. This was clearly not now going to take place. A swift decision was made. The two battered divisions of the first day - the 8th Regulars and the 34th New Army - were to be withdrawn that night and replaced by the two nearest available fresh divisions; these would recommence the attack the next morning. One of the new divisions was the 19th (Western) from the Fourth Army's own reserve; the other was the 12th (Eastern) from the Reserve Army.

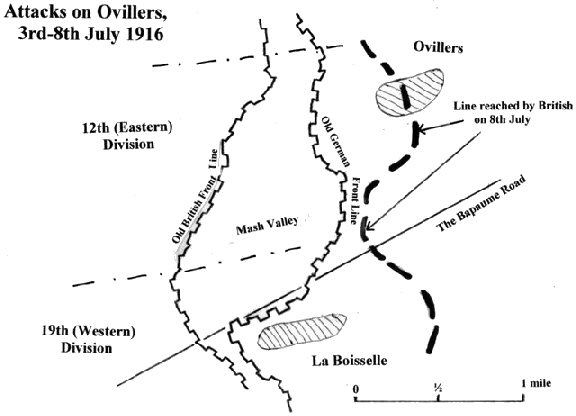

The German defences were anchored on two villages whose ruins made them into near impregnable fortresses. These were La Boisselle, situated just off the main road, and Ovillers to the north, across what the British soldiers called Mash Valley. (A twin valley on the south of the main road was Sausage Valley.) The two villages were close to the German front line but the intervening No Man's Land in Mash Valley was 800 yards deep because the Germans had positioned their front line on the high ground at the head of the valley. The combination of villages and the wide No Man's Land in Mash Valley made for a particularly strong German defensive sector.

The 19th (Western) Division commenced their attack on the morning of 2nd July and, by hard fighting, eventually captured the village. The details of this are not relevant to our story but the later decision by the division to erect their main permanent Western Front memorial just in front of the village church is important.

The 12th (Eastern) Division spent the night of 1st July taking over the trenches previously held by the 8th Division, but conditions were so chaotic that the attack planned for the next morning had to be postponed by one day. So it was that on the morning of 3rd July, instead of marching up the Bapaume Road to Martinpuich and the Butte de Warlencourt, the division was sucked into the grim battle of attrition into which the Battle of the Somme was developing.

It is not the purpose of this article to take you through the experiences of the 12th (Eastern) Division on the Somme in detail, only to show you how a memorial built at Ovillers is now in British Columbia, so what follows will be no more than a résumé of what happened.

The division made three separate frontal attacks on Ovillers in the course of five days. No more than a foothold in the ruins of the village was gained. The Germans, a high-quality Garde Fusilier regiment, resisted stubbornly on a line running through the village level with the church. The attackers never breached that line, never got past the church. The division's casualties numbered 4,643 men - 1,857 killed and missing, 2,708 wounded. Most of the missing were dead and would never have an identified grave; very few would have been taken prisoner.

The 12th Division was withdrawn on the night of 8th July. Ovillers never was taken by frontal attack; it only fell when it was later outflanked from the right and the remnants of the German garrison surrendered.

The division was only allowed a brief rest before coming back to the fighting again. This time it was in the area around Pozières, only a mile and half further forward from Ovillers. Another casualties list - nearly 3,000 - was incurred in the next two weeks. Then, after a spell in more peaceful trenches on the Arras front, the division was back to the Somme again in October for its third round of attacks near Guedecourt, close to where the Somme battle spluttered to a halt in mid-November.

The final British advance up the Bapaume road was, ironically, only to the foot of the Butte de Warlencourt - after 140 days of fighting and over 400,000 British casualties.

The official 12th (Eastern) Division's share of this total was 10,923 men. Its experiences had probably been no more than typical of an average British infantry division taking part in the Battle of the Somme in 1916. But these losses, together with those suffered at Loos in 1915, meant that the early-war volunteer character of the division, particularly of its infantry, had mostly been lost. The casualties were now mostly being replaced with conscripts.

The Ovillers Cross

The 12th (Eastern) Division's next battle was at Arras in 1917. The division was allocated a place in the front line of the attack on the first day - April 9th. Easter Monday. Its attack was a complete success, advancing to 4,000 yards at a cost of less than 600 men killed. A second Victoria Cross for the division was awarded, to Sergeant Harry Cator, of the 6th East Surreys. He was a native of Drayton, near Norwich, who had volunteered for the New Army in September 1914 the day after his marriage. He was badly wounded a few days after winning his VC but survived.

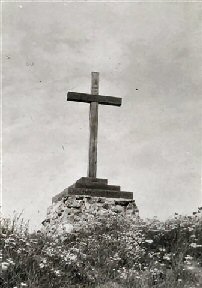

The Germans had retired from the Somme battlefield to their new Hindenburg Line earlier in 1917 and Ovillers had now become a safe backwater area. At some time that summer the 12th (Eastern) Division's Royal Engineers erected a memorial cross near the ruins of Ovillers church.

The oak timbers may have come from the ruins of Ovillers or they may have been purchased from an area further to the rear. A prominent split in the main upright is visible in a photograph taken soon afterwards. The REs constructed a firm platform of stone undoubtedly collected from the local ruins. The whole edifice was of fine quality.

|

The following inscriptions were painted on the cross and on the

base:

IN GRANT THEM O LORD ETERNAL REST |

Wild flowers rapidly established themselves and bloomed in the surrounding ground. It is possible that the 19th (Western) Division, which had shared in the attack on the German line on this sector in 1916, erected a similar memorial next to the ruins of the church in La Boisselle.

The war continued. The 12th (Eastern) Division remained on the Western Front through to the end in November 1918. It took part in almost every major battle. The only large one it missed was Third Ypres - the 'Passchendaele Battle' fought in the mud of Belgium in late summer and autumn of 1917. The division always performed well. Four more Victoria Crosses were won. The division had a second major success in September 1918, during the so-called 'Advance to Victory', when in two days of hard fighting it captured Epéhy, described in the Divisional History as 'a very strong outpost of the Hindenburg Line'.

I have two different figures for the 12th Division's total war casualties - 41,363 and 48,140. Both figures are above the average for the thirty Kitchener New Army divisions. Whichever is correct, it means that the division had a personnel turnover of 200 per cent during its three and a half years of service on the British Army's most important war front. The infantry battalions probably suffered 300 per cent casualties. There would not have been many of the 1914 volunteers remaining, particularly in the rifle companies, but some trace of the original spirit of the New Army must have endured.

Demobilisation commenced after the Armistice. The 12th (Eastern) Division was officially disbanded at Dunkirk on June 27th, 1919.

The Post-War Memorials

Many of the officers of the 12th (Eastern) Division remained in touch with each other after the war. This was a division that had served on one front for the whole of its active service and had been hardly touched by the reorganisations that sometimes took place in the British Expeditionary Force. It was decided that, despite the fact that the Ovillers Cross was still standing, there should be a more permanent memorial and that it should represent the casualties suffered in all of the battles in which the division had taken part. Major-General Scott, who had commanded the division for most of its active service, obviously made his views known.

Fifty-six British infantry divisions had fought on the Western Front in the First World War. In the early 1920s most but not all were deciding what to do about permanent memorials. Some decided to put all their resources into one main memorial. Some decided to have two, one on France and one in Belgium. Very little of the 12th Division's service had been in Belgium; there would be no memorial in that country. It can be assumed that the decision-making went as follows. The Ovillers Cross represented only one battle and that was at a place where, despite great effort and sacrifice, the division's attack had failed to capture its objective. The committee of former divisional officers - there must have been a committee - looked for a place where the division had carried out a successful attack.

Two places were considered - Wancourt on the 1917 Arras battlefield and Epéhy in the 1918 Advance to Victory. Perhaps because of indecision, perhaps because there were ample funds, it was decided to erect memorials at both places. And so it was done. Two identical fine stone memorials were erected at those places. They were dedicated on the same day in July 1921 in the presence of Major-General Scott, many ex-members of the division and the usual collection of notables that were present at dozens of such events at that period.

It is interesting to note that the 19th (Western) Division which attacked La Boisselle at the same time as the 12th (Eastern) Division was attacking Ovillers in July 1916, erected their permanent memorial by the church in La Boisselle. But, unlike the 12th Division, the 19th had succeeded in capturing their objective at that time.

What about the cross at Ovillers? The 12th Divisional History, published in 1923, describes the unveiling of the memorials at Wancourt and Epéhy two years earlier and adds that the cross at Ovillers was still standing at that time, 'a memorial to the brave men who fell in the great fight in July 1916'. How did that wooden cross reach British Columbia?

Captain F. T. Lee-Norman

The Royal Engineers - the REs - element in a First World War infantry division was a considerable one. There were three Field Companies and a Signal Company (this last was before the days of the Royal Signals). These units were under the command of the division's 'Commander Royal Engineers', always know as the 'CRE' and carrying the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. In addition to his RE units, he was also responsible for the employment of the division's Pioneer Battalion.

The CRE was probably responsible for more men in a division than any other officer of his rank. He needed a good staff. The principal member of that staff was his Adjutant - a Captain. Anyone who has ever served as a soldier knows that the Adjutant is the key officer of any unit, the officer who not only sees that his commander's orders are put into practice but also speaks for the commander when that officer is temporarily absent.

|

The Adjutant to the 12th (Eastern) Division's CRE for most of the

war was Captain Francis Thomas Lee-Norman.

In 1914 Tom Lee-Norman was a twenty-seven-years-old unmarried engineer working in Argentina. Soon after the outbreak of war he decided to return to England and join the Army. Optimistically, he purchased a return steamer ticket. He enlisted in the Royal Engineers and his qualifications ensured that he was commissioned in January 1915 and, as far as is known, was immediately posted to the newly formed 12th (Eastern) Division and was eventually promoted to Captain and became Adjutant to the CRE. |

He received a Mention in Dispatches in June 1916, before the Somme battle, so he must have performed well in his duties during the period that the division was in action in the Loos area. In January 1917 he was awarded the Military Cross. Because this was recorded in the New Year's Honours List, it probably reflected further good work over a long period rather than an individual act of gallantry. The Adjutant of a unit did not have much opportunity for such acts.

He served with the division right to the end, only returning to England a few days before the division was disbanded in 1919. His next posting was to Ireland, but he was soon demobilised and returned to his previous occupation in Argentina. It is not known whether the return steamer ticket he had purchased in 1914 was still valid.

His four years of war service had been one of steady, conscientious duty, almost all with the 12th (Eastern) Division. His future wife, Winifred Tonge, travelled to Argentina to marry Tom in 1920. They soon returned to England and lived in Little Court, an Edwardian country house near Dorchester, Dorset, his wife's family home. Their son, Alexander, was born in December 1921 and two daughters later completed the family. Little Court would represent the first stage of the move of the Ovillers Cross to British Columbia.

The Ovillers Cross Leaves France

| Tom Lee-Norman remained in touch with his wartime comrades. A photograph

shows him present at a large dinner reunion of ex-officers of the division

at a London hotel. The subject was soon raised as to what action should be

taken about the wooden cross that had been erected at Ovillers in 1917. The

next part of the story must be partially based on speculation.

It is likely that the people of Ovillers wished the cross to be removed because it was obstructing the post-war reconstruction of their village. Lee-Norman, as Adjutant to the wartime CRE, had almost certainly been involved in the erection of the cross. |

|

|

What is known is that the memorial - still in good condition - was dismantled and transported to England and brought to Little Court in 1925. Perhaps that was intended as a temporary move pending the finding of a permanent home in the Eastern Counties whose men had formed the division in 1914. It could have an entirely appropriate home in any of the cathedrals or regimental museums from Norwich round through the arc of Eastern Counties to Canterbury. But nothing happened. Perhaps Tom Lee-Norman had wanted to keep the cross at his home at Little Court. Whatever the reason, there it was destined to remain for nearly three-quarters of a century! It was re-erected in a corner of what was called the Billiard Room, though this was mainly used as the children's play room. The cross was plastered to the wall and usually covered by a curtain. For the children, daughter Elizabeth says, 'it was just part of the family furniture; we had no particular reverence for it'. |

The Second World War brought mixed fortunes to the Lee-Norman family. As with so many families in a certain age group, the next generation went off to serve in the forces as their fathers had in 1914. None of Tom Lee-Norman's children followed him into the Army. The daughters both joined the WRNS (Women's Royal Naval Service); Elizabeth became a driver attached to the Admiralty in London; her sister, Anne, was a 'boats crew' Wren at Portsmouth. Their brother Alex joined the Royal Air Force; he was selected for pilot training and sent to what was then Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, under the Empire Air Training Scheme. Sadly, he died in a flying accident in 1942, aged only nineteen. (His grave is in the Athlone Cemetery at Bulawayo, one of 133 British graves there, mostly of 'Pilots under Training' or of 'Pilot Instructors'.)

Wren Lee-Norman

Tom Lee-Norman also did not survive the war. He died of cancer in 1941, aged only fifty-four.

The Cross Finds A Permanent Home

In 1956 Elizabeth Lee-Norman married John Huxtable, a young man also from Dorset who had served in the Royal Navy in the latter part of the war and later emigrated to Canada and joined the Royal Canadian Navy. After his retirement they remained in their home city of Halifax, Nova Scotia. The second step in the eventual movement of the Ovillers Cross to Canada had been established.

John Huxtable died in March 2007. Elizabeth still lives in Halifax but spends part of each year in England.

Antonia was one of Mrs Huxtable's two daughters. She moved to Germany where she continued her music studies at Freiburg and Munich. It was here in 1987 that she met her future husband, Albert Mahon, a fellow Canadian who was travelling around the world at that time. They eventually settled in Penticton, in the Okanagan Valley in mid-British Columbia, nearly 3,000 miles further westward across Canada.

Back in England, in the late 1990s, the Huxtable family were starting to think about selling Little Court. It was thought that having a large cross in the house might put off potential buyers. A retired General, a cousin of Elizabeth Huxtable, tried to find a recipient for the cross in England but was unsuccessful.

Back again in Canada, Antonia Mahon and family went on a day trip to the town of Kelowna, about forty miles from Penticton, to visit her parents-in-law. It was a fine day. A table had been set up in the Orchard Park Shopping Centre at which two local ex-servicemen - Don Appleton and Don Mann - were appealing for support, funds and artefacts for a proposed Military Museum. Antonia asked, 'Would you like a large wooden memorial cross from the First World War that once stood on the Somme battlefield?' 'Yes, please'. 'Well, it's in England'.

That was in 1997. For the Huxtable family who were trying to sell Little Court and find a suitable home for the cross 'it was the solution to a problem'. The cross was crated and shipped across the Atlantic by Pickfords in 1998 ; it was delivered to Antonia Mahon at Penticton. Its eventual transfer to the museum at Kelowna as a gift in perpetuity from Elizabeth Huxtable gave the family 'tremendous peace of mind'. Mrs Huxtable also donated her father's wartime steel helmet with the 12th (Eastern) Division's Ace of Spades divisional sign painted on it, his miniature medals, and as many photographs and documents as were available. A small inscription plate was added to the cross to record the gift, coupled with Captain Lee-Norman's name and the sentiment that the cross should also be regarded in his 'everlasting memory' - a fitting tribute to the officer who had fought at Ovillers in 1916, had almost certainly been involved in the construction of the cross there in 1917 and who, with his family, had cared for it as a tribute to the men of the division for so many years.

(Little Court was eventually sold in 2002. It still retains its Edwardian charm and is now a Bed and Breakfast Hotel. The Billiard Room in which the Ovillers Cross stood for more than seventy years became the Guest Lounge.)

|

|

After some months in storage in the basement of the Laurel Building in Kelowna, the cross came to form the centrepiece of The Okanagen Military Museum when it was opened in 1999 in the Kelowna Memorial Arena. Antonia Mahon, Tom Lee-Norman's granddaughter, and her family were present. They and the cross were the source of much interest by the media representatives present.

And that is how a memorial to the men from the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk, Northamptonshire, Essex, Middlesex, the City of London (two Royal Fusiliers battalions), Berkshire, Surrey, Sussex and Kent who were the first to volunteer for Kitchener's New Army in England in 1914 and who died attempting to break the German line on the Somme in 1916 came to a town in British Columbia.

Here are some further photographs which illustrate the story of the Memorial Cross. Click on any photograph to see a larger version with explanatory details.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note to Visitors. Opening times at the Okanagan Military Museum at the time this article is being written - November 2007 - are:

Summer, Tuesday to Saturday, 10am to 4pm.

Winter, Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, 10am to 4pm.

Postal address is 1424 Ellis Street, KELOWNA, BC; Canada V1Y 2A5

Website: www.okmilmuseum.ca.

Email: militarymuseum@kelownamuseums.ca

Admission is by Donation. Please be generous (author's words).

Acknowledgements: Mrs Elizabeth Huxtable, Halifax, Nova Scotia, and Mrs Antonia Mahon, Penticton, British Columbia. Keith Boehmer, Okanagen Military Museum. Mary Middlebrook; Amanda Bowley, Little Court; Teddy Colligan, Ulster Tower, Thiepval, Somme - all for photographic help. Margaret and Alan Stansfield, Elland, Yorkshire, and Dick Rayner, Spixworth, Norwich - for research help.

Martin Middlebrook, Tewkesbury, England. 2007.

Martin Middlebrook has written the following First World War books: The First Day on the Somme, The Kaiser's Battle, The Middlebrook Guide to the Somme Battlefields (formerly The Somme Battlefields), Your Country Needs You, The North Midland Territorials Go To War.

Second World War: The Bomber Command War Diaries (with the late Chris Everitt), The Sinking of the Prince of Wales and the Repulse (with Patrick Mahoney), Convoy, The Battle of Hamburg, The Schweinfurt-Regensburg Mission, The Peenemünde Raid, The Berlin Raids, The Nuremberg Raid, Arnhem 1944.

The 1982 South Atlantic War: The Falklands War, The Argentine Fight for the Falklands.

![]()

Copyright © Martin Middlebrook,

December, 2007.

Copyright © Martin Middlebrook,

December, 2007.

Return to the Hellfire Corner Contents Section